Surgentes—a word play between surgir, “to emerge”, insurgente, “insurgent”, and the compound word sur-gentes, meaning “south-peoples”—is a small human rights organization made up of five members, four of whom are women. Its mission is "to strengthen processes of organizing popular power so as to bolster demands for the enforcement and grass-roots protection of human rights, and to promote the structural democratization of society”. The members of Surgentes are left-wing activists with over two decades of experience in human rights activism.

They were active in the Venezuelan human rights movement until the early twenty-first century and later took on roles in government institutions related to police reform, and to the attempt to consolidate a security policy based on rights. They worked in the National Commission on Police Reform (Conarepol), in the creation of the General Police Council (CGP), and the National Experimental University for Security (Unes), in the Presidential Commission for Gun Control and Disarmament (Codesarme), and were part of the team that designed the Gran Misión A Toda Vida Venezuela (great mission for a full life for all).

In 2013 they returned to social and political activism with a focus on human rights.

In 2019 you studied police killings in the barrios. What were your main findings?

Antonio González Plessmann is a member of the Venezuelan human rights organization Surgentes. He spoke with Alexandra Martínez and Ferdinand Muggenthaler from the RLS Regional Office in Quito. Translated by Andrea Garcés Farfán and Joel Scott for Gegensatz Translation Collective.

The study used a quantitative approach based on national data, and a qualitative approach based on testimonies of the victims’ families.

