The constitutional process in Chile cannot be understood without reference to the popular revolt of October 2019, the event that marked the beginning of a new turning point in Chilean history. This uprising was the most explosive and persistent irruption of the popular masses into the public sphere since the national days of protest against the dictatorship in 1983.

Pablo Abufom Silva is a translator and holds a Master’s degree in philosophy from the University of Chile. He is an editor at Posiciones: Revista de Debate Estratégico, a founding member of the Centro Social y Librería Proyección, and part of the editorial collective of Jacobin América Latina, where this article first appeared.

Translated by Ubiqus translation services.

The decades-long protests against the rising precarity of life in post-dictatorial Chile, exemplified by the student, trade union, feminist, anti-colonial, and social rights campaigns that took place and coalesced between 1990 and 2019 serve as the backdrop to this outburst of rage. The sustained criticism of the Political Constitution of the Republic (drafted by a committee appointed by the dictatorship and endorsed in a fraudulent plebiscite in 1980) from the Chilean Left also bore fruit, as it managed to win a permanent place in the democratic and progressive shared consensus.

However, the deeper underlying undercurrent of the revolt, which explains the shift towards a constitutional process, is the widespread crisis in the way social reproduction is organized in Chile today, characterized by a fraying and volatile rentier economy, an excessively unequal social structure, and a political party-based system of representative democracy that is incapable of representing the new subjectivities engendered by the economic crisis, particularly new groups experiencing insecurity and exclusion.

This crisis in the organization of social reproduction in Chile explains why the country has transitioned from a phase of sectoral demands on the state to a programme of structural reform from the constitution downwards in a very short period of time. This amalgamation of the dispersed fragments was already signalled in the Programme against the Precariousness of Life, which was presented at the Plurinational Meeting of Las Que Luchan (Those that Fight) at the end of 2018, and which was also the programme of the 2019 Feminist General Strike, the most widespread mobilization of the post-dictatorship prior to the October uprising.

Those movements achieved something that the radical Left in Chile had not accomplished in 30 years: they brought together within the same democratic process all the sectors that had been fighting for decades in order to finally weave together a broad agenda for the plurinational working class of Chile. The resulting synthesized programme serves as a clear illustration of the power of feminism, a force that has accompanied several significant political movements in recent years (in Argentina, Brazil, Spain, Colombia, and the list could go on). This is the reason the constitutional process is the greatest expression of the popular revolt of October 2019, considering the degree of organization and political consciousness among Chile’s popular classes. The crisis had compelled the forging of a comprehensive programme from which there was no turning back.

All the political parties attempted to channel the fury of the revolt into a constrained institutional process, in the image and likeness of the controlled democracy of the Transition. They tried to negate the revolt, seeking to exclude the popular masses from the constitutional process. But this was not possible. The door to democratization had been forcibly thrown open by the revolt, making it possible for social movements and indigenous peoples to participate in a parity system with seats reserved for them.

The election of constituents in May 2021 revealed that the majority of the country held the Right and centre-left responsible for the crisis. For the same reason, votes favoured representatives of social movements, independents, and political party activists who explicitly proclaimed their opposition to neoliberalism. Yet, along with the make-up of the constitutional body, the deliberative process itself and the resulting constitutional text demonstrate that the Constitutional Convention was, in fact, a negation of the negation that the party of order had attempted to impose in November 2019, when it designed the limited constitutional process.

The popular class constitutional members gave voice to a broad set of grassroots initiatives that aimed to build the content of the new Constitution from the ground up. The territorial assemblies and social movements supported the constitutional process during an unprecedented moment of a new kind of mobilization — rather than taking to the streets in mass numbers, they engaged in a political debate about rights, democracy, institutions, and the guiding principles of social life.

It is true to say that we anticipated a mass mobilization on the streets, similar to that which occurred at the height of the October revolt. However, it is important to recall that all of this was made possible despite a right-wing government that routinely violated human rights and a pandemic that affected all areas of life and severely disrupted physical presence, a condition required for mass street mobilization. From this perspective, the grassroots mobilization and politicization that accompanied the constitutional process was consistent with the mass-movement and radical spirit of the revolt.

Principal Achievements

The new Constitution departs significantly from the frameworks provided by the 1980 Constitution in three key areas: principles, rights, and institutions. The new Constitution is distinguished primarily by a progressive approach in relation to gender, the environment, the recognition of indigenous peoples and the widening of democracy. This is clear throughout the text, from the definition of the State to the catalogue of rights.

