There is little space in the Garden Library. We are sitting together with Tugud Omer Adam in a stuffy room with a low ceiling two floors underground. There are hardly any books in sight and the bare concrete walls are a visual reminder that this functional building still serves as air-raid shelter. Tugud explains:

We did not decide to come to South Tel Aviv. Nobody hands out maps in the Sinai Desert in Egypt that show the location of Levinsky Street. After we refugees had crossed the Egyptian–Israeli border, the [Israeli] border policemen gave us bus tickets to the central bus station in Tel Aviv. We arrived there and were left to fend for ourselves. We were totally disoriented and knew nobody. Thus we just stayed where the bus had dropped us off. Those, who arrived later, gradually over time, had already a good reason to stay in the area – the support they could get from those who had arrived earlier; they had settled in and were familiar with the place.

In his homeland Sudan Tugud Omer Adam faced persecution by the authorities because he was politically active at the university. Like many other Sudanese he managed to escape detention by fleeing to the neighbouring country to the north, Egypt. When his situation there became precarious, he continued his flight, was kidnapped by human traffickers belonging to a network that operates across borders between Eritrea at the Horn of Africa and the Mediterranean coast in Egypt, and brought to the notorious torture camps on the Sinai Peninsula. The traffickers blackmailed his family; and after the ransom had been paid, they took him to the Egyptian–Israeli border. Across the last few meters he had to run for his life. It was a matter of luck, he emphasizes. Other refugees there were shot and killed by the Egyptian border police.

Several times a week, especially on the many warm and sunny days, Tugud and other volunteers from the refugee-community together with Israeli activists take the children’s books out of the boxes in the shelter-library and bring them to Levinsky Park. These books, in a dozen different languages, are available to the children of the neighbourhood. Dozens of children eager to read dominate the park for several hours. There is also much activity in the park at any other time. Refugees, adults and teens, as well as other non-Jewish migrants are meeting in the little park in South Tel Aviv all the time, day and night. Their oasis is encircled by heavy traffic, they manoeuvre around the drug addicts lying or sitting there, while talking loudly into their mobile phones. The three- to five-story tenement blocks in the area are sooty from the air pollution caused by the traffic; the balconies are closed off with bricks in a makeshift manner; satellite dishes, exposed wiring, and air conditioners installed in an improvised manner give the impression that one is no longer in the high-tech city of Tel Aviv envied by the entire world for its start-ups. The barely visible glass tops of modern high-rise buildings in some distance are the only reminder of that high-tech world.

The Infiltrators

Since 2013 no new refugees are arriving in South Tel Aviv. At the time Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu kept his promise and built a 245-kilometer-long wall along the Israeli–Egyptian border. Since then Israel is seen as a pioneer of a fortress-policy aimed at keeping out refugees and migrants. US President Donald Trump pointed to the Israeli wall as a model for the wall he plans to build along the Mexican border. And indeed, by building this wall Israel has completely sealed itself off so that virtually no refugees enter the country.

But it does not stop here. Refugees who are already in Israel are supposed to leave as well. Between 2006 and 2013 some 65,000 refugees arrived in Israel via the Israeli–Egyptian border on the Sinai Peninsula. About two thirds come from Eritrea. They fled from a dictatorial regime, from recruitment into military service that may last for decades, and from forced labour and slavery, including the sexual enslavement of women. About a quarter of the refugees are survivors of the genocide and the war in Sudan. More than 5,000 were subjected to torture during their flight. Yet the Israeli authorities merely recognize about one percent of them as refugees. By contrast, 84 percent of those fleeing from Eritrea are recognized as refugees elsewhere in the world, and 64 percent of those fleeing from Sudan.

In order to justify their policy, the Israeli authorities officially designate the refugees as “infiltrators”. For that purpose, the government makes use of a law for the prevention of infiltration passed in the 1950s. The law was meant to target Palestinians who had fled or were expelled to neighbouring countries during the 1948 War and afterwards tried to enter Israel in order to recover property they had left behind or to move back into their homes. Later the law was employed against the fedayeen: armed fighters who came from Egypt to Israel in order to commit terror attacks against the young state. The current usage of the term brands the refugees as dangerous and violent and thus they are not perceived as human beings in need of assistance and protection. At the same time, only refugees who arrived via the Sinai Peninsula, in other words people with dark skin coming from sub-Saharan Africa, are designated as infiltrators. This distinguishes them from other groups of people who enter Israel illegally, arriving by plane, mostly from Eastern Europe, and are white. Thus there is no need to explicate the discrimination based on skin colour and origin in a law and make it clearly visible.

