In some cases, notwithstanding the power of large corporations and state authorities, indigenous and small-scale farming communities in Mexico are successful time and again in defending their environment and living space peacefully against megaprojects on their territory.

In many cases, however, human rights activists in environmental matters attract the attention of local economic interests. Without protection, they become fair game—as in Paso de la Reina, a community of 500 near Mexico’s Pacific coast in the state of Oaxaca. The village includes an extensive ejido, communal land that is farmed on allotted parcels and cut by the Río Verde. The river is the third-largest in the state of Oaxaca and has a high water level, above all during the rainy seasons.

Gerold Schmidt has lived in Mexico for almost 30 years, where he closely follows the struggles of social movements as a journalist and occasional advisor.

In 2006, years of rumours coalesced into an official announcement by the state power company CFE: the company announced the construction of the Paso de la Reina hydroelectric plant, as well as other construction projects along the river in cooperation with the private sector. The implementation of the projects would not only have meant flooding extensive areas and, depending on the location, imponderables for local agriculture. The infrastructure required for machinery and material transport, as well as the non-local staff required for the construction of the dams, would also have drastically changed the living space and lifestyle habits of the rural population.

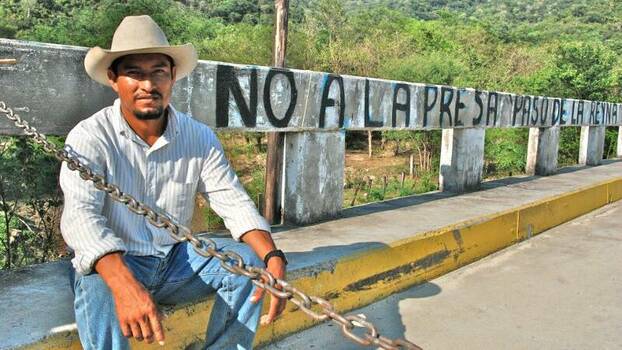

Within a few months, a resistance movement was organized among the local communities of the Sierra Sur mountain region and the coast. The population of Paso de la Reina played a leading role in this process.

Years of Mobilization

Back in 2007, the United Peoples Council for the Defence of the Río Verde, COPUDEVER, was founded. More than 40 villages with Indigenous, Afro-Mexican, and Mestizo populations joined together to resist the half-dozen dam projects along the river. They connected with the nationwide Mexican Movement of Dam Victims in Defence of Rivers (MAPDER), as well as initiatives in Central America.

COPUDEVER organized workshops with communities as well as demonstrations. During roadblocks, drivers received information on flyers. The council organized festivals on the problems of the Río Verde, held press conferences, and contacted national and international human rights organizations. Many meetings in the villages and audio-visual material about the Río Verde and the surrounding territories, in which the population had its say, strengthened the solidarity of the communities. In addition, numerous national and international organizations accompanied COPUDEVER and the community of Paso de la Reina in their stand against the proposed dams.

For years, the COPUDEVER communities took turns week after week in a camp at the access road to the Paso de la Reina ejido and thus to the river. It was a clear sign that they wanted to exercise control over their territory and put it into practice, as well. The case of Paso de la Reina became known nationwide, and the protests were temporarily successful.

So far, the projects on the Río Verde have remained in the planning stage, but were not officially cancelled. New concerns arose among the residents of the adjacent villages when a CFE helicopter overflew the river in March 2020. There are also frequent reports of attempts by the Mexican company ENERSI to obtain permits for smaller hydroelectric plants on the Río Verde.

Mexico has any number of environmental conflicts. Mining concessions, large-scale hydroelectric and wind power plants, illegal logging, discharge of toxic waste into rivers, and extensive monocultures represent a threat to the territories and day-to-day lives of many indigenous and smallholder communities. In hardly any other country do environmentalists live more dangerously than in Mexico. People who defend the environment, land and territory are often exposed to threats and criminalization. The number of murders committed against Mexican environmentalists has reached serious proportions.

According to the organization Global Witness, in 2019 alone nearly 40 direct attacks on environmentalists occurred in the country. Fifteen of them were murdered. For 2020, the Mexican organization CEMDA registered 18 murders of environmentalists, as well as a strong rise in the number of direct attacks (65) and other types of aggressions (90). The number of unreported cases is higher. The overwhelming majority of these crimes go unpunished, and impunity is widespread.

