Last year, the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung’s political educational outreach focused on the past 30 years of German unity and East Germans’ experiences of transformation. We sat down with RLS chairperson Dagmar Enkelmann to talk about the social challenges of German reunification and to hear her personal take on the situation.

Every year the federal government’s commissioner for East German affairs presents a report on the state of German unity. For the federal government, German unity is a success story. What’s your view on it?

The report is supposed to point out successes, problems, and trends. And the figures don’t exactly paint a picture of success. A stable East-West divide has long been documented. In 2019, for example, the new federal states’ [i.e. former East Germany] economic power was just 79.1 percent of the overall German average and disposable household income in East Germany had reached 88.3 percent. Workers in former eastern states continue to earn considerably less than they would with the same qualifications in the former west. According to a study conducted by the Hans Böckler Foundation, workers of the same gender with comparable experience in the same profession are paid almost 17 percent less in the east. But it isn’t only about inequality in terms of infrastructure and life opportunities—it’s also about different values, attitudes, lifestyles, and life goals. An honest reappraisal of the shortcomings of German reunification and new ideas for future development are long overdue.

The federal government’s commissioner for East German affairs has lamented East Germans’ “major democratic deficits”, which he blames on their having been “socialized in a dictatorship”…

For 30 years now, I’ve been hearing about how the East German government is to blame for the East’s problems. I think it’s about time that the federal government began reflecting on its own failures in this regard. Let us recall the first experiences and disappointments that West German democracy had in store for East Germans in the early 90s: their personal histories and careers were devalued and they faced mass unemployment, while at the same time West German elites assumed control of key political and economic leadership positions. Last May, Wolfgang Engler wrote a piece for the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung on “The East Germans and Democracy”. I quote: “The habitual exclusion of post-reunification history from the examination of the causes of the so-called ‘rightward lean’ of the inhabitants of the former East is guided by vested interests. It is ideology, plain and simple.” I couldn’t have summarized it any better myself.

30 years of German unity and experiences of transformation—a subject only relevant to East Germany?

That was our fear at first. But it isn’t the case. Our travelling exhibition Schicksal Treuhand: Treuhand-Schicksale is providing a space for people to tell their own stories. It has certainly touched a nerve among East Germans. The exhibition opened in August 2019 in Erfurt, and since then has been making its way across Germany. It has generated considerable interest in East German federal states, but the 19 locations that have hosted the exhibition also include places like Heidelberg, Braunschweig, Fürstenfeldbruck, and Erlangen. Visitors often write personal comments in the guestbook, such as: “These two West Germans were shocked—we didn’t know it was like that. Sad, and very informative.” That one really gave me cause for thought. This side of the story seems to have been left out of the social discussion about reunification.

What makes the story of the Treuhandanstalt (the agency responsible for privatizing formerly state-owned East German enterprises) so explosive?

Entire generations of East German citizens have felt the consequences of Treuhand’s privatization policies. Through no fault of their own, they lost their jobs and thus their entire livelihoods. At the same time, their employment history was invalidated. For a long time, no one spoke about this period and the effect it had on their lives. The feeling of being a second-class citizen kept a lot of people from speaking up. That’s why it has been one of the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung’s main priorities to create a space for open discussion around this issue. It’s important for younger and future generations to get an East German perspective on the effects of the Treuhandanstalt, told by those who were directly affected by it. We want to combine a personal look back at their parents’ and grandparents’ generation with a broader discussion about the political reappraisal of Treuhand policies. Its consequences are still clearly visible in East Germany today: a compartmentalized economy, insufficient technological resources for sustainable development, poverty among the elderly… A reappraisal of the path to German unity is urgently necessary, as is a vision for future development. It’s been 30 years since East Germany joined the federal republic, and the promise of equal social and democratic participation remains unfulfilled. We have to think about social alternatives.

What other related projects has the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung supported?

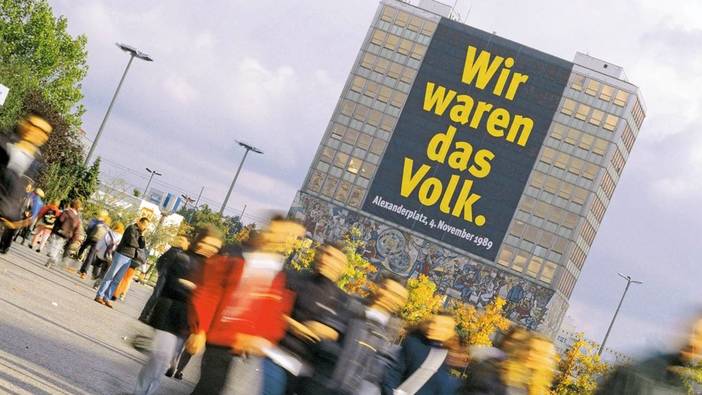

In an online timeline, we told a “different story” about the events leading up to German reunification. It focused on the period between 1989–1990, when everything seemed possible. It highlighted the atmosphere of change and optimism about the future and people’s hopes and dreams, but also examined the defeats. The local elections of 7 May 1989 were the initial spark that instigated the implosion of the GDR. On a personal level, it was a surprising experience to re-live this single year by tracing its most striking events. We’ve published numerous contributions to the discussion on our website, where you can read it all in an online portfolio. In publications we’ve tried to present the experiences and events of this period from a new perspective: for example, the turbulent first year of the Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS), the United Left initiative, and the repression of leftists and emancipatory movements that occurred in East Germany. But we’ve also supported the publication of Gerd Dietrich’s three-volume cultural history of the GDR, and Dietz Verlag’s release of the tape transcripts which document the expulsion of party members from the politburo in 1990. In this way we’ve recovered important experiences and events from this time which otherwise would have remained forgotten.

