In May 2024, Panamanians will go to the polls with a lot on their minds: the pension system’s long expected bankruptcy is expected to happen in October 2023, meaning thousands of workers who are eligible for pensions may not get any money. More than half of the population, who work informally, are not even eligible. Despite government promises, food and medicine prices continue to increase, the Panamanian basic food basket already being the third-most expensive in the region. All in all, poverty rates are rising, and Panamanians are angry.

Octavio García Soto is a Panamanian-Chilean freelance journalist with a focus on Latin America.

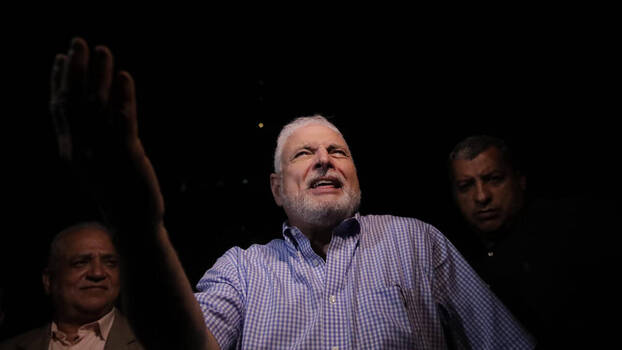

Ten candidates are running for president, and their outlook varies greatly depending on the polls. What they do have in common: Former president Ricardo Martinelli, a right-wing supermarket magnate, is the favourite, receiving the support of over 40 percent of eligible voters. Martinelli is awaiting arrest after being found guilty of laundering state money, which would force him to step down from the race… if the justice system acts. Despite his corruption and authoritarianism, the controversial Martinelli has retained the outsider clout that won him his first term, and he enjoys wide support from across the political spectrum. If he steps aside, it is anyone’s guess which candidates will stand to benefit.

Many independent candidates have also come to challenge the current political hegemony, among them the only leftist in the race. Their popularity is as of yet unknown, as their candidacies have only recently been officially registered. Aside from Martinelli, there is little numerical difference between the candidates, and with general anger towards established parties at an all-time high, expectations are high for the independents. The outcome of this election is the most uncertain in decades.

The Proto-Trump Right

Martinelli can still appeal to the court, but many are sceptical on whether the justice system will take any action against him after this period. Just like the political class, the judiciary has historically been under fire for its corruption. Many political parties are waiting for the outcome of the election before deciding on whether to form alliances with Martinelli. If imprisoned, his wife, the far less popular Marta de Martinelli, is expected to take his place.

Martinelli’s government was heavy on police violence and espionage against opponents and leftists.

Martinelli is running with his newly-founded RM party (Realizando Metas, or Accomplishing Goals), having left his first personalized project, CD (Democratic Change), after other figures rose to challenge his influence. During Martinelli’s presidency, CD rose to be the political party with the second-highest membership in the country, even prompting deputies to change parties in the middle of their terms.

Martinelli is facing ten years in prison for laundering state money to buy EPASA, a newspaper conglomerate that was favourable to him during his administration, and which remains so to this day. This is one of the many blatant examples of authoritarian overreach by the eccentric and corrupt magnate president, a Trump before Trump.

Martinelli’s government was heavy on police violence and espionage against opponents and leftists. He has been twice indicted for surveillance, but was absolved for lack of evidence of direct involvement. His 2010 repression of striking plantation workers in the Changuinola district remains infamous to this day. The Indigenous workers had taken to the streets, protesting a government bill that attacked the right to strike and union’s funds. This government repression resulted in 400 people being wounded, among them many who were permanently blinded. While the official tally points to at least two dead workers, others point to a higher number, including five children who died from the effects of tear gas.

But Martinelli’s initial measures also gained him long-lasting support: a 100-dollar subsidy for retirees, issuing laptops for public school students, and major infrastructure works such as the Panama City subway.

CD is now running against Martinelli through their current president Romulo Roux, who came second in the last elections, but currently stands fourth in many polls. It is expected for Roux to make an alliance with the conservative Panameñista Party and their candidate, José Isabel Blandón, who has similar poll numbers, as well as the small ultraconservative PAIS party, which has a candidate of its own, José Álvarez. But despite the number of parties involved, there seems to be little prospect of a win for Panama’s “traditional right”, given Roux’s and Blandón’s low popularity and PAIS’s lack of appeal when faced with Martinelli’s charisma.

The Party in Government

The current government is headed by Laurentino Cortizo, from the social democratic PRD (Revolutionary Democratic Party), Panama’s biggest party. Its candidate for 2024, Vice President José Gabriel Carrizo, is highly unpopular, and his primary campaign has been accused of using state funds, as well as of intimidating party members.

The PRD was founded in 1979 by dictator Omar Torrijos, who was popular for his social policies and for negotiating the treaty that gave Panama sovereignty over the Canal. Despite its founder’s leanings towards social policies, the PRD has always been close to the economic elites, and since the 90s has made major contributions to the dismantling of Panama’s welfare state.

