The 1922 tenants’ strike remains one of the most forgotten episodes of the struggle for rights in Mexican cities. From the edge of memory, this movement has inspired different urban movements in Mexico over the past 40 years. Its ideals remain valid. The slogan posted on thousands of front doors in Mexico 100 years ago read “I won’t pay rent, I’m on strike”.

The power of the landlords, the neglected state of the properties that they leased, and the excessively high rents they collected was crystalized in a movement that emerged in the port of Veracruz and had repercussions for various Mexican cities, such as Mexico City, Guadalajara, Orizaba, Jalapa, San Luis Potosí, and even Ciudad Juárez.

Arturo Contreras Camero is a Mexican journalist who writes for Pie de Página, a partner publication of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation.

Translated by Leslie Pascoe Chalke.

In the port of Veracruz, the movement brought together more than 80 percent of people living in more than 100 courtyards and tenements in the city, which at that time comprised about 55,000 inhabitants. In Mexico City, these tenements housed a smaller proportion of the population, which by 1921 exceeded 900,000 people. Nonetheless, some 50,000 families joined the tenants’ union, an organization that formed as a result of the mobilizations.

Perhaps because the tenants’ movement was linked with the Communist parties of the time and because it challenged the privileges of the landlords, it was banished from discourse. It was practically buried in history for over 50 years until the beginning of the 1970s, when different urban movements revived it as an example.

A Century of Struggle

Celebrating the centennial of this strike, Carla Escoffié, director of the Human Rights Centre of the Monterrey Free Law School that specializes in urban and housing issues, stated: “I believe that this event can allow us to reflect upon several points and lead to a better understanding of the dynamics and complexities surrounding the issues of housing, leasing, and the city today.” She summarizes that the struggle was and continues to be a struggle for urban territory.

Historically speaking, Escoffié explains that land and the concentration of residential space has been a source of conflict. In Mexico, we have seen this unfold during the Revolution of 1910–1920, the Dirty War, the armed conflict in Chiapas, and even the War on Drugs, all of which include land as a component. Having clarified this, she continues to explain that considering that 55 percent of the people on the planet live in cities and in Latin America and the Caribbean this number climbs to 80 percent, then an understanding of new conflicts involving land implies thinking about the conflicts of housing and urban life, since leasing is a land-related matter.

Escoffié, who is also a lawyer, states: “When people are evicted, when a woman tries to rent a place on her own and is required to prove that she is married, when a landlord blatantly raises the rent, or when tenants do not have a contract, it is seen as an individual problem, as something that happens to an individual and that has nothing to do with the state or a political stance. In order to reconstruct the collective subject of our identity, as a foundation for these demands, we must learn from other movements such as feminism, the fight for LGBTQ+ rights, and indigenous movements.”

For this reason, Escoffié resumes, it is not surprising that the tenants’ movement 100 years ago in Veracruz was led by women, small-scale farmers, and the Afro-Mexican community, population groups that historically have been discriminated against for whom housing problems still weigh more heavily today. “The housing issue cannot be understood without taking into account the issue of discrimination against specific groups. People who rent find it difficult to purchase housing”, Escoffié claims.

Retrieving Organization and Memory

Rosario Hernández Aldaco, a member of one of the most significant political projects for autonomous housing in recent years in Mexico City, questions how it was possible for this great struggle to have been forgotten and why the tenants’ movement is no longer part of Mexican memory. Aldaco also suggests that “it was quite different then because there were no organizations at the time. They became organized and created a union, which seems highly germane.”

Hernández Aldaco forms part of the Francisco Villa Left Independent Popular Organization, a grassroots group which presented a self-managed political project involving construction and provision of housing in the late 1980s. She first heard of the tenants’ strike in a text written by the historian, Paco Ignacio Taibo II. In Bolcheviques: Historia narrativa de los orígenes del comunismo en México, which roughly translates to “Bolsheviks: Narrative History of the Origins of Communism in Mexico”, Taibo II devoted a chapter to the history of the strike in Mexico City. This extract, along with another one about the strike at the port, were published in a couple of pamphlets by the National Coordination of the Urban Grassroots Movement in the 1980s. These memories enlivened other movements in Mexico.

