The Left recently caused quite a surprise in Spain. On 23 July 2023, early elections were held to elect a new parliament (congress of deputies and senate) and while the polls predicted a clear victory for the right and the far right, the social-democratic left and the radical left managed to beat the forecasts. The left- and right-wing blocs were very close in terms of voting percentages and it is not yet clear if a government will be successfully formed or whether new elections will have to be called. On 22 August, King Felipe VI asked the leader of the conservative right, Alberto Núñez Feijóo, to form a government, despite the fact that he does not currently have the required majority.

Laura Chazel is an associate researcher at Sciences Po Grenoble, a research fellow at the Research Institute for Sustainability of Potsdam, and a post-doctoral researcher at Jagiellonian University in Krakow.

In 2015, the Left-Right divide seemed to fade from prominence in Spanish political life, only making a return in 2018. What has first emerged from these elections, however, is that — contrary to other European countries — the left-right divide seems to be structuring Spanish political life once again. This has led some commentators to claim that “Spain’s two-party system is back”. Spain is currently divided into two blocs — left-wing and right-wing — and these two blocs confront one other on a number of structural issues, including the economic and social responses to the various crises affecting the country (e.g. investment policies or orthodox economics), the political system (e.g. the issue of the monarchy — which also divides the Left), the place of peripheral nationalisms (e.g. the Catalan issue), the country’s history (e.g. the memory of Francoism), and “societal” issues and individual rights (e.g. LGBT-related issues and women’s rights).

The general elections were originally scheduled for the winter of 2023, but were brought forward after the prime minister and secretary of the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE), Pedro Sánchez, decided to dissolve Parliament. This decision followed the poor results of the Left and the victory of the Right in the municipal and regional elections of May 2023, in which Feijóo, President of the People’s Party (PP), sought to “repeal Sanchism”. The general elections occurred in the context of a government that had been in place since January 2020 and which was made up of the social-democratic Left, represented by the PSOE, and a radical Left coalition consisting of Podemos and Izquierda Unida (IU), known together as Unidas Podemos (UP).

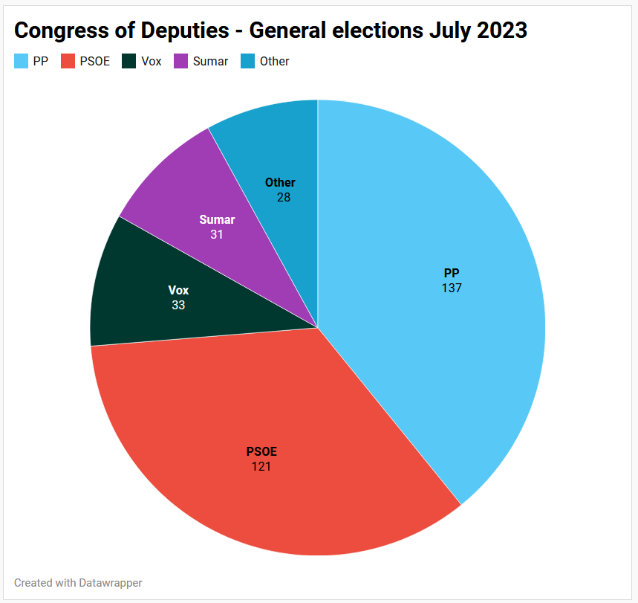

The Right took the most votes, while the left-wing bloc — composed of the PSOE and Sumar — failed to secure an absolute majority in parliament. Still, Feijoo’s gamble cannot yet be considered an out-and-out victory. The PP may have obtained just over 33.05 percent of the votes (as compared to 20.81 in 2019), but it was closely followed by the PSOE, which beat the polls by coming in second with 28.12 percent (as opposed to 28 percent in 2019). Vox, the far-right party led by Santiago Abascal, came in third with 12.39 percent (15.08 in 2019). The radical left-wing party, Sumar, took fourth place with n12.31 percent (12.86 for UP in 2019) and was represented for the first time by Yolanda Díaz, Second Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Labour and Social Economy in the Sánchez government. As has become usual since the rise of Podemos and Ciudadanos and, with them, the end of Spain’s two-party system in 2015, the outcome of the election is now uncertain.