Israel usually denies refugees from Africa access to a regular asylum procedure, but is unable to forcibly return them to their countries of origin, since it signed the Geneva Refugee Convention, which prohibits refoulement. Therefore these refugees are given a tolerated status. They are obliged to renew their permits every two months at the office of the Authority for Population, Immigration and Border Control, which is a division at the Ministry of Interior. There is only one such office for all asylum-seekers in Israel. Long queues usually line up at the entrance. There is no proper waiting room, and the questioning refugees have to endure for the renewal of their permits is insulting, reflecting the contemptuous attitude towards them.

The refugees do not get a work permit. They are not entitled to medical care, other social services, housing or legal assistance – apart from schooling for their children. Since they have no source of income at all, they work without permit, mostly in kitchens of restaurants in Tel Aviv, at the many construction sites in the city or via temporary employment agencies as cheap cleaning personnel. The Israeli authorities turn a blind eye and do not enforce the regulations by law imposed on employers. Nevertheless the authorities deduct 20 percent from the refugees’ salaries, which are usually minimum wage or less. Supposedly, the money will be returned to the refugees once they leave Israel.

In addition, the refugees must expect internment at any time. In 2013 Israel built the detention centre Holot in the uninhabited desert in the south of the country especially for refugees. At times some 3,600 refugees lived in the camp simultaneously. With a nocturnal entry and exit ban, the conditions were those of an “open prison” in the middle of nowhere. The incarceration was based on an order issued by the Ministry of Interior and did not require a court order. Initially the period of detention at Holot was indefinite, later on the maximum duration was limited by court ruling to 20 months and afterwards to 12 months.

The policy of arbitrary internment and harassment in combination with deliberately targeted as well as ordinary racism caused more than 20,000 refugees to leave Israel by 2018.

At the end of 2017 the Israeli government embarked on an even harsher policy, encouraged by the rise of populist governments around the world designating human rights and refugees as “enemies of the people”. It closed the detention camp Holot, declaring that the camp is superfluous since all remaining refugees—about 38,000, corresponding to less than half a percent of the Israeli population—will be deported within less than three months to “third countries” (Rwanda and Uganda), if necessary, by force.

South Tel Aviv vs. the Refugees?

The Israeli government primarily justified its policy with reference to the difficult situation faced by the Israeli population, mainly in South Tel Aviv, where most asylum-seekers from Eritrea and Sudan live. Yet the policy and the demonization of the refugees mainly served other interests of the government. Among other things, it allowed to divert the focus of the public debate away from issues uncomfortable for the government.

Tel Aviv is known as “the white city”. But that is only half of the story, writes Israeli architect and theoretician Sharon Rotbard in his pathbreaking book White City, Black City.[1] Prior to the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, South Tel Aviv was actually a part of Jaffa, the big and bustling metropolis at the time. The newly built Tel Aviv, “the white city”, was designed as a European counter-model to Arab-Levantine Jaffa.

Rotbard calls South Tel Aviv “the black city”. Actually, this part of town has always been neglected. While physicians, state employees, and lawyers—well-educated Jewish immigrants from Germany or Poland with close ties to the state apparatus—usually took up residence in “the white city” and the affluent suburbs to the north, craftsmen and owners of small businesses, many Holocaust survivors as well as people from Levantine or Arab countries tended to settle in South Tel Aviv, for example in Neve Sha’anan, the quarter in which most refugees live today. In the 1920s Jewish immigrants built the quarter as a garden city in the form of a menorah. In contrast to the distinctly European centre and northern parts of the city, Neve Sha’anan was always a meeting place for Jews of different origins. Right from the beginning South Tel Aviv differed from the northern parts of town. It was characterized by lively activity in the streets and a rather Levantine, lower middle-class, proletarian lifestyle. Entire streets were dedicated to specific crafts or goods. For example, Levinsky Street was—and is still today—the spices street, where numerous small shops sell spices. A street nearby is lined with shops selling furniture, and another one with shops selling lamps. Already in the 1960s the neglect by the government and municipality was so severe that everybody who could afford it left South Tel Aviv and moved to the northern parts of town or to the suburbs. Small businesses, garages, and joiner’s workshops became the dominant feature of South Tel Aviv.

