Before every European Parliament (EP) election there is a lively discussion about the European Union’s drift to the right. Three brief caveats about the EP need to be made at the outset. First, the Parliament’s power is quite limited. Second, ideological and programmatic proximity does not necessarily mean good cooperation, even and especially for the far right. And third, national power configurations repeatedly get in the way of the parties’ political aims at the European level.

Jan Rettig lives and works as an activist, lecturer, and coordinator of a local partnership for democracy in Bremen.

But who are the right-wing parties in the EP and what do they want?

Mapping the Spectrum

Let us first briefly categorize the far right spectrum of the current EP, slightly across the political factions, but along comparative developments that are very much determined by respective national contexts.

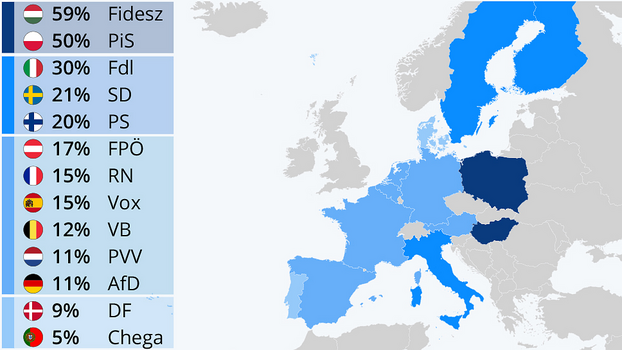

Leading the way among the recent successes is the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) in Germany. Some of their European counterparts needed three to four decades to accomplish the rise they managed within the last ten years. With attitudes ranging from EU scepticism to hostility, the AfD was rather haphazard in the EP in practical political terms, which meant it has not yet been integrated into European networks. This will probably change now with their recent resolution to join to European party Identity and Democracy (ID).

Just as recent and even more successful are the heirs to Spanish and Italian fascism: Vox and Fratelli d’Italia. Despite their ideological proximity to the ID parties, they are oriented towards the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) parliamentary group and party. This is in contrast to the Estonian Eesti Konservatiivne Rahvaerakond (EKRE), which has been a faithful member of ID since entering the EP in 2019.

Their national importance makes the last three parties part of a second large cohort of parties that are governing, have governing experience, or are close to a government. They are significantly different in their orientation within their faction. While participating in a national governing coalition, the Lega in Italy and Austria’s Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ) positively and actively made reference to the ID as the core of a far-right European alliance. In contrast, Poland’s Law and Justice (PiS) and the Hungarian Fidesz kept their distance from the ostensibly more radical parties. Immediately following their electoral success in the spring of 2023 (and before subsequently joining the governing coalition), Finland’s Finns Party left ID and re-joined the ECR group. For its part, the founding member Nacionālā apvienība (National Alliance, NA) has been a member of the Latvian government since 2014. By contrast, the Danish People’s Party (DF) has never been a part of the Danish government, but through its support of minority governments, it has been quite willing and able to push through anti-immigration “realpolitik”. Its liberal-conservative origins allowed it to align with various EU-sceptical factions in the past. Then, in 2019, it was one of the initiators of the ID.

It was there that the DF joined up with the truly unrelenting parties, who have also remained excluded from participating in a national government so far. The electoral success of the Rassemblement National (RN) over the last 30 years, its expanded social programme and its strategy of “de-demonization” still have not sufficed for a mandate in the French national government. The French system of majority voting is partially responsible, but with the presidential elections, it is first and foremost due to the left-wing, liberal, and conservative preventative alliance that has been repeatedly activated again and again in the run-off vote.

The desire for leadership and submission increases in times of crisis — a potential that has not been completely exploited by the Right so far.

Due to the rules of mandatory proportional representation in the EP, the RN has long been strongly represented and alliance-oriented. However, it did not play a leading role in the past legislative period because of misappropriation of funds, internal disputes, and the departure of several MEPs. This will probably change again in 2024, when the RN is expected to constitute the largest far-right EP delegation by a large margin. The Belgian-Flemish Vlaams Belang (Flemish Interest, VB) has been equally obstinate and not a member of a government to date. Following its massive advances in the 2019 Belgian parliamentary elections, public debate had been dominated by concerns that the political cordon sanitaire could soon dissolve there as well. In the EP, it has stood steadfastly with the RN since the beginning.

