Since the 1980s, women from rural parts of Senegal have migrated to large cities to enter the domestic labour market. There are many causes driving them to leave the countryside to work as domestic workers in cities. As domestic workers, no social security coverage is available to them. They are left at the mercy of a capitalist system that slowly kills their prospects for the future and increases their suffering under a social and economic system that overshadows them. Indeed, their workloads are growing day by day in return for a degrading income in the face of ever-increasing economic inflation.

These domestic workers form a considerable but informal economic mass that no economic strategy takes into account. They are victims of twofold asymmetrical discrimination: both economic and social discrimination and discrimination due to being women. Consequently, the gendered division of labour accentuates the feminization of poverty.

Fatou Faye works as a Programme Manager for Senegal at the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung’s West Africa Office.

This text discusses the legal framework for domestic labour in Senegal, including both national and international legislation and conventions, and the problems to implementation. It then expounds upon the living and working conditions of domestic workers in Senegal, highlighting some of the many problems they face. Lastly, the text analyses attempts at organizing domestic workers through unions and other associations.

The Legal Framework

Senegal has ratified all UN conventions that protect human rights. The Senegalese constitution also denotes them as integral components thereof in its preamble. On the basis of this consideration, Senegal has also signed and ratified all the International Labour Organization conventions.

Even prior to ILO Convention 189, Senegal’s Order No. 0974 dated 23 January 1968 established the general terms of employment of domestic workers and housekeepers, providing their legal classification. Ranging from the classification of the types of employment for domestic workers to the obligations of the employer, Senegalese legislation has provided for an expertly arranged professional framework for the domestic labour market. Wages and their evolution are well defined in this law.

However, the law suffers from non-effectiveness, it is not enforced and there are no denunciations or sanctions for its violation. At the same time, the law is not sufficient because it does not take into account the rate of inflation and rising cost of living in large cities when calculating the minimum wage for domestic workers.

Senegal’s New Domestic Paradigm

Domestic work—a profession that is feminized and nourished by informal system with its share of injustices—is especially popular among women from rural backgrounds. The domestic work of these “migrant” women helps strengthen the gendered division of labour: this socio-professional category sells services to the middle class of Senegalese society. Despite the many difficulties these domestic workers face in cities, some of them are resolutely fighting against the injustices they face.

Once in the cities, domestic workers are confronted with situations that degrade human dignity. Indeed, the majority of Senegal’s cities, especially Dakar, are witnessing a massive influx of young people from the countryside. In search of work in a household, these young women, often lacking proper academic or vocational training, tend to sell their services for low wages. In the places of departure, the causes that drive them to become domestic workers are numerous. Indeed, the scarcity of rain, the lack of modernization of agriculture, poverty, unemployment, and lack of institutional response to social and economic needs are all characteristic of a rural Senegal that does not offer young people a real future. This is without mentioning other social realities—such as divorces, repudiations, lack of a stable educational background for girls—which directly undermine women’s empowerment in the countryside, whereas in some local cultures they represent the guarantors of family food resources. With the deterioration of the economic and social situation in the countryside, women are also being pushed to leave for the city.

When they arrive in large cities, those who do not have family or another place to stay sleep in groups in the streets. Others are welcomed by an uncle, an aunt, or other acquaintances during the time it takes them to find a job to be able to take care of themselves (pay for food, rent, electricity, water, etc.).

It is by knocking on doors every day, meeting in different intersections around the city, that, upon recommendation, these women can find employers to hire them. They are employed for a salary that varies according to age, experience, maturity, body size (female employers are most likely to recruit workers deemed “uglier” so as not to risk their spouses growing attracted to the domestic help), and the tasks to be completed on a daily basis. Domestic workers who are “lucky” enough to meet all the conditions according to the employer’s tastes receive a “salary” that usually ranges from 75,000 to 80,000 CFA francs per month, on the understanding that any damage done to the employer or their property (e.g. short-circuiting household appliances) will be withdrawn from the employee’s monthly income.

There are no studies on the numbers of domestic workers who are incarcerated as a result of being charged with theft by their employer. Indeed, many domestic workers are the first to be charged in the case of workplace theft. This leads to abusive incarceration of domestic workers, who often do not have the means to access a lawyer. Even before they are exonerated in most cases, they are first victims of a warrant of committal that violates their dignity without any reparation in return.

Domestic workers are only hired through a simple tacit contract that does not include a declaration to the social security fund, annual, weekly, sick, or maternity leave, or guaranteed medical care (while domestic accidents are recurrent and the tasks themselves are physically draining), with a workday that can exceed 13 hours per day. The whole thing is crowned by unfair dismissals without notice, made possible by the absence of binding legal contracts. It is a profession in which all duties weigh on female workers who have no contractual protection in return. Nevertheless, these domestic workers tighten their belts so that their meagre incomes can ensure a respectful place in their village through the financial assistance they provide to their children and their families in the village (buying food, acquiring land, renovating family homes, sending parcels for important holidays, caring for children, buying seeds for the husband’s fields if he stayed in the village, etc.).