Martín Torrijos, the dictator’s son, was president from 2004 to 2009. In March, he released a video condemning the corruption in the PRD leadership and announced his own bid outside of the party. His initial press has been positive, lauding his campaign tours, where he listened to the grievances of different social and cultural sectors, like the Afro-Panamanian community, musicians, students, and Indigenous peoples.

Only seven percent of overall public campaign money is given to independent candidates. Despite this obstacle, they have gained widespread popularity.

Despite being supported by the Christian democratic PP (Popular Party), which is a much smaller party than the PRD, some polls put him second. Aided by his government’s comparatively low corruption in comparison with the administrations that came after, Torrijos is also depicting himself as an outsider and his campaign is fostering this image by joining forces with independents.

Martín Torrijos’s government contributed to poverty reduction and economic growth, and held the referendum to expand the Canal. But he was nevertheless a neoliberal, whose social security reforms undermined the solidarity-based pensions system, putting it on its path to bankruptcy.

The Independents, Old and New

Only seven percent of overall public campaign money is given to independent candidates. Despite this obstacle, they have gained widespread popularity. The 2019 general elections were their highest point yet, as centre-right presidential candidate Ricardo Lombana won third place and six independents were elected to Congress. All of them campaigned on a heavy anti-corruption agenda, echoing the popular middle-class discourse of the state as an inherently incapable administrator.

Lombana is running again for 2024, and occupies third place in many polls. While he continues to support other independent candidates, he now runs a party of his own, MOCA (Another Way Movement). Lombana has espoused progressive causes like gay marriage and opposition to open-air mining, but warns independent candidates in his alliance against taking a stance, otherwise “the corrupt would win”.

While he has promised new public hospitals and protection programmes for women, the majority of his proposals aim to defund the state’s networks of corruption without strengthening it for the better, opting rather for solutions based on the free market. He promises to limit the president’s spending power and deputies' payrolls, to lower subsidies to constituted political parties, reduce the amount of scholarships awarded due to “economic necessity”, in reality often given out because of nepotism, and to create an apprenticeship system alongside companies.

On the pressing social security issue, Maribel Gordón is the only candidate who won’t consider raising the retirement age, even as a worst case scenario.

Three independent candidates will be running for president: Zulay Rodriguez, Maribel Gordón, and Melitón Arrocha. They were among the hundreds who submitted their candidacies during the anti-government protests of July 2022. Due to a loophole in electoral legislation, many of them were politicians from traditional parties, among them Rodriguez and Arrocha. Rodriguez, PRD, is a nationalist who grew popular through her xenophobic rhetoric and whose public image has recently taken a hit through leaked telephone conversations that link her to the drug trade. Arrocha was Commerce Minister during Juan Carlos Varela’s administration (2014–19).

The Left

The remaining independent is the economist and teacher Maribel Gordón, who is also the only leftist in the race. In the midst of the 2022 protests, she negotiated with the government on behalf of social movements and trade unions, which demanded price cuts on food and fuel. These same organizations are pushing her candidacy now.

Gordón proposes a national economic plan, the “Plan for the Dignified Life”, which would empower national food production in the agricultural sector and revive Panamanian industry, dismantled during neoliberalization. On the pressing social security issue, she is the only candidate who won’t consider raising the retirement age, even as a worst case scenario.

In May 2024, Panamanians will have to choose between a return to authoritarianism, a crumbling status quo, and a new economic model.

This is Gordón’s second time in the race. In 2019, she ran for vice president alongside trade unionist Saúl Méndez, for the leftist FAD party (Broad Front for Democracy), which disappeared after their meagre result of 0.6 percent, or 13,540 votes. Now, as an independent, Gordón has collected over 160,000 signatures to make her candidacy official. This is the most attention any leftist presidential campaign has received in over 30 years of democracy.

Three Alternatives for Panamanians

Another countrywide explosion similar to the one that happened in July 2022 is not a matter of if, but when. And with nine out of the ten candidates being free market apologists, the chances are low for a sustainable solution to the prices of medicine, food and fuel, the social security crisis, and the precarious labour situation of most Panamanians.

Furthermore, a second Martinelli administration would exacerbate the current economic crisis and bring a wave of political persecution as it clashes with a population less afraid of social protest. Martinelli would likely join El Salvador’s Nayib Bukele in the ranks of entrepreneurial strongmen in Central America. Conversely, were Maribel Gordón to be elected, the road to economic reform would not be easy. There is no leftist party to push for mass candidacies to Congress. Gordón would also be facing the petrified political caste and an oligarchy with a monopoly on national media and allies in all parties, including Ricardo Lombana.

In May 2024, Panamanians will have to choose between a return to authoritarianism, a crumbling status quo, and a new economic model.