For me, Vietnam is an expression of the emergence of a new socialism of the twenty-first century — the formation of a new, third wave of socialism in Asia, Latin America, Europe, as well as Africa.

Michael Brie is chair of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation’s Academic Advisory Board. His recent publications include Rediscovering Lenin: Dialectics of Revolution & Metaphysics of Domination (Palgrave, 2019) and, together with Jörn Schütrumpf, Rosa Luxemburg: A Revolutionary Marxist at the Limits of Marxism (Palgrave, 2021).

This article is based on a presentation given at the conference “The Values of Socialism”, organized by the Institute of Philosophy at the Vietnam Academy of Social Sciences and the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation’s Hanoi Office on 2–3 November 2022.

What is special about the new approaches is that, unlike in the past, they are able to understand socialism as an organic system of contradictions. Precisely because socialism has always been understood as a society free of contradictions, the socialist movement — and with it the Communist movement — often became entangled in precisely those contradictions that a socialist movement must have, and ultimately fell victim to them.

One reason why the Left in Europe and the US is weak is that, at least for the moment, it is not able to deal properly with the class-based contradiction of neoliberal capitalism and lacks (not least) a proper concept of socialism. The Left is split between those tending towards a left social liberalism and a Left tending towards a kind of closed social nationalism. Until now, it has not able to combine these both currents into a new Left.

I view the socialism of the twenty-first century as a way of mediating between liberalism and communism on a new institutional basis and with new property and power relations, in a new political form, on a new basis of values. As such, socialism actually represents the path of survival that goes beyond liberalism and old forms of communism.

The communist foundations form the common “earth” of this society. Freedom, equality, and solidarity are its fixed stars in the “sky”. The actors and institutions of socialism mediate between this sky and this earth. Each and every one is thus given the chance to live a full, rich life.

The value system of this socialism relates equally to the values of emancipation of the individual and to the communal development of all in solidarity. Defining socialism thus means defining its central contradictions.

The Two Forms of Socialist Wealth

Karl Marx began his main work with the following sentence: “The wealth of those societies in which the capitalist mode of production prevails, presents itself as ‘an immense accumulation of commodities’, its unit being a single commodity.”

If it is the mass of commodities by which the wealth of a capitalist society is measured, in what way is the wealth of a “good society” beyond capitalism measured? How does it appear?

In the everyday understanding of the majority of citizens, according to many surveys, the wealth of a “good society” has not one but two points of reference — first, the possibilities of freedom and immediate life relationships of the individual, and second, the common goods that make a good life in solidarity possible.

If we were to place these notions into a sentence referring to a socialist mode of production analogous to the first sentence of Marxʼs Capital, it would sound something like: “The wealth of societies in which a socialist mode of production prevails appears, on the one hand, as the wealth of possibilities for the free development of individuals in interpersonal relationships, and, on the other hand, as the wealth of the natural, social, and cultural common goods that are available to all in common.”

The Two Formulas of Socialism

Marx developed a general formula of capital in Capital: “Value therefore now becomes value in process, money in process, and, as such, capital. It comes out of circulation, enters into it again, preserves and multiplies itself within its circuit, comes back out of it with expanded bulk, and begins the same round ever afresh. ... M—C—M' is therefore in reality the general formula of capital as it appears prima facie within the sphere of circulation.”

This general formula expresses the goal of every capitalist context of reproduction: capitalism is always about self-valorization, that is, the extended reproduction of the advanced capital. If this goal dominates the economy of a society, the capitalist mode of production rules in it. If this mode of production dominates the society, we can speak of “capitalism”.

One of the most difficult questions of shaping socialist relations is finding the political form for the expression of contradictions. The wills of the many and the wills of communities do not coincide and never point in the same direction.

If we try to express what has been said in a formula, it becomes clear that there must be not only one, but two general formulas of socialism if we want to grasp the interrelation of the two poles of wealth in a socialist society.

On the one hand, the goal of a socialist society is to reproduce the common goods of such a society (expressed as CG) in an expanded way, so that CG + ∆CG = CG'. Thus, a society would be called socialist if the reproduction and development of the commons takes place through the free development of the social individuality of the members of society (expressed as I). In the measure of the expanded reproduction of the common goods, an increase in the wealth of individuality takes place at the same time (I + ∆I = I'). Expressed in a formula, this would be: CG → I + ∆I → CG', or: CG → I' → CG'. That would constitute the first general formula of socialism.

