After more than five years of authoritarian rule and rent-seeking, “gangster”-type neoliberal economic policies, the strongman rule of Rodrigo “Digong” Duterte has begun to unravel as the Philippines gears up for the national elections in May 2022.

Realignments of social and political forces are beginning to reconfigure the political landscape amidst the continuing COVID-19 pandemic. Progressive and traditional social forces are drawing their political lines as the mounting opposition against Duterte expands. IRGAC fellow Verna Dinah Q. Vaijar spoke with Joel Rocamora, a renowned author, political analyst, and progressive governance practitioner, to better understand Duterte’s authoritarian rise, the reconfiguration of the elite and other social classes, the political/ideological debates within the Philippine Left movement, and the political realignments in the run-up to the Philippine presidential elections in 2022.

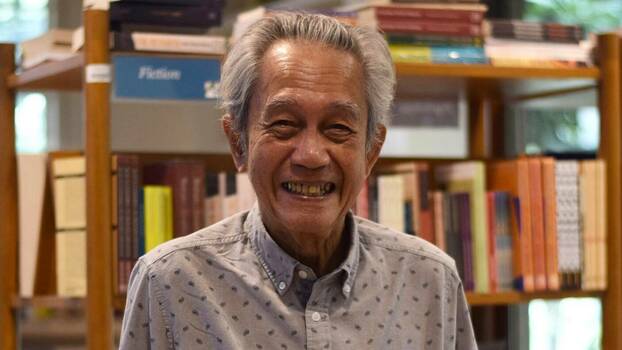

Joel Rocamora was formerly a member of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP), and later headed the Institute for Popular Democracy. His publications include Breaking Through: The Struggle within the Communist Party of the Philippines (Anvil, 1994) and Impossible Is Not So Easy (Bughaw, 2020).

Verna Dinah Q. Vaijar is a fellow at the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation’s International Research Group on Authoritarianism and Counter-Strategies, where this interview first appeared.

VV: How do you analyse the rise of authoritarianism under President Rodrigo Duterte?

JR: If I have to choose a theory that would connect what is happening in the Philippines with the rest of the world, I suppose I would use authoritarian populism. It is clear that President Rodrigo Duterte is authoritarian. Like what he is doing to the media, putting people like Senator Leila De Lima in jail, etc.

I think it is still useful to use the word “populist” simply because Duterte has succeeded. The key idea about “populism” is to be able to persuade a large enough number of people that they are “the people” and he is the leader. By its very nature, it undercuts institutions of representation. Although Duterte won an election, his power emanates from “popularity”, is in a way separate from institutions of representation as they exist.

On the other hand, if you link him to what I termed as “demobilizing populist”, there are populists who succeeded in building mass organizations—even Modi in India. But Duterte failed on this. Nevertheless, his anti-elite and anti-establishment image succeeded even though his economic policies are supportive of the continuation of the elite and neoliberal in nature.

For me, I focus my analysis on Duterte’s personality. Many of the things he has done reflect specific aspects of his personality. I describe him in Visayan[1] term as hambogerong[2] bugoy[3]. It’s like he never grew up from being a teenage bugoy.[4] The sociology of the term bugoy is quite specific and Duterte is conscious of this and identifies himself as such. Also, his role as hambogerong bugoy is because while he was growing up, he played a leading role among the street hooligans due to his upper-class status. His father was a cabinet minister, and he could even afford to study how to fly an airplane.

Digong[5] is bugoy, a hooligan, but a cut above the rest because he is rich, he is not “lumpen”. Many aspects of Digong’s personality points to the fact that he acts like he never grew up, he remained a teenage hambogerong bugoy.

Is this term specific only to the Philippine context?

Yes, it also relates to the former president, Joseph “Erap” Estrada.[6] His family is also from the upper-middle class, but he preferred the company of the bugoys or kanto boys (street kids). But if you link it to Duterte’s success in getting elected, it has a lot to do with the specifics in the 2016 elections. His anti-establishment image worked perfectly against Mar Roxas[7] because who could be more “establishment” than a Mar Roxas whose grandfather was a former Philippine president, whose father was Senate president, who owned the whole of Cubao,[8] and studied at Wharton in the US?

