It's about time! For quite some time now—ever since the hot summer of 2018 and the drought summer of 2019, ever since the forests of northern Germany burned in spring and the River Spree began flowing backwards, ever since the remarkable defence of the "Hambi" (Hambach Forest) against the coal dinosaurs of RWE and their public fossil-fuel henchmen in the state of North Rhine-Westphalia, ever since the embarrassing failure of the federal government's coal preservation round table, disingenuously named “coal commission”, and the directly related emergence of a new, young generation of climate activists in the form of its politicized avant-garde, “Fridays for Future”—probably the whole country (with the exception of some crazy climate deniers, that is, fascist deniers of reality) has known that this thing about the climate changing… it’s kind of important. Some have even grasped that rather than “climate change”, it would be better to say “climate crisis”; while the former implies a slow, linear process that might not be as dangerous, people broadly understand “crisis” as a terrible thing, as something we have to do something about. Obviously.

Translated by Kate Davison and Wanda Vrasti for Gegensatz Translation Collective.

What this means is that, although almost a decade has passed since it was repeatedly emphasized, in the lead up to what turned out to be the spectacular failure of the COP15 climate summit in Copenhagen, that we had roughly a decade left to avert the climate crisis, it’s only just now that the political system and the less climate-savvy sections of society are finally beginning to think about how we can save the climate within the next 10 to 30 years. Well done, but it would have been nice if the penny had dropped a bit earlier.

When it comes to dealing with the climate, climate protection, and all possible variations of the so-called “environment question”, especially since the environmental movement along with the Green Party split from the broader German left, the left is faced with the question of how these issues should be tackled from a left perspective. In other words, how can we move away from the widely spread misconception—sometimes even spread by our own hand—that environmental problems were bourgeois-post-materialistic-luxury-latté-problems, in order to make it clear that climate protection, which so far hasn’t been a barrow that any particular political persuasion has pushed but is now very much a popular demand, is in fact an absolutely core project of the left, and that the matter of climate change—er, crisis—is a problem produced by the left’s favourite old villain, capitalism, for which the only solution can be found beyond said capitalism?

Many leftists have found that the answer to this “framing” question lies in the term “climate justice”. The argument goes something like this: Sure, the climate must be protected, and the political force that has been primarily associated with climate protection has been those awfully bourgeois-post-materialist-luxury-latté-greens; in their capital-friendly confusion, however, they will try to confront the problem with “market-based” solutions, such as emissions trading or similar ineffective rubbish; instead of banal green “climate protection”, the problem demands serious left-wing “climate justice”, which, beyond the old climate nerd scene, doesn’t seem to amount to anything more than “climate justice = anti-capitalist climate protection or climate protection through the socialization of the means of production”.

Mind you, at least this term, which first entered the lexicon of a slow-but-steadily growing protest movement around the time of the first climate (and Antira) camp in 2008, has now become an important part of left-wing political discourse. Here too: Well done, but it could have happened earlier. That way, we wouldn’t still today be wasting time clearing up such misconceptions, which themselves are the long-term consequence of the nowadays rather embarrassing assertion (that is, representation) of ecological topics as polar-bear-hugging luxury problems.

The most serious misconception can be seen in attempts to unite issues relating to the “Aufstehen” campaign with the hottest pink-purple-green issues du jour, and can be encountered everywhere from the gilets jaunes to deep within Die Linke. Just weeks after the gilets jaunes announced that a day of action for “climate justice and social justice” would take place on 21 September 2019, Bernd Riexinger wrote: “It is the task of Die Linke to bring social justice and climate justice together within a left-wing, future-oriented program.” This patently well-meaning statement seems to be based on the following logic: “social justice”—a bread-and-butter issue for the traditional working-class left—is, at its core, about the redistribution of wealth at the local and national levels, whereas climate justice happens at the global level. What is irritating about this is that it represents a kind of methodological nationalism that constructs the social—meaning, society—as a national phenomenon. Furthermore, and this is of central significance here, it reveals a total misapprehension of what the concept of climate justice has meant thus far, what the history of the concept is, and what the demands of the movement for climate justice today actually are. In order to counter these misconceptions, I will first address the dimension of “injustice” associated with the climate crisis (climate injustice) and then explain the genesis of the climate justice movement and the meaning of the concept itself. It's about time that we understood this.

What is climate change really about? First and foremost, it’s about justice. This is because, on average, those who have contributed the least to climate change suffer the most and those who have contributed the most suffer the least. The latter usually have sufficient resources to protect themselves from the consequences of climate chaos. They have accumulated these resources, this wealth, through the very same activities that have driven climate change. This central fact, which incidentally applies to almost all so-called “environmental crises”, can perhaps best be described as climate injustice.

In order to better understand the claims and demands of the climate justice movement, it is worth taking a look at the history of social struggles, and more precisely the emergence of the environmental movement in the USA in the 1960s, which was first and foremost a movement of the white middle class for the white middle class. It originated in relatively privileged “white” neighbourhoods and cities, where its main objective was to keep these communities free from air pollution and prevent their children from being poisoned by chemical companies and power plants. As understandable as this objective was, it had an unfortunate effect: instead of these companies and plants being closed down and dismantled, they were simply relocated—from the richer communities to the poorer ones, whose residents were for the most part African Americans, Hispanics, Native Americans, and other marginalized groups. The struggles of this liberal environmental movement by no means solved the problems it criticized—instead they were simply shifted a few steps down the ladder of social power.

