The “Belt and Road Initiative” has been widely discussed among Chinese intellectuals and academia since its outset. Indeed, through different stages, these discussions distinctively shaped the form, substance, and direction of what is now understood as one of the biggest infrastructure projects in human history.

When President Xi Jinping first proposed a “New Silk Road” during a speech given in Kazakhstan in 2013, it was neither a project nor a programme—initially, it was merely an idea and a possibility. Yet the idea was quickly picked up, and the term “One Belt, One Road” soon penetrated Chinese academic, political, and public discourse.

Dr. Junyan Wang is a project manager at the Beijing Office of the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung, whose PhD focused on China’s rural development. The primary focus of her work is theoretical and empirical research on socialism with Chinese characteristics and ecological civilization.

Dr. Jan Turowski is the Head of the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung’s Beijing. From 2013 to 2019 he was a Professor of Political Science at Southeast University in Nanjing. He works on, among other topics, socialism and transformation research.

At first, the terms “Silk Road” or “One Belt, One Road” were highly abstract, almost empty phrases. This is in fact quite typical of Chinese politics: new political terms or slogans are usually introduced as almost too broad and abstract for any kind of political programme. When such political terms are initially presented, the Chinese government usually intends to provide as little specific information as possible about what they actually mean. However, this vagueness often creates space for lively debate in academia, the media, as well as among the general public.

Most concepts initially only offer points of departure and broad visions for discussion—they are not yet comprehensive and complex political programmes. In fact, what form the concepts eventually take depends on the discussions and contributions of scientists, experts, and policy makers who develop concrete ideas for implementation and seek to further substantiate their content. To this end, universities, research institutes, think tanks, and various branches of central government as well as provincial governments are encouraged by the Chinese leadership to hold workshops and conferences at various levels throughout the country in order to stimulate and refine the debate.

Against this backdrop, the “Belt and Road Initiative” has been discussed—with different emphases during different phases, of course—broadly along three sets of questions:

- Why is China proposing a “Belt and Road Initiative”, and does China need such an initiative at all? What are its concrete projects, mechanisms, and policies? Particularly in the forums organized in different Chinese provinces, many local cadres added stronger domestic, localized, and socio-economic dimensions to the project.

- What are the challenges, problems, and risks?

- And finally, what new perspectives and concepts ought to be linked to the initiative?

These questions were discussed alongside various criticisms and claims from abroad which had entered the Chinese debate. Generally speaking, the debate gradually developed from “one initiative” and “grand vision” to various realistic and practical cooperation strategies, plans, and projects, growing increasingly empirical and dense as institutional frameworks were established, cooperation mechanisms and platforms constructed, projects implemented, and “Belt and Road Initiative” research institutes and think-tanks opened across the country.

Research related to “Belt and Road” has gradually increased as a result. According to statistics, from 2014 to 2018 the number of Chinese periodicals on this topic increased year by year, reaching a peak in 2017 with about 3,500 articles.

Why “Belt and Road”?

Why did China propose the Belt and Road Initiative in the first place?

President Xi Jinping did not propose the idea of a “New Silk Road” in a vacuum, the BRI developed within a specific context. However, there was only one article in 2016 that mentioned any direct considerations retrospectively. [1] According to this article, on the basis of experiences with the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and the Eurasian Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs had been planning to integrate a series of cooperation initiatives put forward by related Asian countries, and gradually formed the idea of building a new Silk Road.

After the Chinese government officially proposed the Belt and Road Initiative in 2013, Chinese scholars analysed China’s international and domestic situations and factors that initially formed the government idea for such an initiative from various angles, including:

- geopolitics, especially the US “New Silk Road Strategy” in Central Asia and the “Indo-Pacific Rebalancing Strategy”;

- The 2008 global financial crisis and its impact;

- China’s rise and the shifting international order;

- the legacy of internationalism and the Bandung Conference;

- China’s experiences with cooperation at the regional level, such as BRICS, ASEAN, SCO, and China-Africa Cooperation;

- China’s own development experience and challenges in the process of globalization.

It is safe to say that all of these factors collectively contributed to China’s decision to launch the BRI. In this process, lasting roughly from 2014 to 2018, one task facing Chinese scholars was to explore and try to define the essence of the Initiative, while also taking Western criticism, which accused China of “neo-colonialism”, “resource capture” and instituting a “debt trap”, into account. For instance, Ma Yan from the Shanghai University of Finance and Economics constructed a mathematical model of “inverse inequality”, demonstrating the BRI’s role in reducing international inequality rather than promoting neo-colonial dependency.[2] Zhong Feiteng of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences emphasized that many Western articles on the BRI focus solely on China’s intentions, while ignoring the level of development and needs of countries set to be linked through “One Belt, One Road”.[3]

From 2015 onwards, the debate shifted decisively towards detailed and rather empirical research questions, bi- or multilateral frameworks, and a focus on institutions and mechanisms, concrete projects, countries and regions, actors and interests.

