At a summit of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization in the Uzbek city of Samarkand, politicians from Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and China signed a treaty for the construction of a common railway line. Planned as part of a southern traffic corridor connecting China, Europe, and the Middle East, the railway is set to run from Kashgar in East Turkestan (the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in China) to Tashkent, Uzbekistan, before connecting to railways crossing Turkmenistan and the South Caucasus.

Emilia Sulek is a social anthropologist with a focus on Central Asia. Her most recent book is Trading Caterpillar Fungus in Tibet: When Economic Boom Hits Rural Area (Amsterdam University Press, 2019).

Translated by Sonja Hornung and Ryan Eyers for Gegensatz Translation Collective.

The Chinese and Uzbek sections are complete, but construction on the Kyrgyz part — the topic of this article — has yet to begin.

A Long and Winding Rail

The idea to connect China, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan (CKU) by train was hatched in 1997 during a meeting of the Transport Corridor Europe–Caucasus–Asia (TRACECA), a Eurasian transport funding programme. This would improve transport to Europe, while at the same time facilitating connections between inland Asia and the sea via the rail networks of Afghanistan, Iran, and Turkey. In the same year, a trilateral meeting took place and a cooperation agreement was signed. Direct conversations between Kyrgyzstan and China began not long afterwards.

The first decade of the new century saw a great deal of political turbulence in the region. Askar Akayev, the first president of independent Kyrgyzstan, was forced to stand down in the wake of the Tulip Revolution in 2005. In neighbouring Uzbekistan, hundreds of demonstrators protesting the authoritarian policies of then-president Islam Karimov were killed in the Andijan massacre. Another Kyrgyz president, Kurmanbek Bakiyev, stood down in 2010. In the south Kyrgyz province of Osh, disquiet between Uzbeks and Kyrgyzs further worsened attitudes towards shared plans for a railway.

Although political relations in the region subsequently cooled significantly, representatives of Kyrgyzstan first undertook multiple trips to China before they finally signed a contract with the China Road and Bridge Company (CBRC) in 2012 to carry out a feasibility study for the project. The study’s focus, however, was only on a route that — broadly speaking — convinced Kyrgyzstan the least. One year later, President Almasbek Atambayev announced that Kyrgyzstan would not invest in the railway as it saw no benefit in the venture.

The financial crisis that hit Russia in 2013 brought with it further changes, pushing Kyrgyzstan to work more closely with China. That same year, Beijing announced its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which heralded a phase of increased Chinese engagement in infrastructural investments in connection to its planned reactivation of the Silk Road. Interregional relationships improved when Shavkat Mirziyoyev assumed power in Uzbekistan in 2016. That said, even as the atmosphere relaxed, no significant progress was made on construction plans for the railway.

Discussions on the CKU railway only restarted in earnest after the Russian attack on Ukraine in 2022. In May, Kyrgyz president Sadyr Japarov announced construction work would begin in the following year.

Neither the timeline of construction works nor the financing of the project have been made transparent to date.

This surprising announcement took place in a completely different geopolitical context to the one in which the idea for a CKU line first saw the light of day. In a year that was characterized by the Russian attack on Ukraine and related international sanctions, the transport of products via Russia was for many reasons no longer favourable. Until this point in time, the northern transport corridor through Kazakhstan, Russia, and Belarus had been the preferred route. The southern route had less advantages, as the dense patchwork of border-crossings in Central Asia were fraught with bureaucratic hurdles and logistical difficulties.

However, it now appeared that the southern corridor could become an attractive alternative. The construction of the Kyrgyz section of the CKU would mean that the transport of goods from China to Europe would be around 900 kilometres shorter and seven to eight days faster than for containers travelling through Russia. Although the route through Kyrgyzstan would not replace the northern transport corridor, it was argued that it would diversify train connections, thereby bolstering independence from Russia, which would benefit not only the Chinese economy, but also its partners in Europe and the Middle East.

Conflicting Interests

Mountainous Kyrgyzstan does not really make for ideal train-track terrain, although the country already has two railway lines. After the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, Kyrgyzstan inherited two sections running through the country’s north and south: 424 kilometres of rail in total.

From the capital city of Bishkek in the north, it is possible to travel by train both to the Uzbek capital Tashkent and to Almaty, Kazakhstan. There is also a seasonal connection to the Issyk-Kul Lake, a popular tourist destination. The northern railroad provides transport for people as well as goods, while the southern section services freight trains only, and runs through the Kyrgyz cities Osh and Jalal-Abad and on to the Uzbek city of Andijan in the economically significant Fergana Valley.

In theory, all three countries have strong motivation to improve their transport systems — in practice, however, their interests diverge. Both China and Uzbekistan seek to intensify trade not only with foreign markets, but also with one another. With 30 million inhabitants, Uzbekistan is the most populous country in Central Asia. Chinese producers regard it as a small but useful export market, while Uzbekistan looks to export cotton and oil to China.