Secondly, it is equally the aim of a socialist society to develop the social individuality of each of its members by having them contribute to the development of the commons. Thus, it would also hold that: I → CG + ∆CG → I', or: I → CG' → I'. This represents the second general formula of socialism.

The first general formula formulates the development of the communal as the goal and considers the development of individuals as the means of the development of the communal. This is the general communist formula of socialism. The libertarian formula of socialism, on the other hand, focuses on the development of individuals as the goal and considers the wealth of the commons as the means of the same.

The Complexity of Socialist Relations in the Reproduction Process

A socialist economy is a complex economy in which a very high number of relatively independent economic actors cooperate with each other in a division of labour, and at the same time constantly combine the available factors of production (natural resources, machinery, labour, knowledge) in new and different ways, using the material, social, cultural, and digital infrastructure at their disposal.

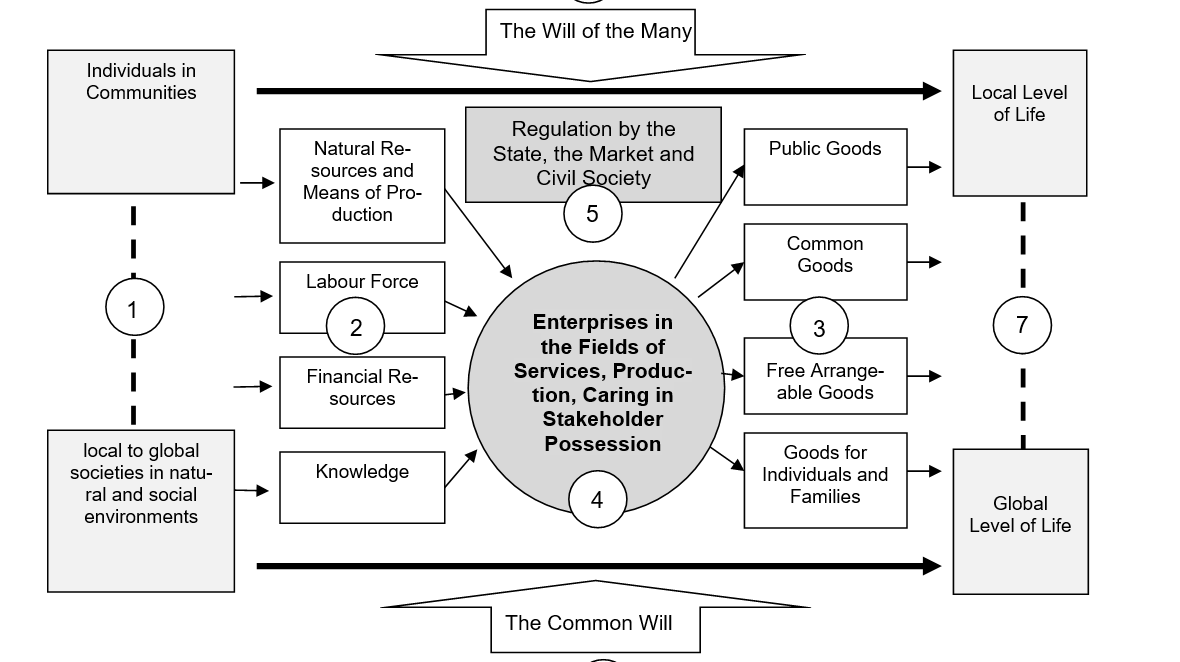

In the following, I will suggest how to approach the search for socialist forms of processing the complexity of modern societies. The problem posed by the two general formulas of socialism can be formulated thus: under what conditions can economic factors (labour power, natural resources and means of production, infrastructure, knowledge, culture) be combined in a complex society in such a way that enables a mutually beneficial development of the social individuality of society’s members and of society’s commons, improving above all the situation of the worst off? This also raises the question of how the political community must be structured in order to establish and maintain such socialist reproduction.

The Two Owners in Socialism: Individuals and Society

A socialist society has not one but two purposes. Neither the free development of the individuals nor the solidary development of all is at the centre of attention, but rather the solidary connection of both goals in one way. Logically, this means that it must be assumed that in socialism there is not one owner, but two owners related to each other and not reducible to each other.

On the one hand, these are the associative individuals as individuals who relate to the communal conditions of reproduction as their “organic body” through which they maintain and develop as free individuals. On the other hand, the associated individuals are also owners as members of society, who organize the reproduction of the social body with the aim of developing the natural and social commons of a rich life, and precisely through this, secure the conditions of the free development of their members.