Yet the devastating blow came in 1993, when the old central bus station was closed and the new one opened. In absence of a proper railway infrastructure, busses are by far the most important public means of transport, both in urban centres and between them. The site of the old central bus station was just vacated and has not been developed since. As a result, almost all shops in the area closed for lack of customers. The spooky deserted streets and the high number of vacant buildings attracted shady businesses. Within a few years the area around the old central bus station turned into the only place in Israel where prostitution and drug trafficking could thrive in the open, that is in the street, in rundown shacks or shops.

The new central bus station is a massive brutalist concrete building located not far from the old station. It is truly an architectural monstrosity of 230,000 square meters with 1,500 shops on seven floors. Dozens of escalators criss-cross the building, but are usually out of order. The crooked corners turned into urinals within a few months. The middle class avoided the central bus station right from the beginning and thus the shops closed one by one until there were only jumble shops left. Some floors have been completely vacant for years, turning the bus station into a truly spooky place. The entire quarter has suffered from the oversized construction: 4,000 buses depart from the station every day causing severe air and noise pollution. As a result, Neve Sha’anan und the surrounding neighbourhoods definitely turned into the district of the precariat.

Just at that time Israel opened its doors to non-Jewish migration in order to reduce its dependence on Palestinian workers, for example in the construction business and in the low-paid jobs of the service sector. Since the 1990s thousands of legal and illegal non-Jewish migrants came to Israel. In addition there was an influx of quite a number of Palestinian and other Arab collaborators from the Occupied Territories and South Lebanon, whose collaboration with the Israeli security forces had been exposed forcing them to leave their communities. Many of these newcomers settled in South Tel Aviv. Communities of Latinos, Russians, Ukrainians, and Filipinos emerged. As in migrant communities all over the world, numerous shops were set up selling familiar food, such as pork or Asian spices, prepaid cell phones, and money transfer arrangements that do not require a bank account in order to send money to one’s family back home. Small makeshift churches were set up in many places. The migrants turned Tel Aviv and thus all of Israel into an open, multicultural space. Yet most Israelis avoided the area, and for those Israelis who had been living in the area for a long time, these developments caused further deterioration in their living conditions. For example, crafty apartment owners found a new way to enrich themselves: they divided their apartments into ever smaller units and demanded a horrendously high rent for each such “flat”, which is often just a few square meters separated from the next unit by makeshift plaster walls, with one shared bathroom for several “flats”. The migrants had difficulties finding accommodation elsewhere and had to accept such deals. As a result the state of the buildings deteriorated. Both government and municipality consistently overlooked such misuses, which would have been curbed elsewhere right away, since they were merely phenomena occurring in “the black city”.

These developments are closely connected with two issues of Israel’s general political landscape. In the German discourse Israel is primarily the place where Jewish refugees fleeing from Europe found a safe haven. It is indeed true that Israel was built by Europeans for Europeans; European elites shaped the country and are still over-represented in all major centres of power. Yet, for many decades already, the majority of the Israeli population is not of European origin. Apart from the Palestinian minority that already lived in the country prior to the establishment of the state and today constitutes 20 percent of all Israeli citizens, hundreds of thousands of Jews immigrated from Asia and Africa (called Mizrahim [“Orientals”]). Today they constitute about half of the Jewish population in Israel. The discrimination the Mizrahim suffered at the hands of the “European” Labour Party, which dominated Israeli politics in the first three decades, still has repercussions today.

During the general election in 1977 the Mizrahim revolted and helped the right-wing Likud to come to power. Since then, for nearly 40 years the Likud almost always headed the government, but has only partially kept its promise to facilitate social advancement for Mizrahim. The Likud does not favour a strong welfare state that intervenes in order to combat social inequality. The market was left to its own devices and thus the wealthy and powerful became stronger and wealthier, the poor and weak became weaker and poorer. The growing gap between the prosperous, dominantly European northern part and the marginalized, dominantly Oriental southern part of Tel Aviv provides a vivid geographical illustration of this state of affairs.