The relatively small newcomers have a different experience in common. In 2019 it was expected that Sme Rodina (Our Homeland) would join the EP for Slovakia, but it narrowly fell short. Yet it joined the ID party and has a good chance of sending MEPs in 2024. In Portugal, Chega (Enough), which was only founded in 2019, was irrelevant for the last EP election, but will surely clear the hurdle this time around. It is also already a member of the ID party. Although the Czech Svoboda a Přímá Demokracie (Freedom and Direct Democracy) has stayed off the radar so far, it has been in the EP for some time and has been in the ID faction since its foundation.

All of these parties have become established members of the opposition in the lower and mid-levels in their respective national contexts. This is also true for the Greek ethnic-nationalist Elliniki Lysi (Greek Solution), but it appears to be aiming for respectability in the ECR group.

The Hungarian and Greek neo-Nazi parties, Jobbik and Golden Dawn, are out of contention and do not belong to any faction. Two Slovak MEPs were originally elected to represent the neo-Nazi party Kotlebovci in the EP, but have since left that party or distanced themselves and are now representing the equally far-right parties Republika and Slovenský Patriot.

Not Business as Usual

The European far right achieved historic results in the 2019 EP elections, making up nearly a fifth of MEPs since then. At the time, the Lega was still part of the government in Italy, the FPÖ had just left the government in Austria, and the EKRE had just joined the national government in Estonia. Accordingly, the far right was quite self-confident at the European level.

While not fulfilling Matteo Salvini’s stated goal of ruling, with 73 MEPs, ID formed the largest explicitly far-right group since the EP’s foundation. It emerged seamlessly — which is not to be taken for granted on this part of the spectrum — from its predecessor, the Europe of Nations and Freedom faction, and added several smaller parties. The ECR group, which is considered comparatively moderate, also managed to continue, although it was weakened at the beginning. The Perussuomalaiset and the DF had left for the ID group and the British conservatives also had to leave later on. However, Vox and Fratelli then joined ECR, along with PiS and the Sweden Democrats (SD).

Fidesz spent the legislative period without belonging to a faction. The authoritarian restructuring of the state and various discriminatory policies in Hungary proved to be incompatible with the Christian-conservative family of parties. Initially suspended from the European People’s Party (EPP), it then left that faction and party in early 2021, shortly before it could be expelled.

The Brexit Big Bang

The current legislative period was partly marked by unexpected ruptures that presented ideological and policy challenges for the European right wing. The historical aspect: a member state left the EU for the first time. Great Britain’s departure was preceded by various (frequently extended) negotiations, which had been initiated by the British referendum back in 2016. However, the political aim of EU withdrawal had already been launched in the early 1990s with the establishment of the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP), later called the Brexit Party.

The times seem favourable for the Right — they are the children of certain circumstances and the circumstances are currently forgiving them almost everything.

UKIP, and its charismatic leader Nigel Farage in particular, have been present and well-connected on the European stage since the end of the 1990s. While UKIP’s collection of anti-EU MEPs coalesced under the faction name Europe of Freedom and (Direct) Democracy, ultimately they turned their back on the parliamentary plenum in demonstration during the EP’s opening session in 2019, before rather unspectacularly withdrawing from the EP at the beginning of 2020. Their concrete success turned them into far-right pioneers.

Each of the specific discussions of EU withdrawal were animated by projections of the possibility of sovereign action by nation states. However, this does not mean that there is consensus on the matter or on the assessment of its economic consequences. In the case of the AfD, a widespread antipathy towards the EU was formative for its identity since its establishment in 2013, but it still did not explicitly include a German exit from the EU in its platform until the beginning of 2021, which it diluted for the 2024 EU election campaign. The RN dropped the French exit in 2019, and its EU discourse has since slipped into the background.