Nowadays, tenants are not seen as a group and the various groups existing around the issue of housing in the city are not articulated as a broad front, as they were 100 years ago. Undoubtedly, this is a result of the current discourse around housing as a meritocratic reward that depends on personal effort rather than a community’s needs.

Tenant demands are certainly still apparent but the memory of that almost legendary movement seems to be fading with time. Regarding this issue, Paco Ignacio Taibo II, in an interview for this article, pointed out that to preserve memories there is nothing to do but to write and talk about the subject so that other movements become aware of that history, which is precisely the purpose underlying those pamphlets that were even published under three different titles.

For Taibo II, the success of the movement of 100 years ago was largely due to two factors: “Its brilliant agitprop mechanics, as well as the self-management mechanisms that it began to generate: I don’t pay rent, but I use it to repair the place; I don't pay rent, but I use the money for something else. That happened not only in the strike in the Federal District, the previous name of Mexico City, but also in the strike led by Herón Proal in Veracruz.”

According to Escoffié, the lack of articulation or a clear project undermined the tenants’ organization in Mexico: “One of the things that most concerns those of us who are involved in these issues is that we see how the issue is unfolding in places like Spain, Argentina, Germany, and even the United States. There seems to be more articulation in these countries. It is not that Mexico lacks articulation, but during the past three decades the collective subject has been experiencing a process of very deep disarticulation.”

Escoffié explained that this process includes romanticizing large-scale real estate developments and companies that prioritize housing as meritocratic property, which responds to the efforts of the individual and luck. This moves the tenant issue away from the public realm and into the private sphere. “It is evident that there is an unwillingness to remember or highlight this strike in Veracruz because it is in conflict with the standards of housing financing in Mexico. This 100 year anniversary is an opportunity to reclaim that memory. Remembering this movement leads to the possibility of understanding that this is a matter of human rights”, reflects Escoffié.

The Mexican Congress is currently discussing a new national code of civil procedures that will define what eviction trials will be like nationally. This is an opportunity to provide more rights to tenants in Mexico.

100 years later, it is imperative to revive the collective memory of the 1922 tenants’ movement. María Silvia Emanuelli, coordinator of the Habitat International Coalition — Latin America, an international organization that promotes urban and housing rights, claims that it “is a forgotten movement, relegated to the shadows, that has hardly been analysed by academia and other sectors”.

“Right now, the (urban) movement is very much on the defensive, demanding no evictions, no rent increases,” a palpable problem in Mexico City given real estate speculation. Emanuelli regrets that “information regarding the prevailing dynamics of seizing control over the city is not disseminated widely”.

The Movement That Began in Veracruz and Spread Throughout Mexico

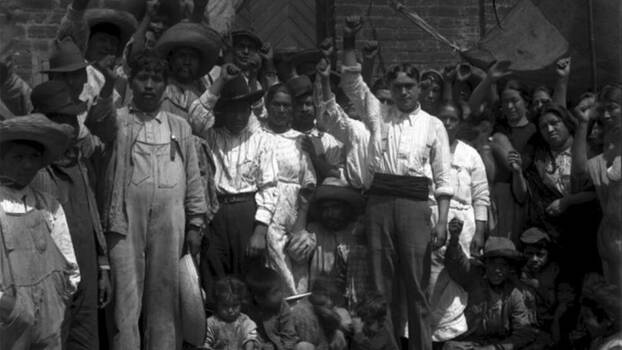

“Let the social revolution begin. Let the world tremble. Let the skies collapse. Let humankind shudder. Let Niagara Falls fall. Let the seas rise. Let the drainage system break down. Let electricity fail. Let the streetcars cease. Let automobiles blow up. Let the planet be razed. But don’t leave us without justice", urged Herón Proal at a demonstration on 27 February 1922, in Veracruz.

Days later, on 6 March, the “whore sisters”, as Proal called the group of sex workers known as Las Horizontales de Guerrero, which in English translates as “The Horizontal Women from Guerrero State”, burned the chairs, beds, and mattresses on which they worked, as a form of protest against soaring rents. During those days, protesting became common in the port of Veracruz, where almost half of the population took to the streets to denounce abuse by landlords. They rented rooms of a mere two-by-two meters in tenements that sometimes squeezed more than 100 or 150 homes into a building that had only one or two bathrooms, conditions that were considered unhealthy.