The contradiction between the individuals as individual owners on the one hand and as social owners on the other hand must be resolved. This can only be done through a great plurality of forms of ownership, centred on socialist economic enterprises.

The Plurality of Socialist Forms of Ownership

It would be a fruitless endeavour to search for the one ideal form of ownership of a socialist society. Given the complexity of society and the variety of goods necessary for the realization of the dual goal of property ownership, property relations must be shaped in an open search process and with the possibility of constant evolution.

The table depicted above illustrates the space in which this search should take place. It also illustrates that the different forms of ownership are associated with different forms of economy — from gift economy, to common economy, to exchange economy, to self-sufficiency economy. However, this does not say which property order they serve. It can be capitalist or socialist or even purely statist. That depends above all on the overall context.

From the point of view of use, those actors should be owners of the goods mentioned who have the highest interest in exploiting their inherent potentials in the interest of the overarching owners — in the case of a socialist society, that is, the individuals and the society as a whole. Public goods should be open to free use by as many as possible, since their use increases the benefit for society without exploiting these goods. They should be owned by the public — i.e., no one.

Common goods should be owned by those who, on the one hand, ensure that no one is excluded from access who has a right to them and, on the other hand, ensure that there is no overuse and that the constant renewal of the good is guaranteed. They should therefore be owned by clearly defined communities. While individual and small-group goods should also remain in the possession of individuals and small groups (partnerships, families, etc.), there is a need for clear regulation of the conditions under which associated goods can be owned and how they can be disposed of.

In socialism, the democratic sovereign always exists twice — as the sovereignty of the will of the many in the individual interest, and as the sovereignty of the will of all in the common interest.

Associated ownership must be able to combine the interests of all those who have a stake in its use. One could also speak of stakeholder ownership. In stakeholder ownership, the rights of access, withdrawal, management, exclusion, and disposal are distributed among the actors involved and affected in such a way that the interests of these actors are taken into account as comprehensively as possible, while preserving the company’s or organization’s ability to develop. It is a question of balancing solidarity and freedom.

There are four essential criteria for the concrete design of the forms of ownership.

First, the central function of the service to be provided must be determined. If, for example, infrastructure and services are to be provided for society as a whole (or for an entire region or municipality), then the public interest dominates. In companies that provide these services, the representatives of the overall public interests must have the dominant position in the orientation of the companies.

In the case of platforms, it is primarily the users who deserve this dominant position. In the case of many consumer goods, it is the consumers. They can express their interests primarily through solvent demand, consumer organizations, and local sales networks.

Secondly, other interests must be defined that are important in the production and use of goods and services, and it must be asked how they are represented. This can be done through government-imposed standards, prohibitions, environmental organizations, local and regional governments, non-profit organizations, and so on. In some cases, it is a matter of influencing entire global supply chains or processes from manufacturing to recycling of raw materials.

Third, it is about representing the interests of the workforce. This includes good work, good wages, and participation in shaping working conditions, product development, and corporate strategy.

Fourth, it is about defining the rights and duties of management in such a way that, under the conditions of this diversity of stakeholders and in their service, entrepreneurial tasks can be fulfilled with the necessary decisiveness. Their task is to translate the interests of the stakeholders into development of the company.

The Will of the Many and the Common Will

One of the most difficult questions of shaping socialist relations is finding the political form for the expression of the aforementioned contradictions. The wills of the many and the wills of communities do not coincide and never point in the same direction.

In socialism, the democratic sovereign always exists twice — as the sovereignty of the will of the many in the individual interest, and as the sovereignty of the will of all in the common interest. The contradiction between the will of the many as individuals or as individual groups on the one hand, and the will of the community on the other, reflects the contradiction of complex societies between the reproduction and development of the individuals and the reproduction and development of the body of society.

A socialist society that has overcome the dominance of capital over the economy and society must politically work out this multiplicity of contradictions. Just as its goal is twofold, expressed in the two general formulas of socialism, just as its property order is organized around two poles (individuals and the society as a whole), so too its political order must incorporate two opposing traditions — that of liberal democracy with the primacy of the interests of individuals, and that of popular democracy.

Vietnam’s development is a model for socialism in the twenty-first century. It is a living, deeply contradictory, experimenting, and learning socialism under the leadership of the Communist Party of Vietnam. The Rosa Luxemburg Foundation is very grateful to be in fruitful dialogue with our colleagues and friends in that country.