The CKU railway will grant China’s state-owned National Petroleum Corporation further access to an estimated 30 million tonnes of oil from Uzbekistan’s Mingbulak oilfields. Although these oilfields would satisfy only a fraction of China’s demand for oil, China’s current policy to diversify oil imports means that their significance has increased.

For Kyrgyzstan, the CKU line would lower import costs for many products currently still transported by truck. This is not immaterial: Kyrgyzstan imports more than it exports, and more than half of its trade is with China. Accordingly, the CKU railway project enjoys broad support among the Kyrgyz population. According to Emilbek Dzhuraev of the Soros Foundation’s Kyrgyzstan branch, “Liberals and conservatives, regime and opposition — almost all stakeholders support an improved transport network. The railway will enable faster and less expensive transport.”

Should the line go ahead, Kyrgyz minerals, animal products, and foodstuffs would all be able to be transported to China by rail. Kyrgyzstan also anticipates profits from freight charges to the tune of 200 million US dollars per annum, although critics consider these estimates overoptimistic.

The CKU railway would also bring additional benefits to Kyrgyzstan, including improvements to its internal transport system. Once an integral part of the Soviet railway network, the two Kyrgyz lines existed in a geographical no-man’s land after the collapse of the Soviet Union. The government in Bishkek now hopes to finally connect them.

As with many large-scale infrastructural projects, the promise of new jobs looms large. Chinese construction companies, however, prefer to use their own subcontractors, meaning that it remains unclear how many jobs will in fact materialize for Kyrgyz people. “Jobs are not created by infrastructure alone”, says Dzhuraev. “They must first be proactively created along the entire railway, and this is Kyrgyzstan's task, not China’s.”

Diverging Paths

Many potential routes were taken into consideration during the planning process, before the selection was narrowed down to two options. The final choice proved to be a bone of contention.

From the onset, China pushed for the shorter option: the trains would enter Kyrgyzstan through the Erkeshtam Pass (3,005 metres above sea level) in the province of Osh, taking the most direct path to Uzbekistan. However, Kyrgyzstan’s interests would be better served by a longer route, beginning at the Torugart Pass (3,752 metres above sea level) located halfway along the border to China. Rather than running directly to Uzbekistan, the route would first pass through Kara-Suu, Arpa, and Karakeche to the centre of the country. It would also connect with the railway that runs to Balykchy at Issyk-Kul. In this form, the CKU railway would contribute towards building much-needed transport connections between the country’s north and south.

A longer route for the railway, running through the heart of the country, would bring Kyrgyzstan numerous advantages and positive spillover effects for a large area. The Bishkek government hopes that the CKU line will improve transportation not only of goods, but also for people.

Currently, Kyrgyzstan is dominated by road transport, which brings with it considerable difficulties. On the highway from Bishkek to China, which runs through the Dolon Pass (3,030 metres above sea level), trucks overtake buses packed with passengers. The road is dangerous — in winter, it is often impassable. The same applies to the highway connecting Bishkek and Osh via the Ala-Bel Pass (3,175 metres above sea level).

Ostensibly, Kyrgyzstan's interests correspond with the official narrative of China’s BRI. The improvement of transport both on the continent and within the country is a central concern in Kyrgyzstan’s considerations regarding the CKU line. For Kyrgyzstan, transport must be improved both for goods and for people.

A longer CKU line would bring new life to a number of regions that have historically tended to lag economically, and it is equally clear that a shorter railway would not foster this much-needed economic boom. As President Atambayev said in 2017: “We don’t need railways that do not stop in Kyrgyzstan.” These words are as valid now as they were then.

The Fourth Actor in the Drama

From the wings of the stage, a further actor is also playing a part in the discussions around the CKU line: Russia.

Russia closely tracks and seeks to influence the actions of Kyrgyzstan and its neighbouring countries. Kyrgyzstan is politically dependent on Russia, although it tends to orient itself economically towards China. These economic relationships, however, do not extend to the political field. For Kyrgyzstan, Russia is a guarantor for security (or lack thereof), and a jobs creator for thousands of Kyrgyz citizens — almost one third of Kyrgyzstan’s GDP comes from remittances from guest workers in Russia.

Russia has resisted the CKU railway’s completion for years. A rail corridor in the south of Central Asia would pose a threat to transport routes through Kazakhstan and Russia, while improvements to transport infrastructure in south Kyrgyzstan would deprive Russia of income from freight charges.

As a country with a clear divide between north and south, Kyrgyzstan’s regions differ vastly in their demographic and economic make-up.