The aim of this article is to analyse the different actors on the Spanish Left, especially the PSOE and the new political movement Sumar that emerged in 2022. The analysis will be framed within the context of (1) the policies implemented by the Spanish centre-left government, particularly Sánchez’s second government which took office on 13 January 2020, and (2) the outcome of the 2023 general elections.

Spain’s Left Government

In this first section, we take a brief look back at the context in which the general elections of July 2023 took place.

The Resilience of Social Democracy

Despite the rise of Podemos in the general elections of 2015 (20.68 percent), the PSOE managed to maintain its control on the leadership on the Left (22 percent). In 2018, Pedro Sánchez became Prime Minister following a vote of no confidence in the government of Mariano Rajoy (PP). The general elections of 2019 confirmed and accentuated the hegemony of the PSOE on the Left, with the party obtaining 28.67 percent of the votes in April (14.32 percent for UP) and 28 percent in November (12.86 percent for UP).

Events in Greece and France have reinforced the notion of the “end of the social-democratic century” with the collapse of the Pasok in favour of Syriza in Greece and the collapse of the Socialist Party in favour of La France Insoumise (LFI) in France. Events in Spain, however, rather suggest the continued resilience of social democracy, which is particularly noteworthy given the austerity policies implemented following the 2008 crisis and the increasing distrust in “governing parties”, both of which render the context, at least at first glance, rather unfavourable.

The Rise of Vox

Having opposed the PSOE (a contraction of the PP and the PSOE) in 2014, the leaders of Podemos agreed to form a coalition government led by Pedro Sánchez in 2018. This rapprochement between Podemos and the PSOE can be explained by the PSOE’s shift to the left and by the emergence of a bloc logic in the party system.

This, in turn, is due to less polarization on the Left, which is faced with the rise of the neo-Francoist threat represented by Vox. Lluís Orriols and Sandra León distinguish between two periods in this regard: the first period, from 2015 to 2017, saw an increase in competition between Podemos and the PSOE that could be seen in the “high levels of affective polarization” between the two parties and which prevented any transfer of votes from one to the other. The second period, from 2018 to 2020, saw a decrease in “intra-left polarization” and an increase in “inter-bloc polarization”.

The Right took the most votes, while the left-wing bloc failed to secure an absolute majority in parliament. Still, Feijoo’s gamble cannot yet be considered an out-and-out victory.

The literature on this topic has long highlighted the existence of “Spanish exceptionalism” in terms of the absence of the extreme Right in party politics. This exceptionalism could be explained by the longevity of the Franco regime (1939–1977), which discredited this family of parties. When Podemos was founded in 2014, the radical Right was represented by Vox, which had been founded the previous year and was, at that point, quite weak and marginal.

However, from 2018 onwards, Vox grew more successful following significant electoral inroads made during regional elections in Andalusia. The party “[combines] nationalism [and] xenophobia” with “an authoritarian vision of society, attached to the values of law and order.” When it comes to the rise of the far right, Spain has been rather unique as compared with other European countries. Vox’s electoral breakthrough was not linked to the issue of immigration, but to the Catalan crisis in 2017. Concerned with issues “relating to decentralization, probably generated by the Catalan separatist crisis”, Vox voters were fiercely opposed to Catalan independence.

Led by Santiago Abascal in the 2019 general elections, Vox entered Parliament for the first time, winning 10.26 percent of the vote in April (24/350 MPs) and 15.08 percent in November (54/350 MPs). The party overtook Unidas Podemos to become the country’s third-most significant political force. These events shattered the notion of “Spanish exceptionalism” and put an end to the long-held belief that “Spain had seemed immune from the rise of far-right forces” following the end of its authoritarian regime in the late 1970s. Now in coalition government with the PP, a “mainstream” political actor, in several cities and regions, Vox has become an integral part of the political system.

