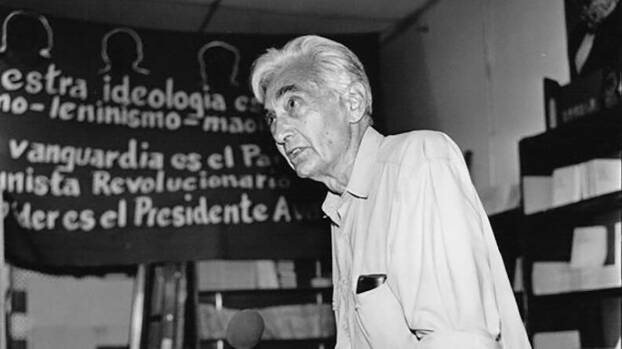

Few historians of the United States have proven as influential as Howard Zinn, who was born 100 years ago today on 24 August 1922. Yet while millions of progressive and even liberal Americans know and admire his work, he was and continues to be largely ignored by academics. No doubt, Zinn himself would be thrilled that his books are still considered helpful in understanding America’s past and laugh at the so-called “real” historians who disregard him — after all, compared to Zinn, their books are read by only a tiny fraction of the population.

Peter Cole is Professor of History at Western Illinois University and Research Associate in the Society, Work and Development Institute at the University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa, as well as the founder and co-director of the Chicago Race Riot of 1919 Commemoration Project. His most recent book is Dockworker Power: Race and Activism in Durban and the San Francisco Bay Area (University of Illinois Press, 2018).

A prolific writer, Zinn is best-known for his magisterial A People’s History of the United States: 1492–Present. First published in 1980, more than one million copies have been sold, and it remains in print to this day. A People’s History entered American popular culture in the 1997 film Good Will Hunting, when actor Matt Damon recommended Zinn’s book to a nemesis. It inspired numerous side-projects, including Voices of a People’s History of the United States (2004), A Young People’s History of the United States (2007), and A People’s History of American Empire: A Graphic Adaptation (2008) by Mike Konopacki and Paul Buhle.

Zinn practiced what is known as “history from below”, centring the lives of ordinary people in telling the history of the United States. He belonged to a generation of historians in the 1960s who challenged the “Consensus School” of US history which dominated in the Cold War era and claimed that Americans were one, united people, and obfuscated class, gender, racial, and other conflicts that had divided US society since its inception. Zinn was not a “child” of the 1960s, but rather of the so-called “Greatest Generation” of Americans who lived through the Great Depression and World War II. But Zinn was always ahead of his time. Indeed, he still is.

A Career in the Struggle

Howard Zinn was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1922 to Jewish immigrants who met while working in a factory. In the 1930s, Communist friends invited Zinn to a political rally, where he witnessed police beating peaceful marchers. This experience profoundly impacted the teenager.

Zinn completed high school in 1940 after World War II broke out in Europe and began working at a shipyard, where he got involved in union organizing. Proudly antifascist, he enlisted and became a bombardier in the US Air Force. His unit was involved in many bombing raids in Europe, including the dropping of napalm in France very late in the war, which he later described in The Politics of History (1970). For the rest of his life, he questioned the legitimacy of wars and the complicated ethics of being a soldier.

Along with eight million other military veterans, Zinn benefited from the GI Bill, which paid for his undergraduate studies at New York University, graduating in 1951. He earned his M.A. and Ph.D. in History from Columbia University.

Zinn taught at Spelman College, a prominent, all-female, historically Black institution in Atlanta, Georgia. From 1956 to 1963, he chaired its History and Political Science department, where he was active in fighting racial segregation in the historical profession and community. He advised a number of those who formed the small but deeply significant Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in 1960. Some of the students he inspired included Alice Walker, the legendary novelist of The Color Purple, and Marian Wright Edelman, founder of the Children’s Defense Fund. He was fired in 1963, ostensibly for insubordination, but really for radicalizing his students.

The following year, he authored SNCC: The New Abolitionists (1964). About his time at Spellman, Zinn later wrote, “I learned more from my students than my students learned from me.”

Zinn was among the most prominent and earliest opponents of the US war in Vietnam. He authored Vietnam: The Logic of Withdrawal (1967) at a time when — despite growing opposition — most Americans still supported the war and denounced anti-war protesters as “traitors”. In 1968, he travelled to North Vietnam with several radical Catholic priests and secured the release of three American prisoners of war.

Zinn collaborated with Noam Chomsky to edit the Pentagon Papers (1971). Daniel Ellsberg, a government consultant turned “whistle blower”, had copied a huge number of secret government documents about the history of US involvement in Southeast Asia and shared them with the New York Times. The Pentagon Papers was the result, and Zinn and Chomsky’s version was widely read.

From 1964 to 1988, Zinn worked in the Political Science department at Boston University. Predictably, he had a chequered career, in no small part for promoting unions on his own campus and constantly questioning authority.

Zinn’s Enduring Legacy

While Zinn wrote more than 30 books, A People’s History of the United States was his most influential work. A reinterpretation of US history, the book intentionally focused on the voices and lives of the many peoples traditionally ignored in teaching the subject. It recognized that the rights of the working class, women, American Indians, African Americans, and other oppressed groups had historically been systematically denied, and could only be realized through collective struggle.

He began his book with the genocide of indigenous people, in a chapter entitled “Columbus, the Indians, and Human Progress”. Zinn noted that Columbus and other Europeans were treated with “hospitality” due to indigenous peoples’ “belief in sharing”, but they were met with greed, arrogance, and prejudice. The result was the genocide of the Arawak, Carib, Taino, and hundreds of other indigenous peoples across the Americas.

Zinn also criticized US foreign relations in the chapter “The Empire and the People”, featuring the bloody, five-year war the US military waged to deny independence to the Philippines (1898–1902). Probably the least-known war in US history, it left about 5,000 Americans and more than 100,000 Filipinos dead. He eviscerated the justifications for the US war in Vietnam in “The Impossible Victory: Vietnam”. The Mỹ Lai massacre, the carpet-bombing of Vietnam and Cambodia, and other atrocities are named.

He put capitalism on trial in countless chapters, starting with the Spanish thirst for gold, European colonists’ despoiling of lands and resources, and the exploitation of working people. He never abandoned his view that “democratic socialism” was necessary and good.

Zinn married Roslyn Shechter in 1944. They remained together until her death in 2008. They had one daughter, Myla, and one son, Jeff. Howard Zinn passed away on 27 January 2010 at the age of 87.

In 2008, the Zinn Education Project (ZEP) was launched. According to its website, “The Zinn Education Project promotes and supports the teaching of people’s history in classrooms across the country” including by providing lesson plans for teachers. ZEP provides stands at the forefront of those fighting those wishing to deny the ugly truths of America’s past.”

Today, there are myriad efforts to ban the teaching of historical facts in US schools because they make some Americans uncomfortable. Fortunately, Howard Zinn’s lifetime of activist scholarship provides us with the tools to respond to such denials and distortions and fight for a more just world.

Happy birthday, Dr. Zinn, and presente!