The agrarian question is the Left’s blind spot, and by far the most complex practical problem. Although in the second half of the twentieth century Marxism was primarily read as a “theory of industry”, this does not mean that agriculture and rural areas as a social space were not important moments in the analysis and political reflections of the first generation of leftists.

This issue played a major role in the constitution of the modern workers’ movement, in both its theoretical aspects (consider the idea of primitive accumulation or the struggles over ground rent in Marx) and its political ones. Wilhelm Wolff, to whom Marx dedicated the first volume of Capital, was one of the first to analyse the social and economic processes of agriculture, primarily as they were present in Prussia in the middle of the nineteenth century, and to draw political conclusions from them for the burgeoning communist movement. It was he who aggressively introduced the issue of alliances between peasants and workers into the discussion.

In 1894, Friedrich Engels took up this question under new circumstances and in relation to corresponding debates within German Social Democracy, discussing how to formulate its relationship to the different classes of the rural population. Yet the particularities of these social relations and agricultural production remained foreign to most of the Left. This goes back significantly to Karl Kautsky and Vladimir Lenin. They both analysed the development of capitalism in agriculture in their almost simultaneously published works on the agrarian question (1899).

Lutz Brangsch is an economist in the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung’s Institute for Critical Social Analysis. This article first appeared in maldekstra #1.

Adaptation to the City

Both authors emphasized the significance of breaking the dependence of peasants on capital, the cultural and social development of rural areas, the trend towards large-scale farming and the role of cooperative production. But they discussed all of this from the standpoint, as Kautsky put it, of a party that would always be a proletarian party. This explains why the peasants are primarily treated as potential proletarians or potential capitalists, and agricultural work as something to be converted into its industrial forms. The overcoming of the opposition between the city and the country was mostly not thought of as the overcoming of the division of labour (that is as a two-way process), but rather as the adaptation of the country to the city.

But even at this point there were already very different ways of reading the relationship between the agrarian question and overcoming capitalism. The Russian Narodniks refused the widespread Marxist view that the old peasant society would first have to be destroyed by capitalism before a non-capitalist society could emerge in Russia. Responding to a question raised by the Russian Marxist Vera Zasulich, Marx suggested that the Russian village commune, in which patriarchal and primitive communist elements overlapped, certainly had the potential to organize a transition to socialism without the intermediate step of a thoroughly capitalized agriculture. Yet he considered that a necessary condition for this was a strong working class and international solidarity.

In Russia, the Party of Socialists-Revolutionaries (SR), independently of and partially in opposition to Marxian ideas, defended the view that conditions in Russia meant that the peasants constituted a decisive force in the transition to a post-capitalist order. Not the dictatorship of the proletariat, but the dictatorship of “working people” was held to be the task of the present.

As a coalition partner with the Bolsheviks from November 1917 to April–May 1918, the left wing of this movement was the decisive force that bound huge swathes of the peasantry to Soviet power. Their agrarian programme involved a commitment to strong peasant economies on socialized land, which were supposed to develop collective forms of cooperation along the lines of the village commune.

This indicates how the agrarian question combines all the problems of social transformation in a particular way. The most important issues were controversies over the “revolutionary potential” of the peasantry, the connection between agricultural labour and labour in other sectors and so the prospects for the division of labour, and determining the potential of collectivist and other traditional forms of cooperation.

The alliance between the left-wing Socialists-Revolutionaries and the Bolsheviks rapidly broke down. In the Bolsheviks’ eyes the peasant, a potential capitalist, became an enemy and was treated as such. The price to be paid for this came in the form of rebellions marching under slogans like “Hooray for the Bolsheviks (who gave us the land)! Hooray for free trade! Down with the Communists (who requisition grain)! The rift between private land ownership and the communal distribution of the yields of that land must be abolished.”

Lenin and the Cooperatives

After interventionist and civil wars, the New Economic Policy saw the realization of a number of the SR’s ideas, even if they were not presented as such. The 1922 Soviet Land Code acknowledged the prospect of the village commune being one of the possible forms of agricultural activity—and in many areas it was indeed the reigning form until 1928. The establishment of more or less regulated market relations as part of the “state capitalism” strictly controlled by the party actually led to the stimulation of agricultural production. Questions regarding different perspectives were openly and thoroughly discussed.

