Cuban emigration to the United States and Europe during the post-pandemic crisis has reached unprecedented heights. According to United States Customs and Border Protection, 225,000 Cuban emigrants left the island in 2022. It has grown so significant and developed so quickly that university journalism courses in Cuba have started integrating demography and migration into their course plan.

Federico Mastrogiovanni is an Italian journalist who has lived in Mexico since 2009. He was honoured with the Mexican PEN Association award for his book Ni vivos ni muertos (Penguin Random House, 2016).

Translation by Michael Dorrity and Joseph Keady for Gegensatz Translation Collective.

As of January 2023, the US government established what are known as “parole processes” to normalize immigration. This allows for a maximum monthly arrival of 30,000 Cubans, Venezuelans, Nicaraguans, and Haitians who have obtained advance authorization (the “parole”) online and are supported by a relative or acquaintance who is already a resident of the US and can serves as their financial guarantor.

These measures also ensure that anyone who arrives at the US border without authorization will be immediately deported and denied entry into the country for the next five years. The parole process was designed to discourage migration via Mexico and to regulate arrivals in the United States.

Until now, the underlying assumption in many discussions about emigration in Cuba has been the option of “taking the volcanoes route”, i.e. travelling via Nicaragua, where Cubans are not required to have a visa. From Nicaragua, the journey to the US takes them through Honduras, Guatemala, and Mexico.

In November 2022, Zoraida, a homeowner who had been renting to tourists for almost 30 years, decided to leave Santiago de Cuba for Miami with her youngest son, her daughter-in-law, and her granddaughter.

I’m leaving on Friday morning at 6:00. First, I go to Santo Domingo, and from Santo Domingo to Kingston, Jamaica. From Kingston to Nicaragua and then… because they’re waiting for me there, in Managua. For me and my son, Toño. I’m going with him, my daughter-in-law, Simon’s wife, the eldest, and their daughter.

I’m doing it for them, and for me, because I need to go. So do they. I mean, they need you to be there for them. Yes, son, trust me, nothing’s going to happen to your daughter. I made up my mind a few days ago.

My nephews left in March. They all left. It was a shock to my son, the youngest. There were so many people in this house, so much joy, so much youth. It really came as a shock to my son Toño.

I had no other choice. My other son, Simon, was born in the wrong place. He’s been saying his home is in the States since the day he was born. Ever since he could speak, he’s been saying he was American, he dresses like one and everything. All of it, the whole thing. He speaks English, he’s intelligent, he does IT, which is what he studied. He’s a technician, because he didn’t want to finish college.

The baby, Toño, became a full-body masseur. He quit university after two years of studying physical education. That was that. And now there’s no other option.

As for me… I spent my whole youth here. Every little bit of it. I’ve been working in this house ever since Simon was born. I mean, I’m 56 and I’ve got no future. I’m tired. I’ve got a good life, a nice house, a family, but without my sons… one’s left already and the other one is getting ready to leave. What choice do I have?

I really don’t know. What am I supposed to do? When I imagine it, I think about being reborn, like taking on something completely different, some other life. But then my son says to me “Mom, don’t worry about it. Come as you are and you’ll see, it’ll be fine.”

The thing is, I’m a go-getter. I’m not afraid of anything, or any work. If I have to look after somebody in a hospital, I’ll do it. I’ll look after you, I’ll comfort you, all of it, not a problem. And I’ll look after you because it comes naturally to me. I want you to be OK. That’s who I am. And if I have to clean houses, I’ll clean houses, happily. That’s just who I am. And if I have to look after someone who’s unwell, I’ll do it, happily.

Zoraida has been renting out rooms in her house in Santiago de Cuba for 25 years. She complies with state regulations and hosts visitors from many countries. She was not among the hardest hit by the economic crisis or the shortages, given that she has always had access to foreign currency — dollars and euro. That is why she will be able to spend almost 30,000 euro to get to Miami with her son, daughter-in-law, and granddaughter via Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala, and Mexico.

I don’t care that there’s no food in Cuba. Yes, there’s no food, there’s a lot of things we don’t have, but I’ll eat whatever. I’m not worried about food. But I don’t like the sadness. I just don’t like it. I walk down the street looking at people’s faces, looking for the spark in their eyes, and it’s not there. There’s no hope in them. So, I don’t spend much time on the street. I stay here at home.

I prefer it when people bring me what I need instead of waiting in lines myself, because if I get into an argument with someone, if I end up in a fight, they’ll put me in prison. That’s the thing: I’ll fight. I’ll defend myself. I can’t stand injustice. So to stay out of trouble, I don’t go out. My boys told me I wasn’t allowed to anymore: “Mom, don’t go out anymore.” Because I get into fights, I know I do.

So when I get to Miami, I’ll be reborn. The business here, my house, everything stays. I already gave my sisters the rights to take over the business. Because I’ve got the clients. I’ve talked it all over with them already, I’ll leave them in charge, it’s all taken care of, all of it. There’s nothing left here. What am I going to offer clients here? I can’t even give them bread, not so much as a sandwich. I can’t offer them a thing, because there’s nothing to offer, not a thing. We just don’t have it.