There is nothing to suggest that the trend will stop this year. The murders of five residents of the village of Paso de la Reina in the state of Oaxaca are a case in point. The murder of an environmentalist that became known recently only goes back a few days: on 21 May, in the municipality of Chilpancingo in the state of Guerrero, community leader Marco Antonio Arcos Fuentes was deliberately shot. He had publicly denounced illegal logging in his community Jaleaca de Catalán on several occasions without receiving support from state authorities.

Local Conflict

To a certain degree, the national attention given to Paso de la Reina has masked latent conflicts at the local level. In much of Mexico, local power elites continue to exert more influence than the federal government. Defiant communities like Paso de la Reina are a thorn in the side of such local power groups.

Even if protests do not target them directly, organized communities represent a potential challenge to their economic and often also political position. Paso de la Reina is part of the Santiago Jamiltepec district. In Jamiltepec, the Iglesias family has been known for decades for its political and economic dominance. When Gabriel Iglesias, the “local prince” and periodic mayor of Santiago Jamiltepec, died a few years ago, his wife Cecilia and their two sons continued the business. Currently, Cecilia Rivas is the mayor. “It’s like feudalism”, said an employee of a local nongovernmental organization who asked to remain anonymous.

The ejido members of Paso de la Reina report a current conflict with the family. They claim the family did not comply with agreements on the exploitation of the sand and gravel resources of the Río Verde on the ejido area. According to ejido residents, more material was removed than agreed and, moreover, not paid in full. On several occasions in 2020, tension arose between the ejido and the family. In spite of the business being private, transports were partially escorted by municipal vehicles and county police.

Death Threats and Murder

Under the new ejido president in office as of 2020, Fidel Heras Cruz, who had already been active in COPUDEVER for more than ten years, the municipality attempted to persuade the family to comply with the agreed terms and collect outstanding payments. At an ejido meeting in January 2021, the dispute over sand and gravel mining was openly addressed. Shortly thereafter, Fidel Heras found a death threat directed at him on a piece of paper in the ejidocommissary building. Two days later, on 23 January, he was found murdered in his car not far from the ejido entrance, shot in the head.

It was not to be the only murder. In the night of 14–15 March, deputy community leader Raymundo Robles Riaño and his two companions, Noé Robles Cruz and Gerardo Mendoza Reyes, were also shot. Unlike Fidel Heras, they were not in the public eye. But they too were committed to protecting the Río Verde and preserving their territory.

Only two weeks later, on 28 March, unknown assailants killed Jaime Jiménez Ruiz, a former local leader of Paso de la Reina. Like Fidel Heras, he belonged to COPUDEVER.

No Investigative Success

So far, investigations have not revealed crucial evidence about the murderers and masterminds. Many ejido members link the murders directly to the conflict over sand and gravel mining. Although no evidence has been produced for legal prosecution, they hold Mayor Rivas’s family responsible for the crimes.

On the other hand, all five victims were environmentalists who had taken a stand for the preservation of the Río Verde even before the current conflicts. It seems that the inhabitants of Paso de la Reina are being intimidated to keep their mouths shut once and for all.

Regional, national, and international organizations have called on the government of Oaxaca and the Mexican federal government to investigate the crimes and protect the ejido members of Paso de la Reina. The residents of the village have requested the deployment of the National Guard, but so far to no avail.

They do not trust the local police or the local judicial authorities. They remember too well the murder of the critical journalist Marcos Hernández in Santiago Jamiltepec five years ago. A local police commander was convicted as the perpetrator in the first judicial instance and sentenced to 30 years in prison—and released after two years due to procedural errors.

“Omnipresent Fear”

When asked about the recent crimes in his morning press conference in mid-April, Mexico’s President Andrés Manuel López Obrador evasively replied that no more hydroelectric plants like Paso de la Reina would be built under his administration. It would be sufficient to modernize the turbines of existing plants. But he did not mention concrete measures to protect the local population.

For the time being, COPUDEVER has decided to set up a checkpoint at the access road to the community. They hope that this will prevent further murders in the short term. In the medium term, the council and supporters only see a perspective if the government and authorities take concrete steps against impunity and carry out effective investigations.

Journalist Pedro Matías describes the current situation in Paso de la Reina in a report as an “instinctive curfew”. The fear of renewed attacks is omnipresent. MAPDER and COPUDEVER’s motto has never been more relevant: “Rivers for life, not for death.”