It was South Tel Aviv, the backyard of “the white city”, where the authorities sent the refugees by giving them the bus tickets. The authorities did not assist them upon their arrival and even refused to consider the option of dispersing the refugees throughout the country. At the same time, no steps were taken to establish appropriate infrastructures and social services. The arrival of tens of thousands of refugees who did not speak the local language and some of whom were traumatized overstrained the existing ailing infrastructure; the doubling or tripling of the number of residents in some streets was too much to bear for those who had lived there for a long time.

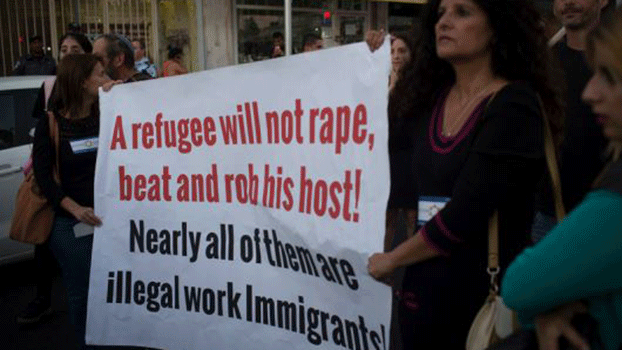

Instead of cooperating with the residents in order to work out concrete solutions, ministers and political decision-makers availed themselves to the effectiveness of resentment and blamed the refugees for all ills. Knesset-Member Miri Regev, who is today Minister of Culture and Sport, called Sudanese refugees in Israel “a cancer in our [nation’s] body”. Minister of Interior Eli Yishai threatened to “make their lives miserable”. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu himself intervened as well. Together with local activists he walked through the streets of South Tel Aviv and said that the refugees are a security threat and a demographic problem endangering the Jewish majority in Israel. The right-wing populist media, which is hegemonic in Israel, reported daily about allegedly criminal refugees and the suffering their presence caused for the local Jewish population. They labelled the many people who tried to help the refugees presumptuous leftists and liberals who do not care about the Jewish people and prefer to mingle with non-Jewish infiltrators, rather than with their poor Jewish fellows.

The Miracle of South Tel Aviv

For a while it seemed that the government’s plan to incite the veteran residents against the refugees would work. But then something approaching a miracle happened in the heated political atmosphere in Israel in recent years.

The physical and symbolic place of that remarkable phenomenon was a small run-down office, only adorned with posters of apparently Oriental women confidently looking towards the camera. The office is located in 70, Matalon Street, Neve Sha’anan. It is the office of Ahoti (“my sister”), a feminist Mizrahi organization, where women of different ethnic and national origins get together. Shula Keshet, who has her roots in Mashhad, a metropolis in north-eastern Iran, is the heart and soul of the organization; a colourful figure with her deep voice, her dogs and eye-catching jewellery; but most importantly, she is an intelligent analyst and highly experienced activist.

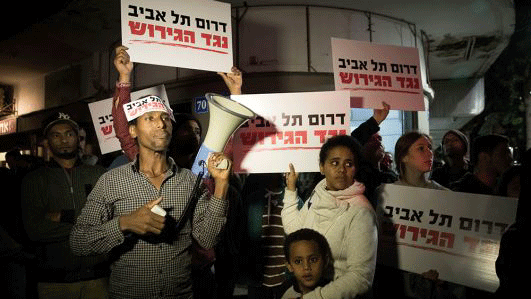

Keshet has gradually assembled an unusual coalition in South Tel Aviv, including veteran residents, mainly Mizrahim, and organizations working with children or refugees in the area, as well as activists from the refugee communities. The motto states: “South Tel Aviv against Deportation[/Expulsion]”. The ingenious idea is that the motto does not only refer to the fight against the government’s plan to deport the refugees, but also to the struggle against the impoverishment of South Tel Aviv that is destroying the local social fabric.

The conception was informed by the awareness that the city’s establishment had rediscovered South Tel Aviv by then. The municipal area of Tel Aviv is fairly small, comprising some 50 square kilometres, and there is no room for further expansion since Tel Aviv is surrounded by other cities. In addition, Tel Aviv is gaining importance as an economic metropolis, as is reflected in the fact that real estate in the city is now more expensive than in the vicinity of the English Garden in Munich. South Tel Aviv, located close to the city’s centre, thus harbours an enormous potential for real estate capital. The planning for the development of the area was undertaken without the participation of the local residents. Their interests are hardly taken into account. In light of the fate of other districts, as for example Neve Tzedek, a neighbourhood built by Mizrahim at the end of the nineteenth century that today has become the preferred residential area of diplomats and oligarchs, it is likely that the redevelopment of Neve Sha’anan and neighbouring quarters will entail an extensive change in the composition of the population and that veteran residents will be pushed out into the suburbs and hence lose the social networks which are crucial, particularly for those in the poorer social strata.