The Left Coalition and a New Left Leader

Since 13 January 2020, a coalition government consisting of the PSOE and Unidas Podemos has been in place. The latter has had five members in the council of ministers, including: Pablo Iglesias (leader of Podemos from 2014 to 2021) as Second Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Social Affairs; Irene Montero as Minister of Equality; Yolanda Díaz as Minister of Labour; Manuel Castells as Minister of Universities; and Alberto Garzón (leader of the IU) as Minister of Consumer Affairs.

On 4 May 2021, Pablo Iglesias abruptly announced his retirement from party politics following the disappointing results of the 2021 regional elections in Madrid. Yolanda Díaz, a member of the Communist Party of Spain (PCE) and a former member of Izquierda Unida, then succeeded Iglesias as Second Deputy Prime Minister. Iglesias’ departure left a political space for a major political recomposition and the advent of a new political leader to the “left of the Left”. Yolanda Díaz filled this leadership position, partly thanks to her popularity as Minister of Labour.

On 8 July 2022, Díaz officially launched a new political initiative, Sumar, which she intended to represent in the 2023 general elections. At the launch, which was attended by almost 5,000 people, Sumar was presented as a citizens’ movement that any left-wing organization could join. Díaz’s ambition was to bring together organizations that had been presented as irreconcilable such as Podemos and Más País (MP), represented by Íñigo Errejón.

At the same time, Sumar distanced itself from the radical left political leaders who had emerged since 2014, and stated a desire not to become “a soup of acronyms” but a citizens’ movement capable of building “a new social contract”. This desire was reflected in Díaz’s rhetoric, in the aesthetics of the meeting for which no political party symbols were on display, and in the choice of speakers, which consisted of prominent figures from civil society. Since July 2022, leaders from the IU, the MP, and from Podemos have all demonstrated a will to ally themselves with the project and support Yolanda Díaz’s candidacy, due in large part to the popularity of Díaz herself.

Since the beginning of Díaz’s initiative, each of the radical left-wing organizations have differed in its relationship to Sumar. For example, Izquierda Unida — which has been part of the Unidas Podemos coalition since 2016 — has welcomed the initiative from the outset, and declared itself intent on becoming fully involved. The main leaders of Más País, which formed after a split with Podemos in 2019, gave Sumar their support, although this may have been partly due to the poor prospects of their leader, Íñigo Errejón, in the 2023 general elections.

Podemos has clearly been the party most reluctant to ally itself with this project. Although Iglesias himself had nominated Díaz to succeed him as vice-president of the government, tensions between the two political leaders began to rise in autumn 2021. In November 2022, Podemos confirmed its intention to support Díaz’s candidacy with Sumar for the 2023 elections, but at the same time reiterated its desire to survive as a party and to maintain its leadership on the Left. For example, on 6 November 2022, at the Podemos autumn university, Iglesias reiterated that in the process of building a common candidacy “Podemos [had to] be respected”.

It is remarkable, however, that despite the tensions between Podemos and Sumar, the “Left of the Left” ultimately did succeed in presenting a united candidacy for the general elections of July 2023.

Successes and Failures of the Coalition

Since coming to power in January 2020, the PSOE-UP coalition government has introduced a package of anti-crisis measures, along with a series of structural reforms. The PSOE has made a “turn to the left’” which is partly due to the emergence of Podemos in 2014 and the establishment of the coalition government.

The Government’s Anti-Crisis Policies

In response to the various crises that have affected Europe since 2020, the PSOE-UP coalition government has enacted popular and effective measures that have been described by many commentators as a model for the rest of Europe. Indeed, it has deployed massive economic aid in response to the economic and social consequences both of the health crisis that began in January 2020 with the COVID-19 pandemic, and of the geopolitical crisis unleashed by the war in Ukraine as of February 2022. The government has moved away from the logic of austerity that prevailed during the economic and financial crisis of 2007–2008 under Zapatero’s socialist government (PSOE) and which reflected the neoliberal turn taken by social democracy more generally.