If a far-right party enters government, exiting the EU is a very low priority. In Italy, for example, neither the Lega in the past nor the Fratelli in the present have pursued the goal of navigating the country out of the EU despite their sovereigntist speeches and anti-EU rhetoric. There were no such attempts during the last of the FPÖ’s stints in the government in Austria, and nothing more was heard from the EKRE, NA, or the PiS in this regard either. Ideologically, the PiS is firmly oriented to the West and so also to the EU — despite all its recalcitrance. The Finns Party is slightly out of step because it is pragmatically postponing a Finnish exit due to the current Russian threat.

The Political Consequences of the Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic also started spreading throughout the world at the beginning of 2020, constituting a true litmus test for a globalized world society. It was followed by drastic social and political measures from mask mandates to lockdowns. The spectrum of right-wing responses was extremely broad, ranging from denial to acknowledging the virus and from rejection to support of the measures taken.

Yet at no point was the diversity of positions within the ID cause for disputes or division. There was good reason for this, because the main pandemic measures came very close to right-wing political ideals — like the wide-ranging restriction of free movement and the reintroduction of border controls for individuals on almost every internal European border, closing off to the outside (incorrectly called the suspension of Schengen, as goods and capital were spared) and the sovereign national determination of infection protection measures and economic stimulus packages.

In this way, the measures revealed an anachronistic, reactionary understanding of politics, whose horizon of possibilities consisted in social segregation, geographic isolation, and reinforcing national borders. To this was added an increased need for authority, which was also expressed through increased trust in the pandemic policies of governments in power (regardless of their position on the political spectrum). As we were able to see, the desire for leadership and submission increases in times of crisis — a potential that has not been completely exploited by the Right so far.

The Perpetual Issue of Migration

For decades, the most important issue for the right wing has been global migration. The European regulation on asylum and migration management, which is currently being debated, marks a restriction of the processes of examining and rejecting asylum claims, calling for a more strict distribution of tasks and costs across Europe. The first element is a basic concern shared across the far right. However, the second is also a cause of dissatisfaction for some groups.

Opposition from Fidesz and PiS is primarily directed towards the redistribution of refugees and mandatory compensation payments. On the other hand, Fratelli first and foremost wants to achieve a redistribution of refugees (away from Italy) due to predominant migration routes at present. This leads to the absurd situation in which a post-fascist Italian prime minister has to negotiate with her right-wing counterparts from Poland and Hungary on a European asylum law that is fundamentally right-wing.

Anti-immigration policies are simultaneously being enacted on many levels. To name just a few examples: fences are being built on the Hungarian border under the aegis of Fidesz, and self-appointed neo-Nazis are patrolling the German-Polish border. The fascist Identitarian movement is issuing calls to fight rescue operations in the Mediterranean, producing effective propaganda, while SD chairman Jimmie Åkesson is handing out flyers at the Turkish-Greek border with the message that immigrants should stay away from Sweden.

The War against Ukraine

The war against Ukraine presents an incomparably more difficult challenge. The Maidan protests, the Russian annexation of Crimea, and the secession of two “people’s republics” in eastern Ukraine had already exposed a fundamental fault line within the European right wing since 2013–14. At the time, foreign fascists participated in the fighting on the Ukrainian as well as the pro-Russian or separatist side.

These differences are reflected in contemporary parliamentary discourse. Almost all parties belonging to ID and ECR have formally spoken out against the Russian attack on Ukraine. Old ties and connections only become clear through subtexts and relativization. For instance, the RN is still repaying a Russian loan from 2014 — corporate acquisition means the money now goes to a defence contractor. Matteo Salvini’s behaviour demonstrates that the Lega is taking its friendship agreement with the Russian ruling party United Russia seriously. The FPÖ’s ties to Russia are well-known, the AfD has lost most of its so-called transatlantic members and a majority of its members take pro-Russian positions, although this is now shrouded in the discursive strategy of formally condemning the attack on Ukraine as a violation of international law.

In the current situation, being an MEP for the most far-right groups is clearly not so attractive and offers very little in the way of strategic prospects.

There is a clear fault line between the aforementioned positions and a large portion of the Eastern European right wing, most of all Poland, as well as the updated anti-Russian anti-communism espoused by Vox and Fratelli.

