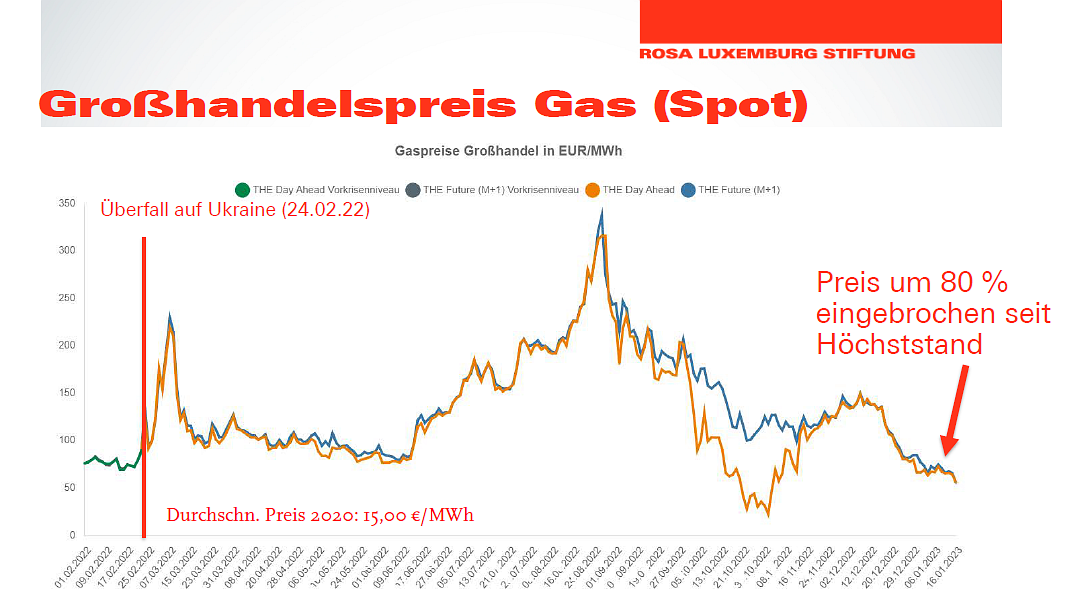

After the breath-taking spike in energy costs Germany saw last year, at least wholesale prices for electricity and gas have fallen back to pre-war levels — “at least” in the sense that it will take a while before these price reductions actually reach end consumers.

Uwe Witt works on climate protection and structural change at the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation’s Institute for Critical Social Analysis in Berlin.

Translated by Loren Balhorn.

There is also another caveat: returning to the price levels we saw prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 does not yet mean a return to the price level that prevailed in spring 2021, for example. After all, the price hikes on the energy market in fact began months before the war.

The Gas Price Wave

The rapid rise in energy prices was caused by several simultaneous factors. A long, cold winter in 2020–21 emptied German gas storage facilities. In addition, a surprisingly high global demand for gas in Asia after the pandemic lockdowns were lifted had just as much of an impact on prices as the conflict with Russia over EU approval of connecting the Nord Stream 2 Baltic Sea pipeline to the European gas network.

Although the Russian state-owned company Gazprom initially continued to fulfil its long-term supply contracts with Germany, it barely offered any gas on the shorter-term forward and short-term spot market at European trading hubs. Usually, importers and gas suppliers only cover part of their long-term contracts, as it only becomes clear how the winter and corresponding demand for gas will develop closer to the time of fulfilment.

As a result, prices on the gas market, which is sensitive to shortages, shot up to unimaginable heights, from around 1.5 to 2 cents per kilowatt hour (ct/kWh) as originally quoted before the summer of 2021 to 14 ct/kWh around the turn of 2021–22, only to fall again by the start of the war in February, albeit still to a level of 6 to 8 ct/kWh. This now roughly represents the current wholesale gas price level — not only on the spot market, but also for supply contracts with fulfilment periods for the next few months, and even for the winter of 2023–24.