In the wake of the 2008 socio-economic crisis, Zapatero’s government was in line with the majority of European countries insofar as it opted for austerity policies in a bid to receive aid from the EU. It implemented a series of reforms that included VAT increase, recruitment freezes, lower public sector wages, and a raise in the retirement age. The neoliberal dogma that prevailed at the time led to a twofold social and political crisis

Indeed, following the great recession, 60 percent of Spaniards considered that the “rich [had] too much power in their country”, while popular perception of politicians became more and more negative, particularly in light of the growing number of corruption cases. In the years following 2008, “Spaniards have considered that “politicians, political parties, and politics” and “corruption” were the most important problems of the country, following only “unemployment and the economy”.

The PSOE’s decisive turn away from neoliberal and austerity policies suggests that they have learned certain lessons since the aftermath of the 2008 crisis. As for anti-crisis measures, various COVID-19 recovery plans — supported in part by funds from the Next Generation EU European recovery plan — have been successfully implemented. The ERTE programme, which was at the heart of the response to the economic crisis that followed the COVID-19 pandemic and involved economic compensation for companies in difficulty, is one such example.

More generally, the government has implemented a number of measures to deal with the cost-of-living crisis, including the windfall profits tax and wealth tax in the energy sector, the tax on large fortunes and the plan to reduce the cost of public transport. Each of these measures was originally proposed by Unidas Podemos and has been enormously successful.

The windfall profits tax and the wealth tax, for example, will each raise up to 1.5 billion euro per year for two years, while the reduction in public transport fares has significantly increased the number of people using public transport. The anti-crisis measures have also included a cap on gas prices, which was also one of UP’s main demands even before the start of the war in Ukraine. With the agreement of the European Commission, Spain and Portugal have been able to cap gas and electricity prices. This “Iberian exception” has enabled Spaniards to benefit from electricity prices up to three times lower than in other European countries. In June 2023, electricity prices still varied significantly from one European country to another, with Spain (15.18 c€/kWh) maintaining lower prices than countries such as the United Kingdom (46.46 c€/kWh) and Germany (37.85 c€/kWh).

Pedro Sánchez’s government has tried to combine investment policies with economic orthodoxy, but resistance within the government from a number of orthodox social liberals may have slowed progress on certain issues.

Among the budgetary measures put in place, the third anti-crisis package announced in December 2022 is also worth mentioning. Amounting to 10.6 billion euro, it entailed, among other things, the abolition of VAT on certain food items, a freeze on rent prices, and a 200-euro voucher for the most vulnerable households.

The Government’s Structural Reforms

Various other important reforms have also been put in place, such as:

- An increase of 8 percent for the minimum wage in February 2023 (a 47 percent increase in five years)

- The housing law in May 2023, the aim of which was to “transform what is now a luxury product into a basic necessity” by regulating, in particular, rents in high tension areas and by penalising landlords who leave several homes empty

- The pension reform, which makes high earners contribute more without changing the retirement age.

- The introduction of a permanent minimum living income in May 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- The 2022 labour reform led by Minister of Labour, Yolanda Díaz, which introduced structural reforms to the labour market, in particular by making permanent contracts the norm and fixed-term contracts the exception. It was the product of lengthy negotiations and considered to be a historic agreement between the government, employer representatives, and trade unions.

Spain is one of the European countries that has responded best to the various crises, with macroeconomic indicators showing that the country has, for example, kept core inflation under control compared with other countries. Indeed, in 2023, Spain was one of the three European countries with the lowest annual inflation rates(2.1 percent), along with Belgium (1.6 percent) and Luxembourg (2 percent), while economies seemingly stronger economies, such as Germany, have continued to suffer from very high annual inflation rates (6.5 percent).

Spain is also one of the European countries with the highest economic growth forecasts according to the Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). The structural reforms (e.g. the labour law) introduced by Yolanda Díaz have also led to a fall in unemployment and an increase in the number of permanent contracts. With the unemployment rate falling from 13.2 percent in July 2022 to 11.7 percent in June 2023, there have never been so many people in employment and affiliated with the social security system.

