The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has been a linchpin of China’s foreign policy since 2013. The Initiative aims to promote connectivity among the economies of Asia, Europe, and Africa by building networks of roads, bridges, railways, ports, airports, energy pipelines, and other forms of physical infrastructure, within which China is envisioned to be the centre. Although the Initiative primarily focuses on physical infrastructure, it is also designed as a means to deepen policy, trade, financial, and people-to-people connectivity. By 2019, over 60 countries were participating in the BRI, and China had reportedly invested approximately 127.7 billion US dollars into different projects, turning the BRI into the biggest infrastructure development plan in history.

Le Hong Hiep is a Fellow at the ISEAS—Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore.

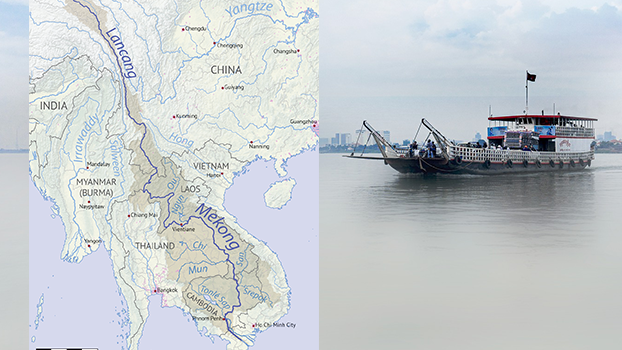

The Lower Mekong region, which includes the countries of Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam, exhibits high demand for infrastructural investment due to the region’s fast-growing economies and the overall lack of modern infrastructure. The BRI has therefore drawn great interest from these states. For its part, China considers the region one of the primary targets for the BRI, given its geographical proximity as well as China’s wish to improve connectivity between its southern provinces and Southeast Asia.

Although all five countries have officially endorsed the BRI, their actual positions on the Initiative vary. While Laos and Cambodia heartily embraced BRI projects, Vietnam has been wary of the Initiative. Meanwhile, although Thailand and Myanmar are adopting some major projects under the BRI banner, their actual implementation has faced setbacks and delays. Apart from conflicting economic and political considerations arising from the respective country’s domestic circumstances, external factors—including China’s geostrategic calculations and deepening US-China great power competition—are making it increasingly challenging for states in the region to strike a balance between realizing their infrastructural development aspirations and maintaining strategic autonomy.

Myanmar

The BRI’s flagship project in Myanmar is the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC), which includes four major components. The first is a high-speed railway running from Yunnan Province in China through Muse and Mandalay to Kyaukpyu in Rakhine State. This rail link will be built along gas and oil pipelines that were completed in 2013 and 2017. The second is the Kyaukpyu deep-water port at the southern end of the rail link on the Bay of Bengal. Together with the rail link and the pipelines, this port will give China direct access to the Indian Ocean, thereby mitigating its dependency on the Malacca Straits. The third is the construction of a “new city” near Myanmar’s former capital Yangon. The fourth is the establishment of a “Border Economic Cooperation Zone” spanning the two countries’ border at Muse in northern Myanmar and Ruili in southern China.

The two countries signed agreements to prepare for the implementation of these projects during Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit to Myanmar in January 2020. However, details such as financing arrangements and bidding procedures were left open to future negotiations. It should be noted that, in August 2018, Aung San Suu Kyi’s government successfully negotiated with China to scale down the Kyaukpyu port project from the 7 billion US dollars the previous military government had agreed to in 2015 to 1.3 billion. No major work on the CMEC had begun by September 2020, although a number of feasibility studies on component projects had been conducted.

The slow progress of the CMEC and Naypyidaw’s decision to scale down the Kyaukpyu port suggest that while Myanmar is interested in BRI projects to improve its infrastructure and promote economic development, it is also careful not to become over-reliant on China. Myanmar’s decision in 2011 to suspend the Myitsone Dam, a 3.6-billion-dollar project backed by the China Power Investment Corporation, is also a stark reminder of how BRI projects may end up in the future.