These communities of colour, upon which a whole host of dirty industries were suddenly imposed, were not just passive victims. Instead, they organized, accused the movement of “environmental racism”, and established their own movement for “environmental justice”. To put it in analytical terms: when seemingly environmental problems are not seen as social problems, and when awareness that a single dirty factory is in fact embedded in broader social structures of rule and exploitation is absent, then not only is the solution of those problems rendered impossible, but existing social inequalities are deepened.

As the debate about climate change gained momentum in the 1980s, there developed an idea of the climate problem as a primarily technical one, requiring solutions focused on reducing and remedying the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere through certain mechanisms. This, in turn, led to the development of so-called “market mechanisms” for combatting climate change in the 1990s. This approach—without engaging in the entire critical debate about these spectacularly ineffective environmental policy tools—was based on a technical fix that ignored social structures: every CO₂ particle is the same as any other, so surely it doesn’t matter who, where, and under what conditions CO₂ is conserved.

Economically speaking, it is best to save where it is cheapest, and it is easiest in the Global South, where everything is cheaper on average. So we could, for example, give development organizations money to protect forests from deforestation, which in turn would protect the climate while we continue to burn fossil fuels here in the Global North. However, there is a big catch to this idea: in these forests, which were suddenly earmarked for rescue from excessive deforestation, there were often Indigenous peoples, who for thousands of years have excelled in sustainable forest use and who were now being threatened with premature displacement from their traditional lands by the market mechanisms negotiated under the Kyoto Protocol in the 1990s, in a process of so-called “green grabbing”.

(Kopie 14)

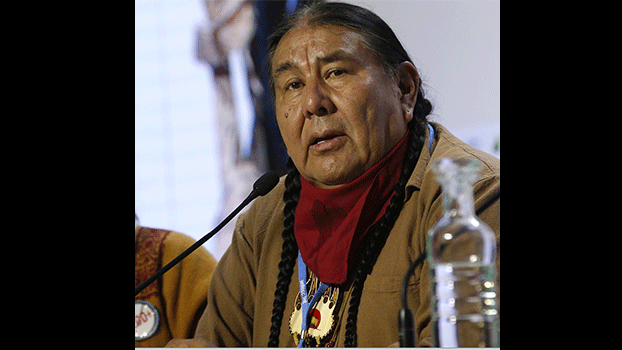

In the course of these negotiations, the story of environmental justice was once again taken up: in response to the “climate racism” of official climate policy, Indigenous American activist Tom Goldtooth, founder of the “Indigenous Environmental Network” with a long background in the environmental justice movement, formulated the demand for “climate justice” for the first time. This was the start of the struggle to reframe climate change as a question of human rights and justice.

The next step in the development of the climate justice narrative came with the publication of the Greenhouse Gangsters vs. Climate Justice report in 1999.[1] This report focused on fossil fuel companies, where instead of individual solutions (such as ethical consumption), it proposed major structural transformation. The fight for climate justice had finally been explicitly described as a global one. The report also formulated the movement's most important framework to date, namely, it dismissed the market mechanisms of the Kyoto Protocol as the “wrong solutions”.

In 2002, the organizations that would later form the core of the movement met for the first time in Bali and developed the “Bali Principles of Climate Justice”. In 2004, several groups and networks that had long been working on a critique of market mechanisms, in general, and emissions trading, in particular, came together in Durban, South Africa, and founded the “Durban Group for Climate Justice”. A final breakthrough was made at the 13th climate conference in Bali in 2007. The alliance of critical organizations mentioned above provoked an open conflict with the politically more moderate “Climate Action Network”, whose schmoozy lobbying strategy had meanwhile turned out to be quite a flop. The “Climate Justice Now!” network emerged from this 2007 conflict.

The press release announcing the establishment of this new network articulated a number of demands that still guide the climate justice movement to this day, and was later converted into a kind of founding manifesto. It demanded, first, that fossil fuels be left in the ground and investment instead focus on adequate, safe, clean and democratically-controlled renewable energies; second, that drastic reductions of wasteful over-consumption be undertaken, especially in the Global North, but also with reference to the elites of the Global South; third, that massive financial remittances take place from the Global North to the Global South based on the concept of climate debt repayment and under democratic control; fourth, that resource conservation be based on human rights, including the enforcement of Indigenous land rights and the promotion of Indigenous community control over energy, forests, land, and water; and fifth, that sustainable, smallholder farming and food sovereignty be promoted and protected. To achieve these goals, the “climate justice” movement makes use of a wide range of tools, from preparing research reports and everyday political work in communities particularly affected by climate change, to civil disobedience in the form of coal mine blockades or the militant struggles of the Ogoni in the Niger Delta.

To sum up, the climate justice movement is a descendant of the environmental justice movement. Like the latter, it originated in the Global South and focuses less on technical fixes than on the transformation of social structures. If I tried to define it, I would say climate justice is less an objective to be achieved—that is, a fair distribution of the costs of solving the climate crisis—than a process: namely the process of fighting the very social structures that cause climate injustice. If this broad definition is taken seriously, then a good deal of the struggles that currently fall under the banner of “climate justice” can actually be recognized primarily as struggles for land, water, and other basic needs, and—ultimately—for human rights.

[1] Kenny Bruno, Joshua Karliner, and China Brotsky, Greenhouse Gangsters vs. Climate Justice (San Francisco: Transnational Resource and Action Center, 1999).