An early result of this was Lenin’s position on the cooperative system. It was on the basis of this that the agrarian economist Alexander V. Chayanov developed his ideas about how the peasantry could be integrated into the division of labour in such a way that its production sites would not become capitalist enterprises. He was unable to prevail and fell victim to the Stalinist terror, his name largely forgotten in the world of actually existing socialism.

Yet his views proved inspiring for agrarian movements in other parts of the world. The fruitful cooperation that Chayanov strove for between industry and agriculture would remain a central and unresolved problem in the Soviet Union until the 1985 Food Programme. In general, it is and remains striking that the intensity with which agriculture and the countryside were ‘studied’ until the end of actually existing socialism, stood in contradiction to its practical achievements.

In the early Soviet Union, agriculture was mainly a source of foreign currency. Agricultural exports were the decisive means by which the machinery needed was purchased abroad. Yet the early Soviet Union did not manage to strengthen industry and agriculture in equal measure. Stagnation and a loss of face threatened the ruling stratum. They were confronted with the question of whether they should pursue a balanced but slower development of industry and agriculture, or rapid industrialization at the expense of agriculture.

The collectivization and industrialization policies from the second half of the 1920s onward as well as the extensive use of grain exports as a revenue source ruined Soviet agriculture. Industrialization, according to Soviet agrarian economist Mikhail Suslov, was bought at the price of the starvation of the rural population. The 1920s in the Soviet Union posed new questions for the Left: how and at what price food sovereignty could be attained and secured.

Garden Allotments and Agricultural Production

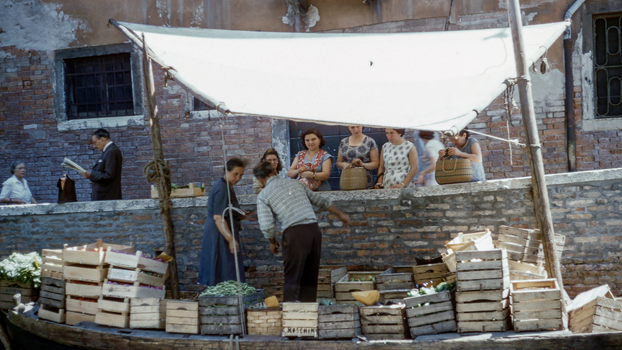

In Germany in the second half of the nineteenth century, the garden allotments of working families played a major role not only in securing food supplies but also as sites of politicization. Allotment associations were a way to get around the Anti-Socialist Laws, which were designed to throttle the then still revolutionary Social Democratic movement. What is today known as urban gardening was for the first generation of workers a necessary means of material, cultural and political survival. Even the consumer cooperatives were left-wing strongholds for a time.

For the doctor, writer, vegetarian, and Communist Friedrich Wold, food sovereignty, gardening and living close to natural surroundings were all related aspects of a life of self-determination. But this tendency would not become politically powerful within the Communist movement. Irresolvable contradictions arose in actually existing socialism between securing food sovereignty and the demands of an agro-ecological economy.

In the majority of socialist countries, the (more or less forced) collectivization and attempted industrialization on the Soviet model constituted the point of departure for both action and theoretical reflections. The importance of agriculture as a site of the reproduction of the biosphere, repeatedly emphasized in theory up until the 1980s, was not at all reflected in the planning system. Various cooperative forms developed in which the demands of agriculture were largely steamrolled by the ideas of planners and the producers of agricultural machinery.

Yet beyond the pursuit of mass production, domestic economies and allotments continued to exist and sometimes made considerable contributions to agricultural production. The Association of Gardeners, Settlers and Animal Breeders played a major role indeed in the GDR’s food supply.

So it seems that the experiences of the Left regarding this issue are highly problematic. Obviously the question of how to arrive at an ecologically, socially, culturally, economically, and politically sustainable agriculture poses a whole series of further questions to which the European workers’ movement, schooled as it was by industrial capitalism, found no reliable answer. The complex social structure of rural areas and the obvious impossibility of ever extricating ourselves from natural relationships demanded a much more sophisticated politics than was realized historically.