When asked why negotiations on the CKU railway are taking so long, Murat Sadybekov, an officer of the Kyrgyz railway service, conceded that “our big brother in the north has blocked the matter”. It is certainly a controversial issue, which is why “Sadybekov” is quoted here using a pseudonym.

In 2013, Russia suggested the construction of a number of rail connections between Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan — notably excluding China. Ever since China launched the BRI, however, it has become the heaviest economic weight driving construction in the region.

After years of blockade, Russia suddenly accepted the CKU line plan. What does this shift in opinion mean? “It certainly has nothing to do with us”, says Emilbek Dzhuraev of the Soros Foundation. Kyrgyzstan is far too small a player for Russia to seek to curry favour with. Far more likely is the possibility that the Kremlin is looking to “link up” to an alternative south route due to international sanctions and the discontinuation of routes running through Russia itself, Dzhuraev says.

The war in Ukraine means that Russia has become heavily reliant on its relations with China. Its policy change on the CKU line is a tactical move, signalling that the Kremlin will not interfere with Chinese interests in the region. Uzbek lobbying has also contributed to the CKU being given a green light. The country is experiencing a phase of economic recovery under Mirziyoyev’s leadership, the, and a railway with China would help facilitate an increase in trade.

The CKU line also has military significance, notes Sadybekov, reminding us of the fact that a decade ago, Russia pointed to the regional security threat that a rail connection to China would pose. The fact that Russia now supports the CKU line should also be seen in these terms. “If the conflict in Ukraine expands to Central Asia, it will be easier to relocate the army. Suddenly, it will not be televisions, cotton, and oil using this railway line, but tanks and troops.”

Bridging North and South

The CKU line is also of strategic importance to Kyrgyzstan. As a country with a clear divide between north and south, Kyrgyzstan’s regions differ vastly in their demographic and economic make-up. Provinces in the south are more densely populated and poorer. The south also considers itself politically underrepresented: the official language is the dialect from the north, where most of the country’s presidents also come from.

In general, the mode of political communication mirrors the lack of ties between regions. The country’s interior suffers particularly, with cities such as Kazarman granted peripheral status despite their central location. The construction of a highway from Bishkek via Kazarman to Osh in the south is one element of a deliberate policy to improve connections in the interior. A new rail line could also play a crucial role in this effort.

The southern provinces represent a controversial region for Kyrgyzstan. While the northern border with Kazakhstan was agreed upon in 2001, the southern borders with Uzbekistan and especially Tajikistan are still disputed. Conflicts frequently erupt on the border with Tajikistan, and have gained in severity in recent years.

This can be seen in the bloody struggles in the Batken Region, where the Tajik army has attacked the Kyrgyz border on multiple occasions. The complex ethnic structure of the area, as well as conflicts around water use — an essential resource, particularly given the Fergana Valley’s high temperatures — do little to ease the situation.

Who Foots the Bill?

Kyrgyzstan is often reduced to the position of problem child in the debates surrounding the CKU line. Beijing and Tashkent accuse the Bishkek government of being incapable of making decisions and of lacking funds. However, Kyrgyzstan should not be judged for protecting its own interests, in particular because one of the players in this game — China — is well-known for its colonial inclinations.

Projects realized within the BRI framework are not a form of infrastructural philanthropy, but rather seek to generate profits that will flow primarily to China itself. While China is likely to see immediate gains from the CKU line, profits for Kyrgyzstan will be less obvious and will transpire over a longer period — while its costs, by contrast, will be high.

The approximately 280-kilometre-long Kyrgyz section of the railway will require the construction of 48 tunnels and more than 90 bridges, often at more than 3,000 metres above sea level. The Kyrgyz rail network estimates that an investment of 4.1 billion dollars will be necessary — a colossal sum, above all for Kyrgyzstan, a country with little fiscal wiggle room.

Kyrgyzstan does not have sufficient funds at its disposal for the construction of its section of the CKU, and in any case, the majority of projects realized under the umbrella of the BRI are not paid for by hosting countries. And Russia? The notion that the Kremlin would finance a section of the railway that does not even run through Russia may sound surprising, but in 2020 Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov announced that the Kremlin would be willing to contribute to the costs. To date, however, Bishkek’s hopes for financial support from Russia have proven to be in vain.

The handful of details published after the Samarkand summit demonstrate just how closely interlinked the various forms of business that accompany the BRI are.

China is willing to provide Bishkek with a loan for the project. The issue here is that Kyrgyzstan’s state debt has already risen to a sum of over five billion dollars, over a third of which consists of debt to China. In many parts of the world, China’s BRI has revealed itself to be a debt production machine, which can then be used to gain political leverage. Cases such as that of the port of Hambantota, leased to China for a period of 99 years due to Sri Lanka’s insolvency, are well-known in Bishkek.