Overall, the measures put in place by the government have protected millions of jobs and the most vulnerable citizens. Nevertheless, there is still room for improvement, and criticism can be levelled at the various measures that have been put in place. For example, unemployment has fallen but the overall rate remains one of the highest in Europe at 11.7 percent, ahead of both Greece (11.1 percent) and Italy (7.4 percent). Moreover, although general inflation has been contained, the inflation of food prices remains high. Indeed, the inflation of food prices is one of the highest in Europe, with inflation on “oil and fat” products having risen from 28.1 percent in March 2023 (seventh-highest in the European Union) to 15.4 percent in June (sixth-highest in the EU).

Of course, rising food prices directly affect the poorest and this has led to debates within the Spanish Left, with friction between the PSOE and UP building up in terms of how to respond to this food crisis. Unidas Podemos have proposed the creation of public supermarkets, a point which appeared in the programme they presented at the municipal and regional elections in May 2023, and which suggested creating more than 1,000 such supermarkets across the country. In May 2023, Irene Montero (UP) explained the plan as follows: “The price of food urgently needs to be capped and we are proposing to create a public food distribution company, which will guarantee fair prices for those who create these products, i.e. for small and medium-sized farmers, but also for all families who can consume at fair prices.” The issue of interest rates is also pertinent given that private debts continue to be high in Spain. Here too, the most economically vulnerable citizens with variable-rate mortgages are suffering the most.

It is worth bearing in mind that the coalition government remains dominated by the social democratic PSOE. The radical Left, represented by Unidas Podemos, remains a minority within the government and this leads to at least two obstacles as far as possible progress goes. On the one hand, the temporary nature of certain measures could be called into question and these measures could — as has been requested by Unidas Podemos — be made permanent, such as is the case with the plan to lower public transport costs, for example.

On the other hand, more economic and social measures could be put in place to tackle the various structural problems affecting the country, including unemployment and the high cost of living, as well as significant regional disparities and inequalities. These issues could be tackled by way of measures on corporate margins in the retail sector, for example, or by the public supermarkets proposed by Podemos.

Pedro Sánchez’s government has tried to combine investment policies with economic orthodoxy but resistance within the government from a number of orthodox social liberals may have slowed progress on certain issues. For instance, negotiations on the housing law were arduous and it took a long time to bring the law to fruition. There was also contention within the PSOE over the “tax on the rich” that was finally approved in the 2023 state budget and heated debates regarding all the anti-crisis measures proposed by the UP.

One figure who has mounted resistance to a number of progressive measures is the Minister for the Economy, Nadia Calviño, who worked for several years at the European Commission, serving — most notably — as the Director-General for Budget between 2014 and 2018. Her importance to Sánchez’s government can also clearly be seen in her appointment to the position of First Deputy Prime Minister in July 2021.

The Government’s Progressive Cultural and Social Policies

In terms of cultural and so-called “societal” policies, the PSOE-UP government has also been closely scrutinized for the many laws that have been introduced. The law on euthanasia, for example, was approved in March 2021 and allows patients with incurable illnesses to obtain the right to assisted suicide. Spain, thus, became the fourth European country to regulate recourse to euthanasia alongside Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands.

The trans law, approved in February 2023, was also significant. Among others things, the law: prohibits conversion therapies in Spain, authorizes gender self-identification from the age of 16, that is, people can have their name and gender changed on their identity papers by simply making an appointment with the authorities and without having to provide medical reports, creates a system of offences for acts of discrimination against LGTBIQ+ people, which can result in economic penalization up to 150,000 euro.

Another interesting example is the organic law on the integral guarantee of sexual liberty, known as the “only yes is yes” law, which was promoted by Irene Montero and approved in August 2022. The aim of this law — which contained significant legal loopholes — was to “reverse the paradigm” by placing consent at the heart of the judgement when it comes to sexual offences. It also eliminates the distinction between sexual abuse and sexual assault, which effectively means that any sexual act without consent is considered an assault.