The Finns Party’s support for Finland’s bid to join NATO was likely the reason for the party leaving the ID group, which is at least tolerant of Russia. Depending on the development of Russia’s power and potential as a threat, it might not be possible to repair this rift in the foreseeable future. However, since the beginning of the Ukraine war, approval ratings for Russia and Vladimir Putin have decreased markedly with right-wing voters across Europe, which is likely related to the war.

Prospects

First and foremost, it is certain that the EP elections in June 2024 will bring with it further growth for the political Right. The number and proportion of far-right representatives in the EP has been increasing for decades now. The times seem favourable for the Right — they are the children of certain circumstances and the circumstances are currently forgiving them almost everything. Right-wing groups may formulate contradictory and incorrect answers to global economic and social challenges, but there is currently little sign of left-wing alternatives that could stand up to them.

Second, the right wing itself is shifting. The ID group has already lost a sixth of its MEPs during the current legislative period. In the lead-up to and during the 2022 French presidential campaign, four MEPs from the RN switched to Reconquete!, the party behind Éric Zemmour, a proven anti-immigration and Islamophobic racist, nationalist, and historical revisionist. They have not belonged to a faction since then. The Lega lost three representatives to Forza Italia and one to Fratelli, which was only an intra-family shift from the perspective of national government. However, the Lega’s support also declined significantly in Italy and it will no longer be the largest constituent in a faction succeeding the ID.

The Dutch Party for Freedom (PVV), or more specifically their MEP Marcel de Graaff, who switched to the Forum for Democracy (FvD), was the only departure due to differences over Ukraine. As with the Finns Party, it was only a lightweight in terms of numbers. However, the resignations of the two representatives meant the ID only barely met the country quorum for forming a faction.

On the other hand, the ECR group, which had been seen to be on its deathbed, managed to stabilize in two respects, and at a high level at that: member parties such as Vox and Fratelli have become significant or even governing parties in their respective national contexts, and with their expected positive election results in 2024 they will further expand the relative share of the far right in the ECR group. This is also true, albeit with lower representation, for the MEPs from the Baltic and Scandinavian right wing, which are strategically oriented to the ECR.

Third, these power shifts within the right-wing camps are interesting because they are positioning themselves not so much along ideological lines, but through realpolitik power alliances. Even if independent policies have only been formed to a limited degree on the European stage, a strong combining of certain interests or shared enemies may well be able to disrupt the political process at this level. The more that strong party delegations coordinate (as factions) in the EP and the more they are simultaneously involved in other EU bodies such as the Council of the European Union and the European Council (as representatives of national governments), the more effective they will be. The EP has been affected by the increasing fragmentation of many national party systems for some time now. In 2019, the Christian and Social Democrats no longer had an absolute majority for the first time since the EP’s founding.

Fourth and finally, despite various unknowns, there appears to be several relatively solid determinants behind the right wing’s internal restructuring — first and foremost, the now long-standing ties between the RN, the Lega, Vlaams Belang, and the FPÖ. It seems as if hardly anything can tear them apart, neither Ibiza nor corruption scandals, nor differing positions regarding the pandemic, nor Ukraine. However, the ID faction only had departures during the past legislative period, with the exception of the PVV, which received several new MEPs due to the post-Brexit redistribution and which was already part of the clique.

In the current situation, being an MEP for the most far-right groups is clearly not so attractive and offers very little in the way of strategic prospects. The fact that various MEPs left to join their national parliaments and the corresponding filling of spots with replacements gave the faction the appearance of a constantly revolving personnel carousel. In doing so, they constantly relativize the relevance of the EP, despite their projections and claims.

In many respects, the Visegrád alliance of Poland, Hungary, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic is quite focused on national politics. While they are united on economic issues and immigration policy, and support each other in the EU’s rule of law proceedings, they diverge in terms of foreign and security policy. Fidesz has repeatedly sought to develop positive connections with Russia, while the PiS has done the same with NATO. It appears increasingly unlikely that these two heavyweights will join the same parliamentary faction.

This means that a right-wing “super-faction” is also unlikely to emerge after 2024. What is more likely is a larger, internally differentiated landscape of right-wing factions, within which a large number of MEPs will receive financial and infrastructural resources to advance their reactionary and inhumane agendas.

Translated by Bradley Schmidt and Marty Hiatt for Gegensatz Translation Collective.