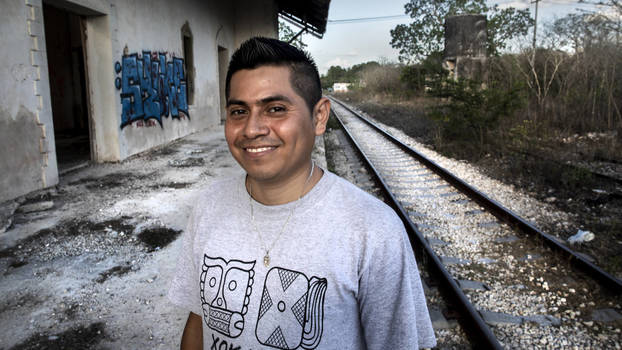

“How does the government see us? Here, peddling our handcrafts at the train stations? (…) There are other options for us, and the Mayan Train is not an alternative.” −Gregorio Haue, Múuch' Xíinbal Assembly of Mayan Territory Defenders. Photo: Maya Goded Colichio

The current President of Mexico, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, initially described his administration as a left-wing government. Later, around the time he announced the construction of the Tren Maya (“Mayan Train”), he began to define it as a liberal government. The Mayan Train is one of his administration’s main infrastructure projects: the building of eighteen railway stations with a 1,500-kilometre trajectory connecting five different states in southern Mexico, thus linking cities like Cancún, Playa del Carmen, and Palenque, among others. The megaproject’s stated aim is to offer “social well-being to the inhabitants of the Mayan zone” by connecting “the region’s main tourist cities and circuits in order to integrate territories with great natural and cultural wealth into the region’s tourist, environmental, and social development”. Since the announcement, many Mayan communities and organizations—along with scientists, anthropologists, and environmental advocates—have expressed opposition to the megaproject, claiming it will harm the environment and modify the life and culture of the Mayan peoples dwelling in the region.

Gloria Muñoz Ramírez has worked as a journalist for 30 years, gathering experiences in indigenous communities and social movements around the world, while teaching at university and community journalism courses. She is the founder and editor of Desinformémonos, a digital communication space, a columnist for the newspaper La Jornada, and co-editor of the Ojarasca supplement of the same newspaper, dedicated to the indigenous movement and literature. Maya Goded Colichio is a Mexican photographer and documentary filmmaker. Her work focuses on femininity, motherhood, gender violence, marginality, inequality, transgression, sexuality, the body, morality, myths, indigenous communities, and the defense of territory. She is the author of the books Guerrero Negro (1994), Plaza de la Soledad (2006) and Good Girls (2006), as well as the documentary Plaza de la soledad (2016).

On the one hand, the federal government’s proposal aims to generate employment, stimulate the region’s economy, and develop infrastructure with basic services in order to improve overall quality of life. It should be noted, however, that private companies have already invested in large-scale projects in this region for years, mostly photovoltaic cells, agroindustry, and wind farms. For these megaprojects, the Mayan Train would represent an opportunity for them to connect. Yet the companies promoting these activities have already significantly impacted the region. Forests, for instance, are being cut down to make way for industrial farms owned primarily by Mennonites, who in turn cultivate genetically modified soybeans produced by Monsanto, acquired by Bayer in 2018. As they extend their farmable land, they poison local water, air, and land with toxic agrochemicals, and destroy the organic beekeeping projects in Mayan communities that have sustained the economy of many families through selling honey, a large portion of which is exported to Germany.

Another project, by contrast, aims to conserve “the little we have left, our mountains, our livelihood, our organization, our language, and our culture,” as Pedro Uc, the Mayan poet and activist from the Múuch’ Xíinbal Assembly of Mayan Territory Defenders, puts it. The construction of the Mayan Train will mean evicting the region’s original inhabitants, as Benito Caamal from the Muuch Kanan l’inaj Seed Collective states: “I wouldn’t like to abandon my land or live close to the rail line. I won’t leave my land because we grew up here. Our elders are here. Our parents are here. The government thinks that we all want to move over there, but we are not planning to leave.”

“The debate is not… whether to say yes or no to the train, but rather how we view our lives.” −Ángel Sulub Santos from the U kúuchil k Ch'i'ibalo'on -Raxalaj Mayab' Community Center. Photo: Maya Goded Colichio

In Mayan country, he continues, “water is also a problem. There’s a brewery in the eastern part of the city of Mérida that uses up the community’s water, which is why the wells are drying up. The brewery is appropriating all the water and the communities that are left without water are deeply concerned. … The area known as Los Chenes … depends on water flowing in underground rivers. We are denouncing that the excessive extraction of water as an attack against our territory. Public policies are promoting rice fields in an area that is unsuitable for this. It is very hot here and all the water extracted from the subsoil is exposed to ongoing evaporation.”

All of the aforementioned is taking place without any environmental impact studies and without genuine consultations with the affected indigenous peoples, as stipulated by International Labor Organization (ILO) Convention 169. Indigenous organizations themselves are opposed to the project, beginning with the name the government has given it: “Who allowed them to appropriate the Mayan identity?”

“The Mayan Train will be the first regionally planned tourist circuit to respond to new expectations of increasingly demanding tourists,” Andrés Manuel López Obrador declared via tweet. An increase in the number of tourists is not so widely accepted by the local population: “a great number of local youths are training in technical degrees such as hospitality, gastronomy, and bartending to take jobs in the tourist zone. With these studies, they seek employment in these fields to provide for their families, but this actually leads to an impoverishment of our people, creating unmet needs, and economic scarcity in our communities. This is something our ancestors did not suffer in the past,” claims Ángel Sulub Santos from the U kúuchil k Ch'i'ibalo'on -Raxalaj Mayab' Community Center.

“The President has an approach to development that does not coincide with that of the local inhabitants,” notes Heber Uc Rivero, a member of Bacalar’s Indigenous Council. “This megaproject has been set forth as community development, a development that does not emerge from our way of thinking, but is rather that which was promoted from Cancún to Playa del Carmen, where the level of violence has increased and drug lords fight over the territory.”

The government has remained silent in the face of arguments put forth by the Mayans against project. The inhabitants of southern Mexico continue to ask, “Who is this progress meant for?”