The lack of value placed on domestic work has rendered the women who engage in it as a fragile social category at the bottom of the social scale. They replace women in cities in certain household roles that are radically affected by their customs, which are preserved by a ruthless social gaze that judges women according to how they cope with domestic tasks. Urban women must ensure that these domestic tasks are carried out, but they often have neither the desire nor the time. That is why they use domestic workers. According to woman who has worked as a domestic worker in Dakar for eight years and is a member of a domestic workers’ organization:

If women are able to work with their heads rested in their offices, it is thanks to us domestic workers. They cannot perform the function of a housewife and their professional activities at the same time. So the more intellectual women who have access to employment, the more domestic workers are needed as well, because they are theones who employ us. Beyond sexual harassment often resulting in unwanted pregnancies and children who are not recognized by their progenitors, some women employers—not all—are also the source of all the injustices we suffer. It is difficult to say but it is pure reality.

At a time when hundreds of millions of francs are being spent on conferences and panels by women’s organizations for the respect of women’s rights in accordance with the international conventions ratified by Senegal, some women seem invisible. They are always there, often going beyond the tasks that were originally entrusted to them and with all that this can involve psychologically (soothe the bad moods of the employer, sometimes substitute for the role of mother, prepare meals, take care of houses, children, etc.), but they seem transparent to the people for whom they perform all these services.

According to Ndèye Khoudia Ba, a Senegalese psychologist based in Toulouse, “this situation experienced by domestic workers is both economic and psychological violence that in the long run causes victims to sink into unprecedented bitterness; hence the symptoms of a sensitivity to the skin, i.e. to respond in a very negative and violent way against the perpetrator of these injustices. The lack of respect they are sometimes subjected to in their workplace undermines their dignity and creates a psychological imbalance: they no longer trust in their society, in these mechanisms of communication, protection…” [1]

The Evolution of Domestic Employment

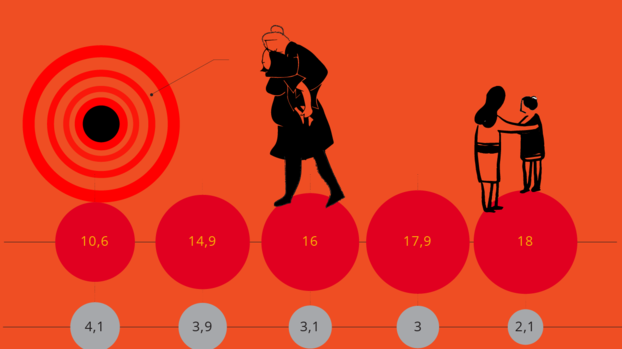

Domestic employment is evolving in a way that is leading to more disastrous horizons. Over the last decade, the supply of domestic work has far outstripped demand, leading to a systematic reduction in the wages offered by employers. Additionally, competition from foreigners (often Guinean and undocumented minors), who accept all the employers’ demands and will work under any conditions, makes the situation more difficult because employers abuse those workers’ vulnerability, employing them through the informal market without providing workers with any legal protections, and, in some cases, engaging in child trafficking.

Furthermore, job seekers in this market are becoming younger and younger, as underage girls (between 14–17) are very likely to be hired because they can be paid less. Unlike the situation of yesteryear, these young girls are hardly illiterate. Indeed, they drop out of school (mostly college) to join their mothers, aunts, or sisters who also work in the domestic labour market. Therefore, classification no longer only occurs by qualification segment, need, or circumstances, but evolves according to family segment. Some of these young domestic workers are also looking at other horizons that push them to migrate to Maghreb countries to benefit from higher incomes, but with much more precarious working conditions (passport confiscation, physical and verbal abuse, rape, etc.). This migration takes place clandestinely in a system that is well-organized by smugglers.

Empirical research also evidences the exploitation of young boys from certain countries bordering Senegal (Mali, Guinea) in the domestic labour market with the complicity of their parents. These young minors mainly work in residential sites and their income is paid directly to their parents. The exploitation of these children is increasing, despite the warnings of local non-governmental organizations. While these children are aware of the exploitation and sometimes revolt, they are severely repressed by their parents.

Over the past seven years, agencies have been set up to better organize the domestic labour market. However, much is unclear about these agencies’ practices. They are responsible for finding an employer for women who want to sell their service as a domestic worker. In return, 10 or 20 percent (depending on the agency) of the worker’s first salary will be entitled to the agency. However, there are no contracts for domestic job seekers, and there are many questions they refuse to answer. For example: in the event of violence against the domestic worker by the employer, what will the agency’s role be? In the event of non-payment of the domestic worker’s income, what will the agency do? Does the agency conduct morality surveys on employers before assigning them a domestic worker?