Tiny Kyrgyzstan, which shares 858 kilometres of its border with China, is justified in its cautious approach to taking on loans from its powerful neighbour. In case of insolvency, resource-rich Kyrgyzstan would likely be forced to relinquish land or mining rights to China — a possibility that could even play to Beijing’s advantage.

Above all, environmental damage and the country’s debt are the central focus of criticism of the CKU line in Kyrgyzstan. While constructing the railway is technically possible, it will require an enormous geological incursion into the country’s mountainous region.

Above and beyond the building of the infrastructure itself, critics fear that the railway will further facilitate access to mineral resources in its proximity, leading to intensified exploitation. This topic looms large in debates around the CKU line, with Kyrgyz politicians emphasizing their plans to increase exports of gold, aluminium, and iron ore. The export of natural resources represents a substantial proportion of Kyrgyzstan’s GDP.

Critics say that the government lacks a programme to stabilize the economy, drawing instead even more strongly on the exploitation of natural resources.

Gauging the Track

Transport along the CKU line currently takes place through a number of different modes. Containers arriving by train from China are loaded onto trucks and driven to Uzbekistan, where they are subsequently reloaded onto trains. This means that transport from Lanzhou in China to Tashkent (4,380 kilometres) takes seven to ten days. A journey via train would be faster, but there is another problem: railroads in China and Kyrgyzstan have different track gauges.

Chinese railways have a gauge of 1435 millimetres, while train tracks in Kyrgyzstan — as in other former Soviet countries — are 1520 millimetres wide. This means that a station will have to be constructed in which trains can be converted from one gauge to the other.

The exact location of this station has been a matter of further controversy. Kyrgyzstan envisaged that it should be located at its border to China. Beijing, however, holds that countries with which it builds new railways must maintain Chinese standards and build tracks with Chinese widths, meaning that China retains its own extraterritorial track standards in neighbouring countries. For those Kyrgyz citizens who consider the Soviet Union to represent a form of colonial domination, the notion that China would provide loans exclusively for a railway that meets its own needs — rather than Kyrgyzstan’s — amounts to a repetition of history, only in a neoliberal world.

Mixed Prognoses

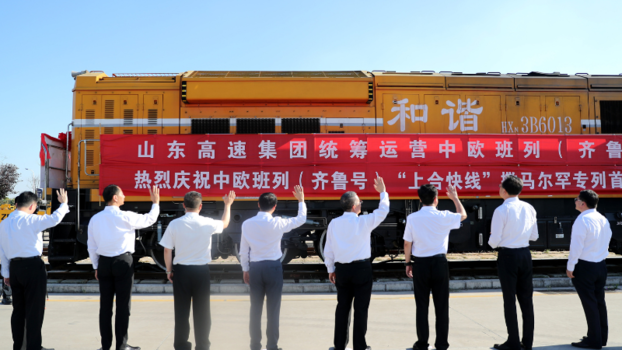

The summit in Samarkand confirmed construction plans for the CKU railway. The media disseminated images of the trilateral consultation process, and reported that a cooperation agreement had been signed confirming that construction would begin in 2023, pending further technical analysis.

This development was met with euphoria. Above all, it demonstrated the fact that Russia had not vetoed the project. But further details in relation to the construction remained unclear. “We have been conducting technical analyses for years”, Murat Sadybekov of the Kyrgyz rail service says. “At such a late stage, I would have expected more information.”

In fact, neither the timeline of construction works nor the financing of the project have been made transparent to date. It has only been announced that the CKU line will run from the Torugart Pass through the cities of Arpa, Makmal, and Jalal-Abad before connecting to the pre-existing, Soviet-era railway line in Uzbekistan. In Makmal, the CKU railway is planned to connect with the Kyrgyz railway crossing the country’s north.

In other words, it appears that events are unfolding in Kyrgyzstan’s favour. Makmal, however, houses a Soviet-era gold mine that was closed in 1998 due to unprofitability. Not long afterwards, the Chinese company Manson Group LLC, which currently holds 70 percent of shares, won a tender for the modernization and expansion of the mine. It has since become clear that Chinese trains will be converted to the Kyrgyz gauge only in Makmal — located almost 150 kilometres away from the border.

The handful of details published after the Samarkand summit demonstrate just how closely interlinked the various forms of business that accompany the BRI are. Improving the transport system is equally important as China’s earnings from trade and its exploitation of natural resources.

Despite the euphoria around progress in negotiations, the mood in Kyrgyzstan is subdued. According to a study by the Central Asia Barometer in Bishkek, almost 90 percent of the population are critical of Chinese investments in Kyrgyzstan and afraid of debt traps. Will construction actually begin in 2023, and hopes be fulfilled? “I would be cautious”, says Sadybekov. “I've heard all too often that construction work is about to begin.”