For instance, the State is described in Article 1 as “social and democratic under the rule of law ... plurinational, intercultural, regional and ecological”, whose central purpose is to protect and guarantee individual and collective human rights. The cross-cutting nature of its principles is also manifested in its acknowledgement of structural inequalities in terms of gender and between the different nations that make up Chile’s population. This acknowledgement translates into an understanding that Chile is a “republic based on solidarity” with a democracy that is “inclusive and equal”, and that it must establish concrete mechanisms for the integration of its institutions on the basis of parity. Furthermore, it establishes a form of regional state that not only provides tools to decentralize national politics, but also aims to redress some of the historical injustices of a colonial State forcibly implanted in indigenous territories (Art. 187).

Finally, the new constitutional text has a clear environmental orientation, beginning with its acknowledgement of the ecological crisis and the need to address it in a decisive manner (Arts. 127 to 129). Such is the importance of this principle that it defines a sphere of natural common property that cannot be appropriated (Art. 134), which contrasts radically with the 1980 Constitution in which the opposite paradigm is crystalized: the integration of each and every sphere of life into the domain of private ownership.

Secondly, in recognition of the revolt that made it possible, the new Constitution includes a comprehensive set of rights, which is presented as a fundamental legal instrument for addressing the ongoing issue of precariousness that we will continue to experience in future years (Chapter II). In addition to amending the Constitution to incorporate international human rights standards, the document expands political, social, and cultural rights to levels previously unthinkable under the framework of the 1980 Constitution.

On the one hand, the subject of rights is no longer limited to the abstract concept of a person, but rather the actual reality of plurinational subjectivity: girls, boys and adolescents, men, women, and sexual dissidents, people with disabilities, people deprived of their liberty, old people, individuals and groups of the different nations, non-human animals, and nature in general. On the other hand, the rights that are guaranteed cover historical demands related to education, health, pensions, housing, sexuality, and work. These rights are universal in nature, and their articulation is accompanied by a clear trend towards the establishment of nationwide public systems supported by governmental funding to ensure their implementation.

One significant advancement is the provision for collective labour rights, which are grouped together under the concept of freedom of association and includes the right to form trade unions, engage in collective bargaining, and to strike (Art. 47). This way, the text breaks constitutionally with the dictatorship’s Labour Plan, creating the potential for a new framework of labour relations, and, most importantly, a new environment for trade union organization, which is now considerably diminished and constrained.

Similarly, the recognition of “domestic and care work [such as] jobs that are socially necessary and indispensable for the sustenance of life and the development of society” (Art. 49) implies a broadening of the concept of work and which for the first time includes a sector historically excluded both from collective rights as well as from the national accounts and the formulation of public policies. Accompanied by a Comprehensive Care System (Art. 50), this creates a huge potential for a significant part of the working class, girls, adolescents, and women to organize and contest the specific contents of this new category of rights. Notable is the inclusion of the right to a “voluntary termination of pregnancy” (Art. 61), which constitutionally enshrines a centuries-old feminist demand.

Furthermore, the changes to the Legislative Branch (currently composed of a Chamber of Deputies and a Senate) to establish an asymmetrical two-chamber system, with a Chamber of Deputies on a national level and a Chamber of Regions to allow territorial representation of the country’s regional entities, is notable at the institutional level (Chapter VII).

This change does not, of course, automatically usher in democracy for the lower classes, but when combined with the Popular Initiatives to propose or repeal laws, as well as the mandates to the state to guarantee an effective or binding participation at local, regional, and national levels, it is envisaged that there will be a revitalized period of political debate at all institutional levels. These developments are linked to a movement towards political self-representation among the organized grassroots sectors, which have been engaged in gaining a voice in the political struggle since the municipal and constitutional elections of 2021.

I would lastly like to briefly discuss the economic aspects of the new Constitution. In a significant departure from the current Constitution, the state is to participate more actively in the economy, as set forth in the new text in broader and more proactive terms. This is one of the areas in which the subsidiarity principle is abandoned, which states that the state may only intervene in areas in which the private sector is not already present, i.e., it is permitted a merely residual economic initiative.