Combining both struggles led to a resounding success. Hundreds of posters against deportation/expulsion decorated the balconies in South Tel Aviv. Flyers were printed. Meetings were held. In the end tens of thousands participated in a demonstration in the narrow streets of South Tel Aviv. The demonstrators came to express their solidarity, to listen to the ordeals of Tugud Omer Adam’s flight, and to applaud Shula Keshet enthusiastically. It was a very impressive show of solidarity, and the campaign spread like a wildfire. People across Israel joined: elderly Holocaust survivors got in touch, offering to hide refugees in their homes; pupils, students, directors of schools, and writers composed touching open letters. All over the world demonstrations were organized in front of Rwandan embassies to protest against the country’s complicity in the deportation plans of the Israeli government. A slight shift occurred in the public discourse and opinion polls showed that the majority of the veteran residents of South Tel Aviv opposed the planned deportations. The Rwandan government withdrew its commitment to take in the refugees from other African countries whom Israel intended to deport. The Israeli government had to look for other target groups for its policy of fear.

Conclusion

The success of the coalition against deportation/expulsion was merely a victory in the first round. The danger of gentrification still persists in light of the dominance of the neoliberal market ideology in Israel’s political landscape; and the refugees’ fate is still unclear. Whether the refugees will be able or allowed to integrate into Israeli society depends on whether—and, if so—how Israel will balance the Jewish identity of the majority of its population with a modern concept of citizenship.

In France, for example, all citizens belong to the French nation. Israel was established as a Jewish state. It is a state open to all Jews who arrive in the country as refugees or migrants. They automatically receive citizenship. By designating the Jewish rather than the Israeli nation as the collective on which the polity is based, the two categories, Jewish and Israeli, are place on an unequal footing in terms of values. Not the Israelis, but rather the Jews—in theory, also including those living abroad who are not (yet) Israeli citizens—belong to the collective holding sovereign power, “the people” of the State of Israel. For that reason there are almost no legal provisions in Israel for granting citizenship to non-Jews. This excludes non-Jewish immigration, except for children of Jewish fathers (according to the Halacha, matrilineal descent determines one’s Jewishness) and individuals with Jewish spouses. Since there are nonetheless non-Jewish migrants in the country, they are defined as “foreign workers” who are supposed to leave Israel as soon as they have fulfilled their economic function. Accordingly, they should be prevented from settling in properly. That is the reason why some 100,000 non-Jewish migrants in Israel only receive temporary residence permits and why work-migrants are expelled when they get seriously ill or want to start a family.

That holds also true for the refugees from Eritrea and Sudan: since they are not Jewish, their status in Israel will always be temporary. What may be called the “raison d’Etat” is the reason why they will always remain foreigners.

South Tel Aviv is a microcosm of the struggles that will determine Israel’s future. The phenomenon of young people moving into the southern neighbourhoods of Tel Aviv in recent years and the overwhelming mobilization on behalf of the refugees show that there is an openness in Tel Aviv for a society that, to paraphrase Rotbard, is neither black nor white. There are many who want to live in an inclusive society and are also ready to work for it. It is still an open question whether those in Tel Aviv who successfully fought against deportation will be able to solve the broader issue of shaping Israeli identity in a way that it will become inclusive and open. The odds are not good given the well-oiled machinery of the now hegemonic right-wing nationalists, who will keep on trying to recruit the Jewish majority in Israel by invoking Jewish tribal identity and by promising privileges at the expense of non-Jewish migrants.

Tsafrir Cohen heads the Israel office of the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung. Einat Podjarny is programme manager at the Israel office of the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung in Tel Aviv. The essay was first published in All About Tel Aviv-Jaffa: Die Erfingung einer Stadt, eds. Hanno Loewy and Hannes Sulzenbacher (Hohenems: Bucher Verlag, 2019), on the occasion of an exhibition under the same title curated by Hannes Sulzenbacher in collaboration with Ada Rinderer and Hanno Loewy, at the Jewish Museum in Hohenems (Vorarlberg, Austria), on display from 7 April until 6 October 2019.