The achievement of this latest law must be seen in the context of the consolidation of the feminist movement in Spain, particularly since 8 March 2018 and the “first feminist general strike” in Spain organized by the Comisión 8M, which mobilized 5.9 million people. The years of struggle, the strength of feminist organizations and movements in Spain, and the “feminization” of Unidas Podemos — particularly the change of leadership whereby Ione Belarra replaced Pablo Iglesias as general secretary in 2021 — have certainly helped to put these debates on the agenda and gain acceptance for the “paradigm shift” initially sought by this law.

The coalition government also introduced a law on democratic memory, which was approved in July 2022 and replaces the 2007 law on historical memory. Among other things, the law aims to honour those who had to leave their country for political, ideological, or religious reasons during the Franco era (1939–1975). For example, the law gives Spanish nationality to “those born outside Spain of a father or mother, grandfather or grandmother, who had originally been Spanish, and who, as consequence of having suffered exile for political ideological or belief reasons or for reasons of sexual orientation and identity had lost or renounced Spanish nationality”. The law also stipulates that “knowledge of Spanish history and democratic memory and the struggle for democratic values and freedom” should be taught in schools.

Podemos’s failure to recognize that there could be legal loopholes in the law on consent as well as their decision to adopt an identity-based stance in defence of the political party may have been one of their greatest mistakes.

This “memory law” comes in the context of the many debates that have taken place in recent years around the transition to democracy and the legacy of Franco’s heritage, which have led many commentators to claim that the “the whitewashing of Franco’s regime in Spain must end”.

The Spanish transition to democracy has long been presented as a “success story” because of its supposed pacifism. However, many commentators have repeatedly deconstructed the myths that surround the transition. They have done so, firstly, by questioning the supposedly peaceful nature of the transition and pointing to the extreme violence that marked a period during which, for example 700 political assassinations were committed between 1975 and 1982. Secondly, analyses have pointed out that many heated debates have emerged regarding the Spanish 1977 Amnesty Law born of the transition, which allowed for the amnesty of those responsible for Franco’s crimes. Thirdly, as various commentators have pointed out, the territorial question was not clearly defined in the 1978 Constitution because of the importance of the consensus that prevailed at the time.

This lack of clarity in the constitution was the source of the many conflicts related to autonomist claims and conflicts that have structured Spanish democracy since its birth. In certain autonomous communities on the peninsula, political life is so polarized around the issue of autonomy and/or independence that many commentators have attested to the existence of several “electoral Spains”. The country has one of the most decentralized states in Europe, with autonomous communities holding significant power. This has led to the emergence of numerous nationalist, autonomist, and regionalist political parties.

The deterioration in relations between Madrid and Barcelona in recent years highlights the limits of the “Spain of autonomies”, an institutional formula inherited from the democratic transition that proclaims both “the indissoluble unity of the Spanish nation” and “the right to autonomy of the nationalities and regions that constitute it”.

Since 2008, the question of Catalan independence has returned to the centre of the debate, with a new electoral impetus for pro-independence Catalan parties on both the left and right of the political spectrum. On 1 October 2017, the pro-independence Catalan government formed in January 2016 held a referendum on Catalan independence, the legal validity of which the Spanish government did not recognise. Against a backdrop of calls from anti-independence parties not to take part in the vote and a participation rate of 42.4 percent, those in favour won by a huge margin (90.18 percent). The referendum was followed by a series of arrests and police searches on the premises of pro-independence elected representatives and senior officials. Among the sentences handed down, the supreme court convicted nine pro-independence leaders for their role in Catalonia’s “secession attempt” with sentences from nine to 13 years imprisonment.

It is in this context that the PSOE-UP government has enacted important measures to pacify the dialogue with the Catalan pro-independence movement, most notably with:

- The “repeal of the offence of sedition and reduction of sentences for Catalan pro-independence leaders who were figures during the illegal referendum held in Catalonia in October 2017” (derogación delito de sedición) thanks to which sedition becomes an “aggravated public disorder” that carries reduced prison sentences.

- Partial and conditional pardons for Catalan pro-independence prisoners.