The new Constitution recognizes the “initiative [of the state] to undertake economic activities, through the various forms of ownership, management, and organization authorized by law”, all in accordance with the “economic goals of solidarity, economic pluralism, productive diversification, and a social and solidarity-based economy” (Art. 182). This initiative also extends to the local government — represented by the autonomous communes — which is granted the power to set up companies in order to carry out its functions (Art. 214). With regard to the Central Bank, the criteria it must take into account in order to “contribute to the well-being of the population” are broadened to include financial, labour, and environmental aspects (Art. 358).

All of the above points to a restoration of the role of the state in the economy in a broader sense and based on democratic principles. Will it be possible in this context to move beyond the conventional establishment of public companies under capitalist corporate governance and transition towards democratic development planning at the local, regional, and national levels? Today more than ever, the economy needs to be liberated from the constraints and small-mindedness imposed on it by capitalism’s obsession with profit, and the lower classes need to gain greater control over the what, where, and how of production and its purpose in order to face the challenges presented by the global economic and ecological crises.

The Political Significance of the “Yes” Vote

Of course, all of the above is nothing more than what has been set out in the proposed new constitution. No more, but neither is it nothing less. This text is more than simply a collection of sentences — it is the culmination of a political debate that took place in the midst of the deepest crisis of our generation. It is therefore an instrument that establishes the foundations for the political struggles of the coming decades. The process is constituent because it gave rise to a new constitution and because a new political force is emerging within it that will work to implement and strengthen that constitution.

In other words, the new constitution will be introduced as the minimum programme of any transformative force in Chile if it is approved in the vote on 4 September. The Left will now find itself in an unprecedented situation where its focus will shift from the “dismantling” of neoliberalism to the implementation of a programme for democratization and social rights. Therefore, the plebiscite is presented as a strategic turning point in Chile’s long history of class struggle: it will mark the beginning of the working class’s counteroffensive, allowing it to finally escape the marginalization it was subjected to by the two-fold defeat of the 1973 coup and the neoliberal transition that began in 1988.

It will not be the triumph of its counteroffensive, nor even its main battle, but rather the beginning of the possibility of progressing beyond mere resistance and the modernization of its own precariousness to a stage in which the political struggle will be underpinned by a constitution partly created, defended, and approved by the people.

Without a doubt, this is not the ideal scenario, because we are currently experiencing one of the worst worldwide crises of capitalism, and we cannot completely rule out the possibility that this crisis will be resolved by a new authoritarianism under the leadership of the resurgent nationalist, conservative, and anti-popular right wing. But precisely because of this, a very real challenge is emerging: how will the social and political forces that took part in the constitutional process create a replacement that encourages the popular sectors to expand the structural reform process that was sparked by the revolt? This expansion will have to occur both through mass mobilization, which will provide programmatic support and a living force, and through institutional battles — electoral or otherwise — that will enable the construction of solid frontlines against the precarity of life and the advance of fascism on the streets and in the institutions, which are the main threats at the moment.

Unresolved Issues

From the perspective of the actual prospects that have been created for constitutional reform, it is remarkable that we have come this far. If approved, the text proposed will be one of the most progressive constitutions in the world.

Not only does it bring Chile up to par with international standards in terms of human rights, but it also establishes some elements that are unprecedented in comparative experience, such as the recognition of domestic and care work, which aims to advance towards its socialization, the right to a voluntary termination of pregnancy as a minimum in terms of sexual rights, and recognition of the existence of the environmental crisis and the challenges it poses. There is no doubt that we have seen a break with Chile’s neoliberal trajectory. However, it is a very Chilean-style break, within specific institutional frameworks, and without the participation of a powerful Left that looks beyond the progressive anti-neoliberal or social-democratic frame of reference.

Despite the considerable progress that has been accomplished, there are two unresolved challenges that may become part of the next phase of this same constitutional process. The first is to intensify de-privatization, something that requires, firstly, legislative implementation of the articles on non-privatizable common property such as water and, secondly, an expansion of public services and productive spheres over which the state should have priority in terms of ownership and management.

It is especially important in this case that mining revenues are no longer at the mercy of the private sector, because the possibility of financing social rights requires that these revenues be at the service of the public sector. This is not merely a legislative or constitutional struggle, but a battle for the heart of the national surplus.

The socialization of political power, particularly the extension of spheres of direct democracy to more fully include the people who have been shut out of politics, is another aspect that needs to be expanded and deepened. A reconfiguration of the criteria for participation in elected office yielded excellent results at the Constitutional Convention: gender parity, seats for indigenous peoples, and the opening up to independent lists should now be considered a democratic minimum as these will enable effective representation of the diversity of Chile’s peoples.