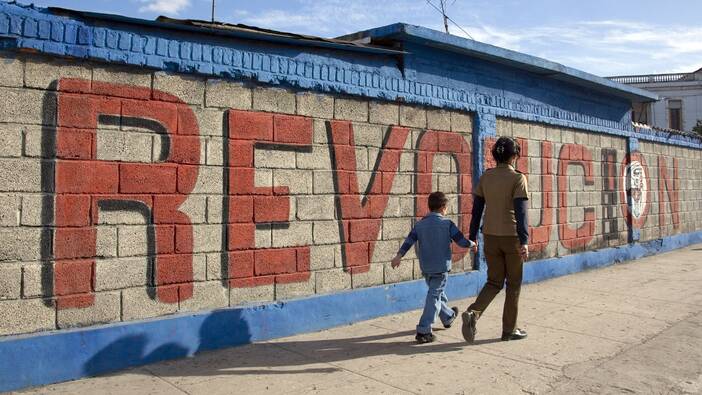

My son Simon left in March. He’s been there for eight months. I went to Suriname in 2017. I travelled, I got out of here. I woke up all the more after that. And I was born in a completely revolutionary family. My father was a colonel, got his pension from the Ministry of the Interior, 84 years old. He worked for this government more than 60 years. My father fought with the rebels. My mother, too. She was a campesina from the Sierra Maestra, and she helped the rebels. I mean, I’m not from a family where everyone’s over there now. No one from this family used to live abroad.

I had a cousin who won the [US visa] lottery in ‘98 and took her whole family over there, but that was it. But this exodus of migrants now… Simon used to say to me “Mom, I’m going”, and I’d say, “What? How? How are you going to get there?” Next thing he comes to me with a ticket in his hand, and I say, “Simon, oh Simon…”. So, I started selling things. I sold and I sold and I sold. I sold the bed, I sold whatever I could sell to pay his way.

My Simon’s 34 years old. For the longest time, he worked as a technician in a children’s hospital here in the neighbourhood. He said to me, “Look, mom, look at your certificate over there, look at it. I can’t earn what I want to earn here. Take a good look at it. It’s yours.” And off he went. He got a lot of work. He worked on construction sites for artists who pay their employees millions. That’s how he made his money. He doesn’t have a cent left because the ticket to Nicaragua cost 3,800 dollars. He went via Mexico: Havana, Nicaragua, Mexico.

He left on 2 March. It was awful. I weighed 81 kilos before that and I went down to 75 from suffering here in this armchair. I lit candles from the break of dawn, candles upon candles, praying, pleading, praying to every Virgin under the sun, praying to God. Me and my son, I was there with him in that little bus, three days. From Tapachula to Mexicali, three days in the bus and me there with him, morning, noon, and night. “Come on son, try to sleep a little. I’m cold… wrap up warm, son. I’ve got cramps from sitting still all day… stand up. Mom, it’s so dark in here… get up and move your foot, don’t let it fall asleep on you, don’t take your shoe off because you won’t get in back on again.”

When he arrived in the States, his feet were rotten, absolutely rotten. But he got there. Now he’s living with a Cuban friend of mine, and she has some money. He’s working in a steel mill for boats with my friend’s husband. Because my friend’s an American citizen now. Her husband, too. They have a nice house with a pool, and she looks after him like he was her own son.

My friend has two American kids. She’s been living in the United States for more than 30 years. She left when she was very young, and she has two kids. Simon is like a son to her because her own kids don’t live with her and she works at the University of Orlando. When I get there, I’m going to live with her until we have enough to look after ourselves.

Most Latin American immigrants do not have the same conditions as Cubans do when they arrive. Immigration for Cubans is somewhat privileged because it is easier for them to get a residency permit. Likewise, the journey to the US is less traumatic than for the majority of Central Americans. From Santiago de Cuba, Zoraida will take a flight to Kingston, Jamaica. From there, the plan is to fly to Managua, where she will be picked up by coyotes. She will go through Honduras, Guatemala, and Belize before finally driving to Cancun.

From Cancun, we’ll take a direct flight to Mexicali, where we’ll hand ourselves over. It’s seven days to get there. Seven days. We should get there 16 December. Seven days, with a coyote, a guide… one we know already. He’s Cuban, but he lives in the States. He won’t be picking us up personally, but he’ll send his people. He manages people in Nicaragua, in Honduras. A lot of people have made the trip with him.

The journey’s unbelievable. 7,500 dollars each — per person. Even for my granddaughter, the little one, 7,500 dollars per person. There’s four of us: me, my son Toño, my daughter-in-law, and the little girl. My daughter-in-law is Simon's wife and they have a daughter together. It’s a lot of money, but when I talked to Simon, he said, “Mom, it’s OK.” My son’s been working. He put up half the money. The other half is another story. We’re all going to work. At least I’m going to work. I’ve always been very independent, and I like to have my own money.