At the same time, scholarly debate in China around the definition and purpose of the Belt and Road Initiative along with Western doubts and criticism initiated new reflections on globalization itself. Many scholars emphasized that the Belt and Road Initiative is a new type of globalization that transcends neoliberal globalization by being more inclusive, balanced, and sustainable. It does so by effectively balancing the role of the government and the market and emphasizing cooperation between governments to provide public goods rather than relying solely on the market and unfettered multi-national corporations. This further breaks the Western-dominated “centre-periphery” hierarchy and helps to overcome the power imbalance between maritime and landlocked countries, forming an open network of common development through interconnections.

Where to Go from Here?

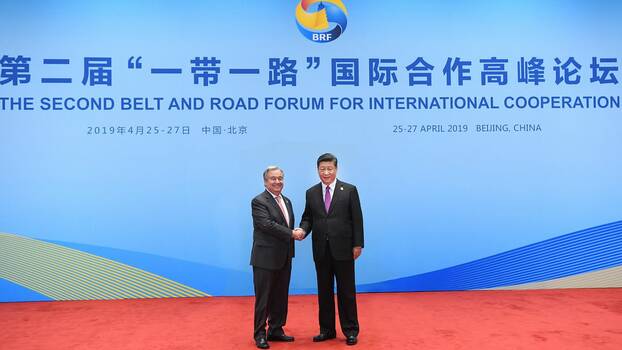

As a practical platform to promote the construction of a new type of international relations, the Belt and Road Initiative has attached high importance to cooperation with international organizations represented by the United Nations. In November 2016, the BRI was included in United Nations General Assembly Resolution a/71/9 for the first time, calling on the international community to provide a safe and secure environment for the Initiative. Many Chinese scholars reflected on China’s cooperation with the United Nations and proposed conceptual coupling of the BRI with the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Specific to the field of ecology, Huan Qingzhi from Peking University believes that China’s active implementation of the BRI could be a vehicle for creating, disseminating, and demonstrating a global resource- and environmental security culture.[4]

In the process of advancing the construction of the Belt and Road Initiative, China has implemented the “Green Development Concept”, built a “Green Silk Road”, and continuously improved the “Green Belt and Road” policy system. In 2019, the “Belt and Road Initiative International Green Development Coalition” was established. It is organized within the Chinese Ministry of Ecology and Environment, which—in collaboration with five other Chinese government departments—issued the “Climate Finance Guidance”, including a timeline for having relevant policies for investment ready by 2025, and more importantly states that China aims to “regulate offshore investment and financing activities” and manage climate risks abroad.

Concern and Scepticism

On the whole, Chinese scholars hold a positive attitude towards the initiative. That said, some scholars have expressed worries and criticisms. Shi Yinhong from Renmin University of China argued that China’s foreign strategy has undergone a major shift since 2014, specifically from “strategic military” to “strategic economic”.[5] In his eyes, China ought to cultivate political and strategic prudence in advancing the BRI. A great deal of importance should be attached to clearly defined and shared visions and the fair distribution of benefits among the countries along the New Silk Road.

With regard to doubts, worries, and criticism from other countries, careful investigation and study should be carried out to examine the extent to which they are justified and how to deal with them reasonably. The advancement of the Belt and Road Initiative should be carried out in stages and should not focus on the economic, trade, and investment dimensions alone, but should also pay attention to the social, cultural, and educational dimensions. In this sense, China’s strategic efforts must be based on thoughtful tenacity.

[1] Zhao, Kejin (2016): “Research in ‘One Belt and One Road’ and China Strategy”, in: Journal of Xinjiang Normal University(Philosophy and Social Sciences) No.1: pp. 23–31.

[2] Ma, Yan et. al (2020): “On the Reverse Inequality Effect of the Belt and Road Initiative: Refuting China’s ‘Neo-colonialist’ Questioning”, in: World Economy No. 1: pp. 3–20.

[3] Zhong, Feiteng (2017): “‘One Belt and One Road’, New Globalization and Relations between big countries”, in: Foreign Affairs Review No.3, Page 1–25.

[4] Huan, Qingzhi (2019): “The Construction of Global Resource and Environment Security Culture from the Perspective of a Community of Shared Future for Mankind”, in: Pacific Journal 27, No.1: pp. 1–8.

[5] Shi, Yinhong: «One Belt and One Road». Wish for Caution, in: World Economics and Politics, Nr. 7 (2015), S. 151-154.