In those days, people stopped paying streetcar or bus fares since this was what Proal and his people had decreed: public transport pertained to the people and no one else. At first, many people would hide when a demonstration marched by but as the movement gained strength, many people identified with it and joined the cause. As Taibo II’s fliers stated, this was not out of mere solidarity but rather because it implied they would achieve better living conditions.

Meanwhile, in Mexico City, on 15 March, about 500 people gathered in the Salto del Agua square, summoned by members of the Communist Party who called all tenants to unite in order to work intensely against the owners of the disgusting tenement housing that was rented at exorbitant prices. In under a month, the call had spread like wildfire, to such an extent that demonstrations and protests were gathering thousands rather than hundreds in the streets, while affiliation to the recently created tenants’ union grew in equal measure.

Pedro Moctezuma, who has participated in many of the country’s urban movements over the past 30 years, claimed that “it was a very vigorous movement not only in Veracruz, but nationwide, and the result of a call by the Communists of that time to bridge the gap that existed in attending to many social needs that had not been met by the recent Constitution of 1917 or by the first governments that the revolution had brought”.

Women: Protagonists in Building Grassroots Power

Beyond the demands, Rosario Hernández of the Francisco Villa Left Independent Popular Organization recognized another very important parallel between the women living 100 years ago and those who are part of political housing movements today: “One of the things that occurs in housing organizations, which are numerous in Mexico, but something that happens in most of them is that it is women who have taken on the tasks of organization and work”.

During the strike, women were so important that they won historical recognition, according to García Nuñu in her article about it: “It was the men who gave strength to the Red Union of Revolutionary Tenants, but undoubtedly it was the women who made it invincible. Large numbers of women shoulder-to-shoulder with their undefeated comrades, contributed their energy, intelligence, and emotion.”

Rosario Hernández noted that this role is not due to the fact that women believe men are lazy or unwilling to participate but that in fact, within the division of labour, getting involved in organization and housing tasks implies having a more stable immediate future. “This furthers the possibility that women be seen as equal to men. We are no different from them and our equality enabled us to participate in a movement that used to belong to men, railroad workers, bakers, there wasn’t a movement of women cooks and so on”, Rosario stated.

The efforts of the Francisco Villa Left Independent Popular Organization began 33 years ago on the outskirts of Mexico City. “What we used to do then was look for plots of land, usually federal land, or land belonging to the government and we moved in to protect the plots. We would claim that we were going to safeguard them and proceeded to build some cardboard huts. This was a fight against the government because they wouldn’t let us move in and we had to defend ourselves. In the meantime, we would bring in water and electricity. That was the beginning. Today this is no longer possible and now we purchase land from private landowners”, explained Rosario.

“34 years ago, this form of struggle was very similar to what was done by the activists, the youngsters leading the movement 100 years ago, advancing it in the port of Veracruz. That was activism, the ability to engage with the people”, Rosario suggests. At first, it was not easy for Rosario, as she herself recounts: “The leadership positions were not for women. It was as if woman and I’m going to say it as a guy used to say, women comrades should be told to wear short skirts, stockings, and high heels, like an event hostess. That was the vision that prevailed.”

However, along the way she came across others like herself, who motivated her to dedicate over half her life to this project: “The women comrades, in everyday practice, through working together, shared their lives, shared their things, generating a dialogue in which we say: ‘No, if your husband hits you, don’t submit! That’s not allowed and you have to find a solution.’ In the commissions, the women comrades generate a life vision and the workshops that are given allow them to learn and step-by-step generate class consciousness. Whatever we are unable to do, no one will do.”

While 100 years ago people organized into a union, 33 years ago, Francisco Villa Left Independent Popular Organization was constituted as a political organization promoting the creation of self-managed housing cooperatives with a militant spirit that stands out in comparison to other urban movements in Mexico and other countries, in which the demands are focused on housing space in the city. Nonetheless, not all of these organizations are able to present a wider political objective.

At present, the organization was able to create seven self-managed communities that function around eight commissions: maintenance, surveillance, lists and finances, culture, health, agriculture, sports, and communication. They all form part of a life project, the organization’s political project that can be summarized as: creating consciousness and organization is to create grassroots power.