I still support my sons. I help them. My grandmother has a saying: a mother may have ten children, but ten children don’t have one mother.

So there you have it. I’ve made my decision, and I’m going. Yesterday I broke the news to my brother, then I told my mother and my father.

When I can, I’ll come back, like a lot of people do. I’ll get my residency, and I’ll come back and travel the world with my sons. Once you’ve got a residency permit, you can go to Canada, you can go wherever you want, and that’s my goal. I’m 56 years old. I can see myself in my mother, in my parents, like a mirror, and I don’t want that life. I travelled to Suriname before. I’ve got a visa for Panama for the next five years. I’ve never been to Panama.

The pandemic opened people’s eyes — the entire world, not just Cuba. The other day my sister says to me, “Ay señorita, let’s go to the Mesón”, and I say “Great! Let’s go!” I danced the night away, had a wonderful time, laughed, and came home happy. You know what I mean? May God give me health, may the heavens open and the earth be raised, let there be beauty and happiness. That’s what I want. I don’t like sadness, I don’t like depression, I don’t like poverty. It’s depressing… it’s depressing!

My mother’s 81 years old, she’ll soon be 82. She’s very lucid, and we keep her active. Goodness, my mother, she drives us crazy. She’s an elderly woman, and there’s a million different things she wants to do, but she can’t. “My back’s killing me”, she’ll say, “Don’t do that!” But we leave her be. She cooks, she hangs out the washing, because she has to keep her mind active. She reads the paper, she sews, the whole thing. You have to let her do things, do all the things she wants to. She doesn’t want to be left with nothing to do.

She made me sad yesterday. I consoled her and kissed her, I kissed her so much. “It’ll be OK, mom.” And my dad, he teared up when I told them I was going. He says to me “Puti”, he says, “Goddammit, Puti”, and I say to him, “But dad, the boys are there. They need me, I have to go tend to the flock. They’re lost, I have to go get them in line, this, that, the other, see how they’re doing.” Next thing I knew, he was streaming tears.

I have to go. We’ll see. We’ll focus on how things are. Besides, if they all work together and make money, money, money, they might even be able to — I mean, maybe not buy, no, but rent a house and all live together. They always lived all together. Toño’s over the moon. He’s going to live with his cousins, with his brother.

When my son Simon was on his way there, I prayed so much. I’d get down on my knees and say “Lord, let him arrive OK. Our Lady of Guadalupe, let him get through your land OK.” All that stuff a mother prays for. And when he was about to cross, my son said to me, “Mom, I feel like somebody’s pulling me along”.

He crossed the river because he got in through California, up by San Diego or Tijuana or Mexicali. He came out the other side and he said to me, “Mom, it’s over, I made it. It’s done, mom, I got through.” God in Heaven, that was it! I burst into tears. I was overjoyed. I was so happy, I can’t tell you. All on his own, he went all on his own, and he was so lucky that nobody abducted him, that nothing happened to him.

But I don’t want to stay here. I just don’t want to. My friends who met him in Miami celebrated his birthday with him. My happy son. I want to see him. And he says to me, “Mom, don’t worry, everything will be OK, mom, you’ll see”. I’m sick with worry, but so what? I’ll live. He called me four times this morning. He’s been calling me a lot, because on the ninth, at 6:00 in the morning, I’m off. My flight is at 10:45. We have to be there at eight. Simon told me he’s going to take me on a boat tour once I’m there. Here’s a photo.

Zoraida took a flight to Nicaragua on 9 December 2022. Rather than taking one week, it took her almost three. She arrived in Miami with her son Toño, her daughter-in-law, and her granddaughter at the beginning of 2023. She writes:

The trip was OK. It was worse once we got here. They separated us, and we had no news from each another. That really affected me.

We got to the States on the twentieth. I was the last one to get out. My daughter-in-law and granddaughter were the first ones to be released from the detention centre. They went to Chicago, and from there they travelled to Miami. They were only in the detention centre for 48 hours. They got out on the twenty-third. They let Toño out on the twenty-fourth, but he had to sleep in the airport for one night, because there were no flights to Miami. We were reunited in Miami on the twenty-fifth. They let me go in the middle of some park in Calexico. It was really something, but when I saw my family, I have no words for how I felt.

But things are almost normal now. Little by little, the migraines are starting to go, along with the pressure, which is why they started. Anyway, the nightmare’s over, and I’m with my family. We’re working on getting our papers, and I’m hoping to start working soon, start getting ahead like my sons are. But it all takes time.

Hopefully I’ll adapt quickly, although I was already a capitalist. I want to move forward little by little. We already applied for the papers to get my granddaughter into school at least. She was so brave during the whole journey. She was such a champ. She kept me going. We always travelled at night and rested during the day. Honestly, we’re so proud of her. She didn’t fuss or whine once. She’s doing her fair share now though (laughs). What more can I say?