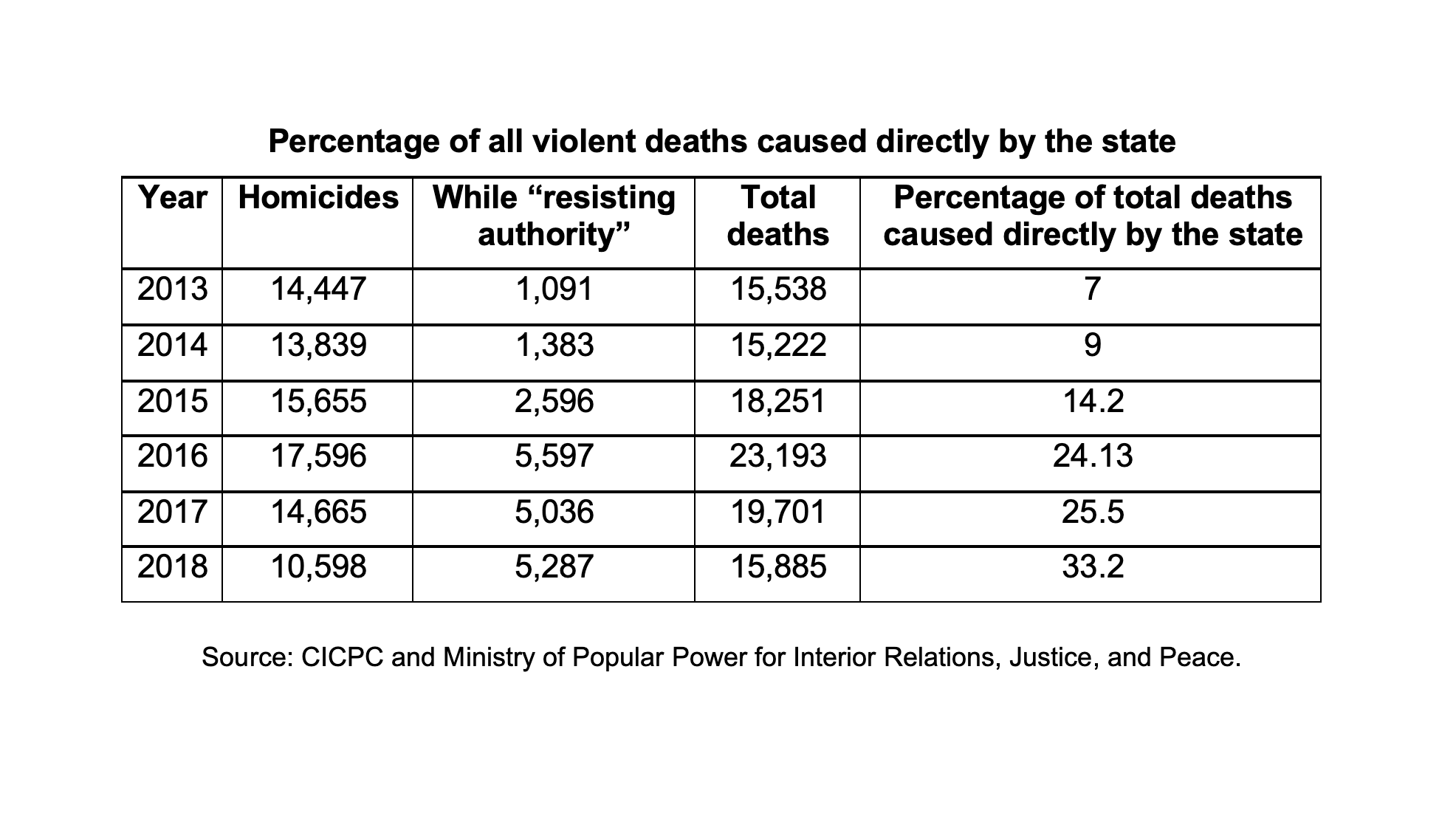

After processing the official national data, it becomes clear that the use of lethal force by police has increased significantly since 2013 (see table).

In absolute terms, the figures show a 384.6 percent rise in the number of deaths caused by state forces. If we compare the percentage of total violent deaths caused directly by the state there is a 374.2 percentincrease over the same period (from 7 percent to 33.2 percent).

On the other hand, the testimonies collected show that the murders committed by the police mostly affect young males from working-class areas who had been excluded from the education system, and who worked in the informal economy. According to the testimonies, some of these young men had been involved in criminal activity (mostly minor crimes) or had open criminal cases and were required to report to the court every 15 days. In other cases, the victims were young men without a criminal record who were not involved in criminal activity.

This killing of poor, marginalized youths qualifies as disproportionate use of lethal force, as all the victims in the cases studied had been subdued and disarmed. This shows a pattern of executions that contravene the current regulations that explicitly regulate the use of force.

In Venezuela, the term barrio (literally neighbourhood, suburb) generally refers to economically depressed neighbourhoods with significant social issues. Similar to the term favela in Brazil.

The homogeneity of the police conduct reveals a policing pattern behind these actions. Moreover, the lack of investigation or sanctions by state institutions suggests a sort of tacit endorsement of a “tough on crime” approach against low-level offending that leaves the structure of large criminal organizations intact. The lack of condemnation by high-ranking government authorities, who at times have even commended and praised these practices, is tantamount to their authorisation.

In their role as mothers, grandmothers, sisters, and aunts, women have to deal with the consequences of these young men’s deaths. Not only must they negotiate the procedures for retrieving the bodies and make an official complaint (in cases where this occurs); they also have to take care of the surviving children and support them financially, thus increasing and deepening the pre-existing economic difficulties of these families.

The concentration of violence in working-class areas and the crippling of the community’s capacity to protest are an effective mechanism of social control that does a disservice to the central role of the lower classes in the Bolivarian Revolution and its egalitarian and democratic approach. The negative effect of these practices on popular mobilizations is confirmed by the almost non-existing response by society and communities, as these cases are rarely denounced.

You used these findings to launch the campaign “NO MORE EXECUTIONS IN THE BARRIO”. What are your demands?

The campaign grew out of our own experience in these communities. FAES executed the son of a comrade from the Cooperativa Unidos San Agustín Convive and then claimed that he died in a “confrontation” with police. There were ten identical cases in our area over the course of six months. Our experience on the ground confirms the trends identified in our research. This topic, which is rarely or never discussed in the inner circles of Chavismo or on the Left, is a manifestation of class inequality and of the government’s change of course. With our campaign, we intended to contribute to reducing the number of murders of young men from poor sectors of the society by generating a debate within the left and within Chavista circles that puts pressure on the upper echelons of government.

FAES stands for Fuerzas de Acciones Especiales (Special Operations Forces), an elite corps of the National Bolivarian Police (PNB), which has been responsible for the majority of the suspicious deaths.

First, we are demanding that the government condemn the classist police violence that has been growing in our neighbourhoods over the past six years. Second, we ask that it reverts to the path sketched out by President Chávez with his police reform programme and his security policy, which showed respect for human rights and explicitly criticized classism. We also demand expedient investigations regarding extrajudicial executions and the creation of an interinstitutional coordination space to investigate the increase in the so-called “deaths while resisting authority”, which are clearly a way to cover up executions.

Why did you collect international signatures for the campaign?

Liberal human rights NGOs and those aligned with the opposition have been denouncing police violations of the right to life for some time. However, these reports don’t find resonance within Chavismo and the Left, partly because the political interests behind them (regime change) are all too clear, and partly because the widespread polarization in Venezuela makes it more difficult to recognize and understand the discourse of the adversary.