I like Mar Roxas for president, because when we were in the cabinet together, I had a lot of interactions with him. He certainly would have made a lot better as a president, but he really lost to the “anti-establishment” line. Interestingly for Leni Robredo, who won as vice-president, this did not work because Leni’s image is probinsiyana,[9] and at best middle-class—unlike the ultra-upper-class image of Mar Roxas.

How would you link this to the global crisis of (neo-)liberal democracy?

Neoliberalism worsened a pre-existing situation in the Philippines, dating back to colonial days, which means, using the people and resources, and those you don’t need, you let them fend for themselves. The period of Pres. Benigno “Noynoy” Aquino (2010–2016) was a period of rapid economic growth. As you pointed out in your paper, the substantial support for Duterte from the upper-middle class, and those of the “new” middle class, that if not for rapid economic growth, the Duterte presidential win would not have happened.

We have a situation that there has been a long-standing division between the upper class and the rest of the population. What was new during the time Duterte got elected? That a new middle class of people emerged who benefited from strong economic growth, and then you have all the people below them who can see the possibility of improving their lives but frustrated that they could not. In a sense, what the new upper middle class did was to provide the poor with a new source of frustration.

When you bring in Gramsci, I agree that you use “hegemony”. It’s just that it is not active hegemony, there is an element of hegemony which is hegemonic in the upper class, but below (lower class) there is an opening for people like Duterte who challenge that hegemony. I would prefer to still use the term populist, as you have talked in your essay about authoritarian populism.

You led an institution called the Institute for Popular Democracy in the Philippines. How do you use the concept “popular” in this instance? Is the concept similar to the concept in authoritarian populism?

The term “popular” in popular democracy come from the Latino expression, popular, referring to the poor and the oppressed. The Institute for Popular Democracy came out from the national democratic movement, as it started fraying in the early- to mid-1980s. Three specific leading party members—Boy Morales (deceased), Isagani Serrano (deceased), and Ed dela Torre—were the source of popular democracy. An effort was made to generate a mass movement called “popdem”, but it never really succeeded. It relatively succeeded during the time of Boy Morales through his network of NGOs, but even that has weakened.

How would you analyse the current realignments of social forces in the Philippines in relation to the upcoming national elections on 2022?

I would not be so sure how the top of the elite, are going to position themselves in the coming elections. But I would think differently about the economic elite that were hit by Duterte, such as the Lopezes who owns the ABS-CBN network that was shutdown, the Zobel-Ayalas[10] and the Pangilinans, who Duterte attacked due to their water concessions, and even Lucio Tan, a Filipino-Chinese tycoon, was not spared by Duterte. I bet these guys will keep their heads low and not openly support Duterte’s opposition, specifically Leni Robredo (the vice-president),[11] but quietly provides resources. When the time comes, by February next year, the support of this very top of the elite will go towards the candidate of the opposition, and I suspect it will be Leni Robredo.

During the time of Pres. Noynoy Aquino, I presented an article I wrote at a conference of political scientists. I argued that the anti-rent-seeking policies of the Aquino government may have something to do with the modernizing section of the business class, i.e., the Makati[12] business club types. The businesspeople who prefer rent-seeking than profit-making are in decline. But if you look at Digong’s administration, perhaps this is still not a reality, that the Makati business-club types, who do not depend on political connections to make money, may not yet be the dominant segment of the upper class.

The fact is that the Philippines is a capitalist country, a large part of the economy operates despite the government. Capitalist economic activities continue but investments have gone down both in terms of domestic and international investment. And investment is influenced a lot by what people think of the government and how things are going to go in the future.

I am already part of the campaign machinery of Leni Robredo. In the past, I was a Marxist-Leninist, now I am only Leninist. My sense is that–although I have not the time nor the inclination to look for empirical data—a large part of the professional class such as journalists, academics, doctors, and lawyers support Leni. But the rank-and-file employees in offices—such as in Makati, where their situation is more precarious—if they see that there’s a movement towards Leni, I think they will follow. Just like during the yellow movement brought in by the Makati crowd.

But currently, there is no indication yet that this is happening. So, there is a division in the middle class—I sense that they are in a difficult situation due to the decline in the economy, unemployment has increased, that cannot but affect this segment of the middle class. It is difficult to say if they will be mobilized in the Leni campaign.