Thailand

The BRI’s cornerstone project in Thailand is the 873-kilometre high-speed rail (HSR) line linking Bangkok and Nong Khai on the border with Laos, which will form part of the Kunming–Singapore rail link. Yet this project has been delayed multiple times as the two sides could not agree on financial and technical terms. In September 2019, however, the deputy spokesperson of the Thai government said that plans were on track for the first phase, and the 252-kilometre stretch from Bangkok to Nakhon Ratchasima would start by 2023. Surprisingly, the Thai government decided to bear the entire cost of the first phase, which amounts to 5.8 billion US dollars, meaning it turned down China’s financing offer. Although work on the first section of the project (3.5 kilometres from Klang Dong to Pang Asok) had started by September 2020, the status of the remaining sections remained unclear along with China’s involvement in the project more generally.

China is also proposing other major infrastructure projects in Thailand, such as the construction of the Kra Canal connecting the Andaman Sea and the Gulf of Thailand, or the establishment of a cross-border special economic zone (SEZ) and logistics hub in the northern city of Chiang Rai. While Thai stakeholders are opposed to the SEZ plan in Chiang Rai, the prospects for the Kra Canal project also appear dim after the Thai government publicly endorsed the construction of a land bridge instead of a canal in September 2020. Should the proposed Kra Canal ultimately be scrapped, it will deal a major blow not only to the BRI but also to China’s strategic ambitions, as the canal has long been expected to help Chinese merchant and military ships bypass the Malacca Straits. For now, it appears that the Thai government is more interested in building the Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC), which will leverage private investments rather than government-to-government loans under the BRI. Although Chinese companies have expressed interest in investing in the EEC, their participation in this major project has not been confirmed yet.

Like Myanmar, Thailand adopts a rather prudent approach to the BRI, mainly out of commercial considerations. The slow progress of the Bangkok–Nong Khai HSR project was particularly frustrating for China. However, given the rather friendly relationship between the two governments and the large number of Thai conglomerates with strong ties to China, the BRI may still have positive prospects in Thailand. For example, although the implementation of the EEC will be led by Thai private investors, there is a high possibility that these investors may choose to work with Chinese creditors, suppliers, and contractors to implement the project.

Laos

The most important BRI project in Laos is the 411-kilometre railway connecting Vientiane with the northern town of Boten on the border with China. The construction of the railway, which will also form part of the Kunming–Singapore rail link, costs 5.9 billion US dollars—more than one third of Laos’s GDP. Almost the entire cost will be covered by loans from China Eximbank, a state-led institutional bank tasked with promoting the export of Chinese products and services. The project began in December 2016 and is currently on track to be completed and open to traffic in December 2021.

In addition to the railway , China has also invested in some power development projects, most notably a cascade of seven dams on the Nam Ou River, a major tributary of the Mekong. These dams, with a total investment of 2.733 billion dollars, are being developed by PowerChina in two phases. Phase I, including Nam Ou 2, Nam Ou 5, and Nam Ou 6, started operation in May 2016. Phase II, including Nam Ou 1, 3, 4, and 7, is expected to be completed in 2020.

Laos has been a strong proponent of the BRI, evidenced by its adoption of the Vientiane–Boten railway project despite its high cost and associated financial risks. Although the project has progressed well, there have been concerns that Laos will not be able to service its debts to China. In early September 2020, Laos reportedly ceded a controlling stake in its national electric grid company, Electricite du Laos Transmission Company Limited (EDLT), to China Southern Power Grid Co. This gave rise to concerns that Laos was falling into China’s “debt trap”. The World Bank estimated that Laos’s debt levels would increase from 59 percent of GDP in 2019 to 68 percent in 2020. Meanwhile, rating agency Moody’s warned of “a material probability of default in the near term”, noting that Laos’s debt service obligations in 2020 were around 1.2 billion US dollars, while in June 2020 its foreign reserves were just 864 million. This is a worrying sign for both Laos and China, for if Laos defaults, its economic growth and political autonomy will suffer, while another example of “debt-trap diplomacy” will further undermine the reputation of China as well as the BRI.

Cambodia

Cambodia is one of China’s main BRI partners in Southeast Asia. Cambodian Minster of Public Works andTransport Sun Chanthol revealed in early 2018 that “more than 2,000 kilometres of roads, seven large bridges, and a new container terminal at the Phnom Penh Autonomous Port had been constructed with support from China”. Some major infrastructure projects which started before the BRI have also been rebranded as part of BRI. Among them is the 1,113-hectare Sihanoukville Special Economic Zone, established in 2008 with Chinese investments worth 610 million dollars.