But state positions alone are not enough. Given Chile’s strong concentration of power in closed institutions, the country’s present political crisis demands an overhaul in how power is distributed. Over this protracted period of politicization, institutions must become permeable to the creativity of the masses, and public infrastructure must be made available to the community. By this I am not referring to more sophisticated consultations or limited advocacy. I’m talking about instances or bodies that provide for democratic resource planning at the local, regional, and national levels. The kind of democracy we need is one that eradicates the divide between the political and the economic, putting budgets and development plans in the hands of the people.

Finally, the removal of impunity for human rights violations during the dictatorship, the transition, and in the context of the revolt is an issue that remains to be resolved. These multiple layers of impunity only serve to embolden the most reactionary sectors, who are happy to see the armed forces given a free rein to abuse the people and to experiment with new tactics in times of crisis. The end of political imprisonment and of impunity in the armed forces has a strategic significance: impunity today is a guarantee that it will reoccur in the future.

The Rise of the “No” Camp

The centre and the Right, business associations, conservative groups, and the mass media (all of which are right-wing) have long been opposed to constitutional reform. The 1980 Constitution suits them just fine, and they have made this clear. They are afraid of democratic institutions that embrace a diverse group of people, and when they are receptive to reform, they think it should be in the hands of “experts” controlled or sponsored by the elite.

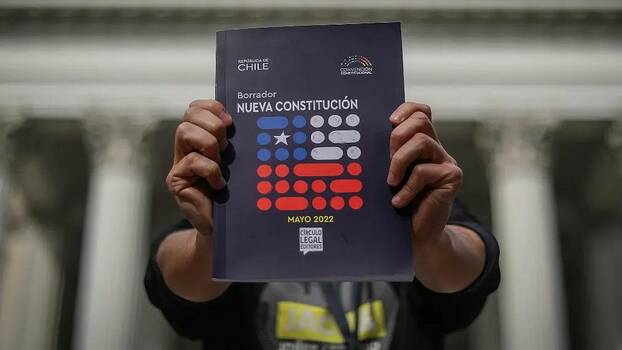

They had no choice but to accept this constitutional procedure, which they had opposed from the outset. They began campaigning against the new constitution even before the first article was written. Their campaign has been filled with hatred and lies, saying that the new constitution would bring nothing but chaos and poverty. They even oppose the distribution of the text of the new constitution — they oppose people reading it!

The fact is that they are ahead of us. They have been campaigning for more than a year against the constitutional process, and this has had an influence in the polls. In the midst of a high-impact economic crisis, they have built a strawman on which to pin all people’s fears. Their falsehoods have infiltrated deeply: there are people who truly believe that the new constitution may cause them to lose their houses and pensions, or that abortion will be legal up to nine months, or that indigenous peoples will have “privileges” over the rest of Chileans. Without delving into the specifics of the anti-feminist, racist, and anti-populist tropes they have deployed, these are concerns that have a clear foundation in the crisis, which indeed threaten some popular sectors with losing what little they have. But they also have a deeper historical basis.

The oligarchy in Chile is the only group that has brought chaos, poverty, and massacres to the country. It is the same group that carried out a double war of expansion at the end of the nineteenth century against Peru and Bolivia in the north and the Mapuche in the south. The same group that conspired with the CIA to boycott the Unidad Popular and organized a coup and a dictatorship of almost two decades. The same group that has fought tooth and nail to defend the precarity of the neoliberal status quo in Chile.

In a sense, the deep fears of the people of Chile are a response to the ruthlessness with which the elite has always defended its privileges. When they declare that chaos and poverty are coming, we all know deep in our intergenerational subconscious that it is the threat of the boss against the rebellious underclass. Of course, this is not entirely conscious reasoning, but it is undeniable that this deep historical dimension also comes into play in the current situation.

Gabriel Boric and the New Constitution

The 2019 revolt, the constitutional process, and the Boric government are clearly all part of the same picture within the wider process of change we are experiencing. The appraisal of each and their mutual relationship is most likely what characterizes the nuances among the many political viewpoints in Chile today.

Boric’s administration is in a difficult situation since a major component of his coalition’s programme, Apruebo Dignidad, rests on progressive (and radical) tax reform and a boost — such as that provided by the new constitution — to enable a process of a gradual guaranteeing of social rights. Without such dual backing its programme becomes diluted, and it will essentially be forced to make an adjustment (and thus continue repressing those who resist, as it has had to do thus far).