The Impact of COVID-19

While the situation for women domestic workers was already precarious before the pandemic, their situation has now worsened considerably. They were the first to be impacted by the health emergency caused by COVID-19. Indeed, before curfews and confinements were on the agenda, domestic workers were unfairly dismissed because employers believed that “domestics” were the only vehicles that could contaminate them, because they use public transport, live in slums, and operate in precarious situations.

This rejection has created a great sense of frustration for domestic workers. Overnight, they lost all of their wages and were not prepared for the containment measures. The economic recovery plan deployed by the Senegalese government did not mention domestic workers in any way. Most have not been able to return to their former positions. The direct consequence of this is that some have turned into beggars while they wait to find another employer; the indirect consequence is that their families who remain in the village are affected (children forced to abandon school, dislocation of their families).

Networks, Unions, Organization

The intervention of women’s organizations and NGOs for the protection of domestic workers has been rather timid. There are television programmes and seminars that denounce the precariousness in which these women operate, but these have not led to decisive action. Of course, this effort to increase the civil society recognition of domestic work is not negligible because it has enabled the formation of an organization among domestic workers in association.

Senegal participated in the preparatory work for the organizer’s manual to promote ILO convention no. 189. This document has been made available to all Senegalese trade unions. But its implementation is lacking due to a lack of strategies and resources, although some trade union centres are trying hard to come to grips with it.

The National Union of Autonomous Trade Unions of Senegal (UNSAS) is the only Senegalese trade union that has attempted to integrate domestic workers into its organization following the recommendations of the International Labour Organization in 2012.

Formalized in 2019, the Association of Women Domestic Workers of Senegal is facing problems of a lack of means to carry out its actions and its policy oriented toward raising public awareness of these women’s working conditions, as well as to organize legal actions in cases of abuse suffered by its members. Currently, the association is limited to training sessions about labour law, how to use certain household appliances, and meetings with financial partners for project proposals.

In 2021, the association is participating in a study on the situation of domestic workers in Senegal with the support of the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung’s West Africa Office. The purpose of this study is to elaborate on the causes that motivate women to leave the rural world to become domestic workers in large cities. The study will also address the sociological aspects of the issue. The study’s final document will provide unions and associations with a qualifying and quantitative estimation tool using specific data in order to be able to conduct advocacy with state authorities.

Convinced that they can correct these injustices, Senegal’s domestic workers’ union, which has been affiliated with the National Union of Autonomous Trade Unions of Senegal (UNSAS) since 2008, with the support of Committee 12 12 (Special Monitoring and Warning Committee, which brings together representatives of the five trade union centres in Senegal for the ratification of Convention 189 and the implementation of ILO Recommendation 201), calls for ratification of the International Convention on Domestic Workers (ILO). Selon Ndella Diouf, general secretary of this union, states:

We have always been aware of what we are experiencing as violence, injustice, and stigma. But we lived in constant fear of losing our jobs. Now there is a collective awareness about the precarious conditions in which we work with our meagre wages. This awareness is a very important step for us in order to be able to concretely identify the problems that we face from near or far as domestic workers. Now we are trying to establish a significant number and seek to rally the masses of domestic workers so that our voices will carry because we want a massive membership of female workers. Here we go to some debates on the radio to talk about our working conditions in the public square. We organized marches with UNSAS in front of the National Assembly of Senegal to raise awareness among women MPs on the issue and we had meetings with former Labour Minister Mansour Sy. But after the appointment of the new minister, Samba Sy, we feel like we are starting all over again in negotiations with the state. We know that we will be the only ones to hear the cause for which we are fighting.

We have not only the state as an interlocutor but also any force that can help us by agreeing to listen to us because we are the employees of these political authorities who say they want to defend the nation while we suffer an injustice in their own homes. It is contradictory, isn’t it?

We now want our employment to be established by an employment contract so that we can benefit from all the rights of a worker worthy of the name to do so with our low wages. We are a considerable economic burden for both the city and our villages that we have left. We try to meet according to a quorum whenever one of us has a problem with her employer and we try to find a solution for them in solidarity. What we must avoid is isolating ourselves, which is why we invite all our sisters to join us in defending our common cause.

The domestic labour market suffers from many injustices that disadvantage the women who work in it in Senegal. However, through more organization and advocacy with respect for human rights, the actors of the domestic labour market can improve their conditions and have more respect in society.

[1] Ndeye Khoudia, The Mental Health of Domestic Workers in Senegal: Case Study, Ph.D. thesis at Cheikh Anta Diop University, Department of Sociology, 17 July 2004.