Some other notable projects include the 190-kilometre Phnom Penh–Sihanoukville Expressway to be built by the Chinese Communications Construction Company Ltd. with a total investment of 1.9 billion US dollars, Kandal Airport to be constructed by a local conglomerate with 1.1 of the 1.5 billion US dollars in investment financed with Chinese loans, and Cambodia’s plan to launch its first communications satellite in 2021 through a joint projectbetween a local conglomerate and the China Great Wall Industry Corporation.

The most notable BRI project in Cambodia is arguably the 3.8-billion-dollar Dara Sakor investment zone, which is controlled by a Chinese company that holds a 99-year lease. Encompassing 20 percent of Cambodia’s coastline, the zone features an international airport, a deep water seaport, industrial parks, a luxury resort, power stations, water treatment plants, and medical facilities. As of September 2020, construction of various projects in the zone was still ongoing, while the Dara Sakor Resort had opened to tourists. The project has triggered some protestsinside Cambodia as well as security concerns for other countries, especially the United States. US officials suspect that the runway and sea port facilities at Dara Sakor are intended to serve China’s military purposes. In September 2020, the US sanctioned the Union Development Group (UDG), the project’s Chinese project developer, for “seizure and demolition of local Cambodians’ land”. Strategic competition with China appeared to be the main motivation behind the US sanctions.

Cambodia strongly supports the BRI not only because of its own economic interests, but also because Beijing has provided political support for Prime Minister Hun Sen against international pressures concerning his authoritarianism and poor human rights records. Cambodia’s decision to develop BRI projects through private companies rather than government-to-government loans may also reduce the debt-trap risk. At the same time, adopting large Chinese infrastructure investments may eventually constrain Cambodia’s strategic autonomy and lead to its economic dependence on China. The US sanctions on UDG also suggest that Cambodia may be dragged into the intensifying strategic competition between the US and China should it allow BRI projects to be used to advance Chinese military ambitions in the region.

Vietnam

Among the five countries, Vietnam is the most cautious about the BRI despite its enormous need for infrastructure investment. Although Vietnam endorsed the BRI as well as the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), it has been reluctant to apply for BRI projects. As of September 2020, only one loan of 250 million US dollars issued in 2017 for the Cat Linh–Ha Dong metro line in Hanoi, which began construction in October 2011, was unofficially considered to be part of the BRI by both Vietnam and China. At the same time, China also unilaterally classified the 1,200-megawatt Vinh Tan 1 coal-fired power plant in Binh Thuan province as a BRI project. The plant was completed in 2018, and 95 percent of the more than 2 billion dollars in total investment was funded by a Chinese consortium.

Vietnam’s reservations about the BRI can be explained by three factors. Firstly, Vietnam has had a number of negative experiences with Chinese-funded infrastructure projects, including shoddy construction, project delays, and cost overrun. A primary example is the Cat Linh–Ha Dong metro line, which had not been put into operation by September 2020 folllowing multiple delays. Secondly, Vietnam found the commercial terms and conditions of Chinese loans unattractive and can access other funding sources for its infrastructure projects, such as loans from ODA partners and multilateral creditors or private investments. Finally, Vietnam was concerned about the strategic implications of the BRI in the context of the South China Sea dispute, as accepting Chinese loans will undermine Vietnam’s strategic autonomy and make it more difficult for Hanoi to stand up to Beijing’s maritime coercion.

Different Experiences, Different Paths

The above profile of the BRI in the Lower Mekong region suggests that states in the region have adopted different approaches to the initiative based on their perception of threats and opportunities that the BRI offers. While Laos and Cambodia see more opportunities than threats, the South China Sea dispute and Vietnam’s unique experience of resisting repeated Chinese invasions throughout its history cause it to be highly wary of the BRI. Thailand and Myanmar find themselves somewhere in the middle, more open than Vietnam but less enthusiastic than Laos and Cambodia in considering BRI projects.

Such perceptions will continue to evolve in the future depending on how much benefit BRI projects can actually bring countries in the region, and whether economic and strategic risks associated with such projects will materialize or not. China’s ability to sustain the BRI amidst rising economic challenges and plans by the US and its allies to discredit the BRI will also be critical. If China can continue to deliver its promises while the US and its allies fail to offer alternatives to the BRI, the current dynamic will continue and China will enjoy a degree of economic and strategic preponderance in the region. Otherwise, neighbouring states will regard it a matter of national interest to moderate their approach to the BRI and maintain a fine balance between the two great powers.