The first months of the government were very weak in terms of addressing the most urgent needs of the population, and the high approval rating with which it arrived at La Moneda quickly deflated. Only now, five months later, is it beginning to recover, owing to the implementation of concrete measures having a direct impact on the working class’s everyday social relations. But this weakness has meant that the identification between the government and the new constitution has been risky for both.

Boric needs the new constitution, and the constitutional process requires a government committed to circulating and executing the text once it is ratified. At the same time, the government recognizes that a victory for the “no” camp would be a long-term setback to its political initiative. And, for its part, it is not in the best interests of the constitutional process to be so inextricably linked to the government of a coalition that represented centrist — and at times conservative — positions in the constitutional debate and one that is vulnerable to attacks from both the Left and the Right.

In short, this is a highly complex situation that no unilateral position can resolve. Everything seems to indicate that the advancement of “yes” will stem from the activism of government coalition sectors, especially from the intensive deployment of social movements across the regions through their territorial networks and the political capital of those who served as their representatives in the Constitutional Convention.

The reactionary sectors have already launched their campaign of falsehoods and fear, and it appears that they have no other tactics at hand. Thus, once the proposed new constitution is known and the advancements it signifies are recognized, the “yes” vote is predicted to gain ground and prevail in the referendum. However, there is no room for complacency. The vote will not be determined until the very last moment, and every action taken by supporters and opponents will have a bearing on the outcome.

The Left and the Perpetual Problem of the Political Alternative

I would not want to conclude this assessment of Chile’s constitutional moment without mentioning the opportunities and challenges that are emerging for working-class political action, which now appears to be achieving the real possibility of unified action centred around a constitutional programme that is independent of the sectors that have administered the regime.

The constitutional process has revealed that we are currently in a process of overcoming the programme fragmentation that characterized the popular movement throughout the transitional period between 1990 and 2019. The new constitution is unquestionably positioned as the programme providing the most solid support for unity that the grassroots have seen since Unidad Popular. The breadth of demands it manages to include in the same political moment (which includes not just the constitutional text, but also the constitutional process) fosters a period of unity in working-class political action. This unification had not been possible under the anti-neoliberal politics of the Communist Party or the Broad Front (Frente Amplio), let alone under the fragmented and largely sectarian politics of the archipelago of militant organizations that have comprised our radical Left up to this point.

However, the experience of the unprecedented political struggle made possible by the revolt opens up fresh prospects. The revolt not only aimed to fulfil a range of sectoral demands, but it also rallied the people behind a deeper overall transformation. This experience was shared by millions of people across the country who participated in territorial assemblies, raised constitutional candidacies, and actively followed the constitutional debates.

The struggle for the release of political prisoners, the spaces of daily resistance in the face of the pandemic and the crisis, the participation in the political campaigns for the 2020 plebiscite, the second round of the presidential elections in 2021 and the coming referendum in 2022, and the ongoing exposure to a debate about the principles, rights, and institutions that should be included in the new constitution are all parts of a shared experience that go beyond the confines of the social struggles we saw in the previous phase. This experience, which is nothing more than a nascent engagement in the battle for power, is now facing the likelihood of a victory in the plebiscite, which would certainly usher in a new political cycle in Chile. The experience of a people who have awakened, had their hopes raised and fought and triumphed in a constitutional battle, will serve as the starting point of this cycle.

However, the likelihood of victory will be accompanied by the necessity to lead the change process and to guarantee that the terms underpinning the constitutional text are those of the people rather than those of the transitional parties eager to recapture the initiative. This is where the main difficulty arises at this present moment. In the same way that the revolt occurred when the grassroots were not an organized force capable of carrying out the terms of their uprising (resignation of Sebastián Piñera, Constituent Assembly without the tutelage it finally achieved, release of political prisoners, and the reversal of the repressive and detrimental policies of the state), we are now facing a potential victory for the “yes” camp in an organic situation that falls short of the demands of the moment.

The first thing we can foresee is that the new constitution’s implementation will be a process of fierce political conflict between groups representing differing levels of agreement with its content. The right-wingers — the far-right Republican Party and the Chile Vamos coalition — have openly come out against it and are the forces that are mobilizing behind “no”. The centre-left (for lack of a better name) represented by the Concertación and the liberal sectors of the Broad Front believes that the new constitution needs to be approved and reformed immediately.