Crime, corruption, and traffic are middle-class issues that Duterte captured in his 2016 presidential campaign. He reached this segment of the population. Then there was the perception that Duterte is decisive, compared to the other candidates at that time. Secondly, we have an industrial class, but they don’t hold that much influence. Is it still the top elite that determine the economy? How do you analyse the Philippine elite?

As far as I see it, that is not the way the Lopezes or the Ayalas operate. If we look for political direction from that segment of the business class or upper class, we should look at the Makati Business Club, PMAP, etc.—these are the organizations to study. There are also the Filipino-Chinese business organizations but they are more rent-seekers in that group.

In the build-up of the elections, if you have read the recent news, there are reports that Duterte and his daughter are having a misunderstanding on who should run for President in the 2022 elections. Then there are questions whether Digong will run as vice-president, etc. I am not sure if this is just zarzuela.[13] What I know of the Duterte family is that the division within the family runs deep. Sara Duterte never really accepted that Duterte abandoned her mother. Sara refuses to have anything to do with Honeylet, Duterte’s current companion or replacement of her mother. My friends in Davao, including people in business, said that the whole period when Duterte ran Davao City, it was Paolo “Pulong” Duterte with the support of Bong Go who controlled rackets, such as smuggling in Davao City ports. This shady business became national when Duterte became president, such that they controlled the Bureau of Customs for a number of years. Also in rice smuggling, they controlled the National Food Authority (NFA) by putting Pulong’s men in the agency.

I suspect that the division and spat within the Duterte family is not zarzuela. My sense is that, maybe it’s a bit of wishful thinking, that it will be Bong Go who will be Digong’s candidate for president in the end and not Sara. Then Sara would be angry enough to go ahead and run for president to divide the Duterte vote. My sense is that Manny Pacquiao will run for president but he may agree to slide down as vice-president but the only one that he can run with is Leni as president. Most likely, he will run as president. If I could influence him, I would encourage him to do that so that he can take away Mindanao and Cebuano votes from Digong’s candidate. As for the Marcoses, Bongbong Marcos may slide down as vice-president with Sara as president if Digong will not push to run as vice president.

How do the political clans relate to this? I don’t think that many of them have made any firm decisions yet on who they will support in the 2022 elections. For now, if the dominant political party, PDP-Laban, tell them to sign and support Bong Go as president, they will sign but they will not toe the party line.

A specific example would be the Belmonte political clan in Quezon City. I am a friend of Kit Belmonte (Quezon City Councillor) and I sometimes talk to Joy Belmonte (Quezon City Mayor), the children of the patriarch Belmonte. In the end, they will decide towards who is the strongest candidate. The thing is, even outside that kind of political calculation, Kit and Joy Belmonte support VP Leni. During the 2016 elections, Joy Belmonte was active in campaigning for Leni as VP and Kit Belmonte is not only a member of the Liberal Party, but he is also ex-NPA (New Peoples’ Army), who is really coming from the Left movement. He was with the CPP for many years.

If we had better sociological studies, it would have been easier for to see which segment of the population will gravitate towards which candidate.

What about the other social forces such as the labour movement, which a big segment is supporting VP Leni for President? Would their support be relevant in the elections?

Yes. I think the broadest labour coalition now is NAGKAISA[14] and the dominant political tendency with this labour coalition is with Akbayan´.[15] Sentro, which is the Akbayan labour wing, is the dominant in Nagkaisa. As for the KMU,[16] I don’t think they have really recovered from the split of the Manila-Rizal party committee back in the 1990s. We know that the organized labour force, 90 percent of that are coming from the NCR plus the Laguna-Cavite regions. In that sense, the Nagkaisa is relevant and that is where the 1Sambayan[17] can help. The 1Sambayan creates a framework for the national democratic labour groups and the Akbayan labour groups to cooperate, which they constitute perhaps 70–80 percent of organized labour. They can play a significant role in the elections and I believe Nagkaisa will support Leni Robredo for president.

What can you say about the debates surrounding the Philippine Left concerning their differing analysis of Duterte’s form of authoritarianism?