Although the Right has historically been more resistant to autonomous claims than the Left at the national level, the PP is not a fervent opponent of Spain’s autonomies communities. However, in light of the Catalan issue and under pressure from Vox — which upholds the notion of a strong centralized state — Feijóo’s party has recently toughened its stance.

The PSOE and UP are more open to dialogue on the Catalan issue. For its part, Podemos has defended a “plurinational hypothesis” since its very inception. During the 2016 “Catalan crisis”, Podemos called for a dialogue and tried to defend a third option. The party rejected the unilateral declaration of independence as well as the repression of the Spanish state, but also defended the organization of a legal referendum on Catalonia’s independence.

In August 2023, the coalition government once again demonstrated its openness to the “historical” communities when the new president of the congress of deputies, Francina Armengol (PSOE), authorized the use of co-official languages within the congress (Basque, Catalan, Galician, and Spanish).

Popularity of the Government’s Measures

The coalition government’s policies to deal with the crisis have been successful in economic and social terms, particularly in comparison with other EU member states. However, although the government’s main actors (PSOE and UP) have limited the damage and have beaten the polls, they have not been as successful as they could have been in electoral terms, particularly as compared with the conservative-liberal right. Cultural and ‘societal’ issues were decisive in the campaign for the July 2023 general elections. Territorial issues — especially the question of Catalonia — and the law on consent played a very important role. These two issues were extremely politicized by the right and by conservative judges in the case of the “only yes is yes” law.

In Europe today, strong are the temptations of various left-wing leaders and activists to develop a discourse of hierarchization of struggles.

The pre-electoral survey carried out for El País and Ser in July 2023 by 40dB provides important clues to understanding the outcome of the 2023 general elections (see Box 1 below). The survey shows that among the coalition government’s achievements, most social laws were approved by a large majority of Spaniards (minimum wage; unemployment), as were certain “societal” ones (trans law; euthanasia law).

The laws that met with the greatest disapproval were the amnesty for Catalan independence prisoners, the reform of the penal code on the offence of sedition, and the law on consent. Irene Montero’s “only yes is yes” law had the perverse — and obviously undesired — effect of reducing the sentences of some sex offenders, which led Pedro Sánchez to amend the law in April 2023 and apologize to the victims. In June 2023, he admitted that the technical error in the law was “the biggest mistake of his government”. Speaking on behalf of the United Nations, an independent consultant on gender issues and the rights of refugees and migrants, Reem Alsalem, also condemned the law, stating that it “should have been the subject of greater consultation”.

Podemos’s failure to recognize that there could be legal loopholes in the law on consent as well as their decision to adopt an identity-based stance in defence of the political party may have been one of their greatest mistakes.

RESULTS OF THE 40dB PRE-ELECTORAL SURVEY — JULY 2023

When asked to evaluate 13 of the government’s key measures, over 50 percent of respondents said that the following measures had been very good or good: the increase in the minimum wage (60.4 percent compared to 14.7 percent who considered it bad or very bad); the pension reform (52.5 percent compared to 17.6 percent for bad or very bad); the law on euthanasia (51.2 percent compared to 20.3 percent for bad or very bad). The following measures were rather well received: the minimum living income (49.1 percent good or very good versus 22.7 percent bad or very bad); the ERTEs during the Covid-19 pandemic (47.5 percent good or very good versus 21.3 percent bad or very bad); aid and anti-crisis measures during the rise in inflation (42.4 percent good or very good versus 26.2 percent bad or very bad); the labour reform (39.9 percent good or very good versus 26.9 percent bad or very bad); the trans law (39.1 percent good or very good versus 32.7 percent bad or very bad).

More than 50 percent of respondents considered that the following measures had been bad or very bad: the pardons granted to Catalan leaders imprisoned (51.7 percent versus 22.7 percent for good or very good); and the “only yes is yes” law on consent (52.8 percent versus 19.4 percent for good or very good). The following measures were rather poorly received: the memory law (36.5 percent good or very good against 33.7 percent bad or very bad); the housing law (30.2 percent good or very good against 37.4 percent bad or very bad); and the derogation from the offence of sedition for pro-independence Catalan prisoners (23.4 percent good or very good against 43.8 percent bad or very bad).

|

The Election Results: What Future for the Radical Left?