The Left, represented by the majority of the Apruebo Dignidad coalition as well as social movements, indigenous peoples, and the archipelago of militant organizations, is the group expressing the most enthusiasm for the new constitution and the need to implement and strengthen it. However, because a section of the Left is in government, its independence in defending the new constitution will be compromised, as it will have to negotiate with the rest of the ruling coalitions to defend its position.

This opens the door for the formation of an independent political alternative to the government to take on the responsibility of defending, promoting, and finally leading the implementation of the new constitution, a process that will take decades. The problem is that this alternative does not yet exist.

Throughout this text I have advanced the idea that there are two unprecedented aspects in the recent history of the working class in Chile. The first is that the various sectoral demands have converged within a synthesizing programme, firstly in the feminist movement’s Programme Against the Precariousness of Life and subsequently in the design of the new Constitution. The second is that the experience of political struggle that led to the revolt and the constitutional process can be used to build an alternative that will not only implement a modern, progressive, and democratic constitution, but will also offer a transformative outlook from an anti-capitalist, feminist, eco-socialist, and plurinational standpoint.

However, these new developments in our recent history are accompanied by a reality that has endured for decades: the bloc that now represents the constitutional popular forces is still in a position of organizational and strategic vulnerability. This is a strategic weakness because debates about the development of the political capacity of the working class to bring about a revolutionary transformation of society have been reduced to Byzantine discussions of militant nuclei (which often seem more like history clubs than cadre organizations) or have been relegated to the margins by a popular movement driven by the urgency of the situation. This has resulted in a disconnection between the effort to achieve social gains and a long-term vision that links these gains to a wider-reaching transformation.

The constitutional process is a first glimpse of what it means to lay out a battle plan that includes not only a set of tactics and demands, but also a vision of the subjects, as well as the tools and paths to be taken in order to shift from a historical cycle of defeat to one of counteroffensive to ensure a transformational solution to the current crisis. However, the grassroots constitutional forces are also poorly organized. This means that these forces remain dispersed, each with reduced numbers, and lack the potential to achieve long-term improvements.

This challenge will not be resolved by identifying shared short-term goals, the best organizational design, or appealing to a desire to unite for the sake of unity. It is true that when the people are united they will never be defeated. But what defines a united people? I venture to close this text by offering a hypothesis for the present moment.

Today, the political experience of recent times presents the best opportunity for unity: from the revolt to the “yes” campaign, from the struggle for human rights to the community resistance during the pandemic, because this has been a common experience, shared by diverse sectors of the plurinational working class in Chile, in a short and intense period of time.

The formulation of a shared vocabulary and tactical repertoire around the revolt and the constitutional process make it possible to set up a forum for political debate among social movements, activist coordinators, collectives, and assemblies, militant organizations and other community efforts that recognize the need for a united front around the political cycle that begins on 5 September.

Alongside this, the new constitution is presented as a common foundational framework onto which the upcoming decades are projected, a kind of minimum programme for the cycle. The revolt and the constitutional process brought to the fore a diverse spectrum of political voices, embodied in feminist, ecological, indigenous, and trade union leaderships, people from all regions, with and without university degrees, and with and without political militancy. Some were elected as convention delegates, while others worked in teams for the Convention, whereas others remained in their territories campaigning for self-organization processes. These spokespersons are now well-recognized popular voices, and they must play a part in the process of unity.

This experience that the constituent grassroots have generated, side by side, this shared agenda using the new constitution as a springboard, and this voice of the people that reaches the masses, all point to the possibility today of starting to build a political front from the social movements that draws on the recent experience and sets out to organize the political process currently underway in order to face the forthcoming cycle.

There is a clear need for a common organized platform for us to address the upcoming debates in the most coordinated way possible, by democratically defining the political orientation of every aspect of our activism and struggle. There will be a need to learn the lessons of political alliances without programmatic agreements, as well as the tendency to abandon medium- and long-term strategic debates in favour of short-term tactical solutions (electoral, sectoral, and territorial), which are very real risks that have beset the Chilean Left in recent years.

However, it appears that we are now in the midst of an unprecedented window of opportunity to construct a political alternative in this present time that does not back down in the face of challenges and contradictions, and that continues to strengthen from below the revolutionary force of the feminist general strike, the popular revolt, and the constitutional process.