With regards to Walden Bello’s argument that Duterte is a fascist, it’s a useful historical term in describing what happened in Western Europe, particularly Germany and Italy. The Communist Party of the Philippines also uses this term. But I don’t know how useful it is for describing the situation in the Philippines.

The strongest faction within the Philippine Left is still the national democratic groups. Jose Maria Sison[18] or “Joma” is right that you cannot be democratic and be Marxist-Leninist. Those of us, former Communist Party members who left the party, were part of the efforts to set up an alternative Communist Party. In the end, we concluded that it is a contradiction in terms – “democratic” and “Marxist-Leninist” at the same time.

But a major part of the “reaffirm” thrust of the CPP under Joma’s leadership, whose strategy was countryside surrounding the cities, and that all struggles are subordinate to the armed struggle, the last 15 or more years has not proven that those strategies worked. If you look at the national democratic movement today, the most successful ND efforts are not in the traditional strategies, i.e., armed struggles, or guerrilla zones framework of struggles. What has been successful are their party-list organizations that provide them with a lot of money and other resources. It is not their mass movements (i.e. Anakpawis, Gabriela, etc.) that provide the resources but these electoral parties.

So, what does that mean for the movement in the long run? This is where the Duterte government has failed, and the former Noynoy administration was not able to confront. I have a feeling, confirmed by a lot of discussions with friends within the movement, that the success of the national democratic parties and the fact that Joma is five years older than me (and I am 80 years old), means that the Joma wing of the party leadership plus those who control parties want a political settlement. It will probably split the party, but this is my sense.

What is your analysis of the Philippine military and police?

The military has maintained a significant degree of independence from Duterte. As for the police organization, I don’t think Duterte can control it nationally, at best he has to compete with mayors for control of the police. Because at the city and municipal level, the police organization is partially dependent or a significant portion of their resources on the local government executives particularly the city mayor. If the city mayor decides to support VP Leni or other candidates, Duterte cannot do anything

The military has gone out of its way to maintain good relations with VP Leni, who gets monthly security briefings from the top leadership of the military. Of course, I hate to admit this, there is the US influence due to the West Philippine Sea issue. The US wants to keep the military independent from Duterte and his Chinese flirtation. I think the Armed Forces of the Philippines at best is not going to support any attempt by Duterte to subvert the 2022 elections. The police, like the local political clans, will be a space for competition and negotiation in the coming elections.

[1] Visaya is one of the major eight major languages in the Philippines, dominant in the Visayas islands.

[2] Hambogero comes from the word humbug or arrogant.

[3] Bugoy, similar to the term “hooligan” in English, is the colloquial term for “good-for-nothing” rebellious teens involved in street gangs or hooliganism.

[4] There is no accurate translation in English of Hambogerong bugoy but similar descriptions would be “tough street kid”, “street-smart”, “foulmouthed gangster”, “neighbourhood bully”, etc.

[5] “Digong” is Rodrigo Duterte’s popular nickname.

[6] A former city mayor in San Juan Manila, he was elected president in 1998 but ousted in 2001 through a combined impeachment trial for corruption and withdrawal of military/police support. He was convicted of corruption but was pardoned in 2007 by former president Gloria Arroyo.

[7] Mar Roxas ran as president in 2016 under the Liberal Party, the political party in power at the time (2010–2016).

[8] Cubao, a rich business district of Quezon City.

[9] The term given to someone who has the simple/naïve bearing and attitude who comes straight from the provinces—probinsyano for men and probinsyana for women.

[10] The leading economic elite families in the Philippines.

[11] Vice-President Leni Robredo won as a candidate of Liberal Party, the main opposition party against Duterte. The Vice-President has broad support from the progressive movements, centre-left civil society, trade unions, and business.

[12] Makati is the financial district in Manila.

[13] A mock theater play.

[14] The largest labour coalition of trade unions in the Philippines.

[15] Akbayan is a social-democratic political party which has fielded candidates in elections to the Lower House. They also have a party member who occupies a seat in the Senate.

[16] KMU is the labour centre of the national democratic movement.

[17] 1Sambayanan is an electoral movement coordinating the different groups of the opposition for the upcoming elections.

[18] Jose Maria Sison is the exiled leader of the Communist Party of the Philippines and presently lives in the Netherlands.