That said, this lower price level will only reach the end customer in a few months (wholesale prices only make up part of end customer prices anyway), because, as is well known, the most drastic price explosion occurred between the beginning of the war and today. Because Russia increasingly tightened its supplies to Europe and ultimately stopped them completely (the EU never imposed a natural gas embargo), gas prices on the European TTF spot market climbed to an astronomical 32 ct/kWh by late August 2022, before falling again.

Of course, this monster wave of additional procurement costs did not only flow into short-term contracts. It also proportionately influenced supply agreements with a horizon until the winter of 2023–24. Only the restructuring of supply relationships and successful gas savings (also due to the mild winter) brought the wave to an end.

The Electricity Price Wave

A similar two-stage wave crest could be observed for electricity prices. Because the electricity market is decisively influenced by gas prices, spot market prices have also gone through the roof since summer 2021: from a level around 5 ct/kWh in spring 2021 to over 30 ct/kWh at the beginning of October 2021, and even 42 ct/kWh shortly before Christmas. This was followed by a recovery to 13 ct/kWh before the start of the war. Then came the big price spike of up to 70 cents last summer.

Today’s prices, on the other hand, fluctuate between 0 and 15 ct/kWh on the volatile spot market and 14 to 21 ct/kWh on the futures market with fulfilment in the first to fourth quarter of 2024. As with gas, they are on average three times what gas cost on the wholesale market in spring 2021. The rise in CO2 prices in the European Emissions Trading Scheme, which were still at 25 euro per tonne at the beginning of 2021 and now fluctuate around 80 euro, also plays a smaller role in this development.

The volume of these historic waves (to stick with the metaphor) unfortunately will not evaporate so easily. It is distributed in the gas and electricity bills of households or industry or in the mountains of debt found in public budgets and the special funds that finance the German state’s energy price brakes. It filled and continues to fill the bank accounts of gas companies, liquefied gas traders, and electricity suppliers around the world, who continue to rake in massive profits — partly because the windfall profit tax levies are largely failing.

Ultimately, energy prices did not swell (or just barely did so) as a result of higher production costs. They climbed because gas is scarce.

The New Normal?

This means there will be no short-term price cuts. On the contrary, some providers could still expect slightly higher end-customer prices for the time being, especially default providers. That is because the long-term contracts that were cheap at the time of signing are increasingly disappearing from their portfolios, while the expensive ones from last year are likely to gain in importance. It will be some time before these in turn are displaced by current developments (which will first arrive with new contracts).

Moreover, there are still some unknowns to be taken into account: whether the next winter will be as mild as the current one has been so far and, consequently, whether there could be new price surges on the wholesale market is anybody’s guess. Yet even if they do not occur, the liquefied gas now being ordered is more expensive than pipeline gas due to compression and the need to transport by ship. Thus, current prices will probably become the “new normal”.

A problem that has dogged German energy markets for years is gaining relevance: namely, to what extent and when do providers pass on falling prices to end customers? For, in contrast to the wholesale market, the end-customer market is hardly supervised.

Until now, the German government sought to regulate the energy market with the magic formula of simply “switching providers”. Various studies on the subject have shown that this approach hardly worked in the past. In addition to the traditional inertia of many private households to switch, which involuntarily fuels unfair business practices, consumers currently must fear the spectre of reckless operators on the energy market who lure new customers with cheap offers but then go bankrupt, as happened to several providers last year. No wonder the Süddeutsche Zeitung already noted last November that “the number of complaints at the nationwide energy arbitration board is higher than ever”. The stricter monitoring of suppliers that the government introduced last year in connection with the energy discounter scandals seems to be blind to the unscrupulous pricing of some suppliers.

What does this all mean for German consumers? Prices on the wholesale energy markets have recovered, but they will not return to the old level in the foreseeable future. In any case, it will take a while before the falling prices reach the end consumer, and in the meantime, the government’s energy price brakes will soften some, but not all, of the impact. Both windfall profit taxes and price supervision for the end consumer sector must be reformed. The role of the state must be given more weight here and cannot, as some associations of energy companies have demanded, be rolled back.