Forgotten is a good key word here. What was the path to German unity like for you personally?

I had my third child in 1989 and was on maternity leave. I followed the political developments. Initially I was involved in round-table discussions for the Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS) in Bernau and shortly thereafter I was elected to the Volkskammer (the East German parliament). I can still vividly remember the day of the Volkskammer’s constituent session at the Palace of the Republic on 5 April 1990. The parking lot out front was full of cars by different manufacturers that I’d never seen before. Among them was my sky-blue Trabant. It was my first Volkskammer meeting and everything was new for me and many of my party colleagues. The other party representatives had already been assigned “West German development aid workers”. Nevertheless, there was a different kind of cooperation back then, compared to what occurred later in the Bundestag. We had all been socialized in the GDR. Relations were cordial, despite our different backgrounds. Later, in Bonn, other colleagues from the new federal states and I initially organized an informal “East German roundtable” to discuss special tasks and problems post-reunification. When the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) leadership learned about it, they immediately prohibited their members from attending.

Your time in the Volkskammer was brief. On 23 August 1990 the Volkskammer voted to accede to the Federal Republic of Germany in accordance with Article 23 of the West German Basic Law…

The PDS faction voted unanimously against it. We felt that important economic and social issues hadn’t yet been resolved. It was easy to see that the German reunification might not be carried out on equal terms. On 2 October there was a special session at the GDR State Council Building, followed by a reunification ceremony in the concert hall at Gendarmenmarkt square in Berlin, which I didn’t attend. I went to my constituency office in Bernau, to sit and talk with like-minded people. I remember that André Stahl, the current mayor of Bernau, was there. We all agreed that there had to be socialists in the new Germany. Around midnight the national anthems of the GDR and Germany rang out.

What were the first days like in Bonn?

There was a special session at the Bundestag on 3 October, and then the normal week of sessions began. It was an odd feeling. The plenary assembly met in the old waterworks building. We were assigned offices in the former kindergarten at Tulpenfeld. The other Volkskammer representatives were incorporated into their respective parties; we were separate from day one. The first thing I noticed was that there wasn’t anyone there to count votes, like there had been in the Volkskammer. Shortly thereafter it became clear to me why. A block voting system was in place. For example, on Thursdays there was always “voting without a debate”. The printed document that was to be voted on would be called up, with no mention of its title or theme. We had arrived only the day before and didn’t have the slightest idea. At first, we abstained from voting. But then it just became too pointless, and for the first time we walked out of the Bundestag as a group. Eventually we were able to get them to at least name the title of each bill. We also had to get used to the committee work and other appointments that took place during the plenary sessions. The rows emptied out quickly, at first only the East German delegates remained in their seats…

The first Germany-wide elections took place on 2 December 1990. A special electoral law created separate electoral regions for the East and West. If a party exceeded five percent in an electoral area it would enter the Bundestag. That was the case with the PDS/Linke Liste…

We were able to gain 17 mandates, which was a surprise, to be honest. Parliamentary operations in Bonn were a major adjustment for us and our staff. For the established parties we were an imposition. But not only were our political approaches unconventional—we were also extremely polite. The Bundestag administrative staff appreciated that we said “please” and “thank you” and helped us from day one. And we were a “colourful crew” both figuratively and literally. The PDS brought colour into the parliament, with the young women among us in particular often wearing red.

That certainly didn’t escape the notice of the journalists who elected you “Miss Bundestag”…

I found that quite upsetting, at first. I felt that I had been reduced to my appearance and trivialized as a politician. But Gregor [Gysi—Ed.] immediately recognized it as an opportunity to gain more publicity for our political work. I was invited onto talk shows and received frequent interview requests, and it enabled me to draw attention to our political message. For years, I was asked about that again and again in interviews.

“Germany—a united fatherland?” On 17 September 2020 the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung co-hosted a podium discussion on this theme together with Die Linke’s parliamentary group. How do you assess the state of German unity today?

German unity is an ongoing process. While it did open up new opportunities and freedoms for citizens of the GDR, not everyone was able to take advantage of them. A great many injustices and inequalities—economic, cultural, and social—persist to this day. If after three decades of German unity 57 percent of East Germans still feel like second-class citizens—as a Forsa survey completed for the Federal Press Office suggests—then something has clearly gone terribly wrong.

Translated by Caroline Schmidt & Ryan Eyers for Gegensatz Translation Collective.