Our research and our campaign tried to look at the problem from a class-based perspective (highlighting that the main victims are poor people) and revealing the contradiction between a security policy that implies the death of young, low-level criminals (or youths from barrios not involved in any criminal activity) and the programmatic agenda of Chavismo and the left. The idea was (and still is) to increase the critical mass among the general public and amongst Chavistas and leftists—both nationally and internationally—in order to put pressure on the government to change its policies.

Making alliances with forces from the international left (parties, movements, intellectuals, and activists) that are not hostile to the Bolivarian Revolution, but, on the contrary, have even supported it, is one of the tactics we use to define the place from which we speak: we defend the democratic programme of socialist transformation developed by Chavismo, in which the people play the central role. It is from there that we question police violence and demand an end to it. In other words, it is because we defend the Bolivarian Revolution that we highlight the hypocrisy of the ruling elite and demand changes.

Were you able to get endorsements from the international Left?

It wasn’t easy to get them on board. Because of the complexities of Venezuela’s hegemonic conflict, leftist activists and organizations are very cautious with their statements. Which is understandable. Perhaps we need a more engaged form of solidarity, a kind of solidarity that is able to see and understand the nuances and internal tensions.

This seems to me like a small-scale example of asking for “international solidarity”. What do you think of that term?

I think it’s completely valid as a value that guides the articulation of different sectors of the international Left. Faced with the globalization of capital, leftist solidarity is a way of joining forces around ideas, principles, values, and small-scale programmes, that increase the Left’s relative weight. It’s not about asking that some people (those who can) help others (who are in need); it’s about the same struggle happening simultaneously in different places, expressed in different ways. A struggle that belongs to each of us, even if it happens beyond the borders of our country. Combatting imperialism, the unjust distribution of wealth throughout the planet, or systems of exclusion that make half of humanity expendable, or strengthening the possibility of a democratic society that would offer an alternative to capitalism, or the right of populations to self-determination—these are things that unite us across borders.

But don’t you think that international solidarity can also be a blinding concept? The ideal of a shared struggle is contaminated by a dynamic of “giving” and “taking” that can’t be avoided in our unequal world. That’s why we develop contradictory relationships that on the one hand can be based on critical solidarity, but on the other can be strongly shaped by geopolitics, paternalism, and projections. Venezuela is an example of this. Chavismo gave hope to many leftist movements and parties around the world. But then, with the economic crisis and an increasingly authoritarian government, two trends emerged: some adhered to an “unconditional solidarity”, defending the government at all costs, while others stopped talking about Venezuela and lost interest. How did you perceive this reaction in Venezuela?

I understand why part of the Left prioritizes the geopolitical dimension and closes ranks with the government in an uncritical manner. There is indeed an international siege. A fundamental element of the dramas that Venezuela is going through is a result of imperialist strategy.

Still, although I understand, I think this point of view is incomplete and strategically flawed. The dispute is taking place within a geopolitical and a national context, in which the class struggle is becoming more complex, as it now involves an emergent bourgeoisie that is reproducing an unequal social order under the cover of Chavista rhetoric. What they defend against imperialism vanishes in the internal order.

A politics of international solidarity with the Bolivarian Revolution must show solidarity with the most advanced aspects of its programme for a radical, democratic, and socialist transformation. It must question the siege head-on, but also the political elite’s drift towards liberal economics and authoritarian politics. It must develop a unique speaking position outside of “humanitarian” and liberal discourses, but it must also avoid the defeatist discourses of parts of the autonomist Left that end up saying that what the Venezuelan people did “was not worth it because they ended up repeating the past: rentierism, clientelism, extractivism, authoritarianism”. It must be a discourse that fosters from afar that which survives of the Bolivarian Revolution in the popular movement.

What do you expect from European leftist movements in this situation?

Like I said already: that they question the imperialist siege as well as the Chavista ruling elite’s drift towards liberal economics and authoritarian politics. That they build their own speaking position to support that which survives of the Bolivarian revolution in the popular movement, in the Chavista Left.

Is it just about creating their own speaking position? Or is it also possible to organize spaces to exchange experiences and learn from each other?

If we want to create a critical form of solidarity, one that is not automatic, it needs to be based on common principles, on shared readings, and some level of certainties regarding a strategic course of action. I believe that even though the world’s leftist movements are very different from each other, they still share a huge amount of common ground related to the radically antidemocratic character of capital and its effects on the lives of the majority. So we still have some very important common principles. Of course, we need to build spaces of trust, understanding, and mutual knowledge. This sometimes requires cultural “translations” (and not just in terms of languages) that allow us to contextualize situations or ideas. This would be the first step in our exchange, which would also allow us to learn from each other and strike balances. The second step is, clearly, to build agendas for a shared struggle. That’s where international solidarity should be headed.