Who Won? Who Lost?

It is difficult to assess which political force is the real winner of the 2023 general elections.

At first sight, it would appear to be the liberal-conservative Right, as represented by the PP who came in ahead of Vox’s 12.39 percent. Having come out on top in both the regional and municipal elections of May 2023, it has further confirmed its gains in recent years to position itself as the main winner of the elections (33.05 percent) and the leading right-wing party.

However, another reading also shows that the PSOE emerged victorious from the elections, with Pedro Sánchez succeeding in his gamble and confirming his ability to accurately read political situations. Indeed, political commentators were dubious about the outcome of the Prime Minister’s “double or nothing” decision to dissolve parliament. It is not unimaginable that the PSOE will manage to form a new progressive government. Moreover, the party has emerged stronger from these elections as it managed to confirm its hegemony on the Left. For its part, the radical left represented by Sumar avoided the haemorrhage that had been predicted, and even if the fear of a strong useful vote for Pedro Sanchez was confirmed, they managed to limit the damage.

One of the PSOE’s major victories was to take the lead in Catalonia, while the pro-independence Left, represented by Catalan Republican Left (ERC) lost half its deputies. The achievement of the Catalan Socialist party (PSC-PSOE) is nothing less than historic. At 34.49 percent, it outstripped Sumar’s 14.03 percent to come take pole position in Catalonia.

Surprisingly, third place was taken by the PP (13.34 percent), closely followed by the ERC (13.16 percent). The three main pro-independence parties failed to reach 30 percent of the votes. This is a significant turnaround and could be interpreted as a sign that the coalition government’s policy of opening dialogue with Catalonia seems to be bearing fruit.

Regarding the other regional left-wing forces, in the Basque Country, the “patriotic Left” coalition, EH Bildu gained ground, with six deputies. The party’s general coordinator, Arnaldo Otegi, has already stated that he would vote in favour of the PSOE forming a government in order to avoid one led by a coalition of Vox and the PP.

Two surveys, the pre-election survey carried out by the CIS in June 2023 and the Cluster 17 survey, provide us with important information on the different electorates. They allow us to look at the social backgrounds of the electorate of the Left.

Two important findings emerged regarding the social bases of each party: (1) the left-right axis is a generational vote (young/left vs. senior/right); (2) the left-right axis remains a “class vote”. Regarding this second point, both surveys confirm that the PSOE remains the hegemonic party among the Spanish working classes.

The CIS survey shows, for example, that among those questioned on “without any commitment on your part, could you tell me which party you are most sympathetic to”, the first answer among working-class participants was the PSOE (27.8), followed by the PP (17.5), Sumar (14.2), then Vox (9.9). These results are confirmed by the Cluster17 survey, which also shows a significant “class vote” in favour of the PSOE.

Moreover, the latter survey does not suffer the disadvantage of having focused part of its campaign on “societal” issues. The result is quite clear: the lower the income, the greater the amount of households voting for the PSOE. Conversely, the CIS survey shows that the more affluent classes prefer the PP (32), followed by the PSOE (20), Sumar (10.9) and Vox (10.6). This result is equally confirmed by the Cluster17 survey, which also shows that the highest incomes vote, first and foremost, for the PP.

The Future of the “Left of the Left”

Evaluating the performance of the radical left in these elections presents a challenge.

On the one hand, with 12.31 percent of the votes, Sumar has not done so badly as compared to a year ago when the polls predicted the “Left of the Left” would be very weak. However, the Sumar coalition — which obtained 31 Members of Parliament — lost MPs when compared to the score of the other radical Left formations in November 2019: 35 MPs for Unidas Podemos; 3 for Más País; and 1 for Compromís.

On the other hand, many divisions exist within the radical Left and its parliamentary group. As a whole, they have, thus, seemed to emerge from the overall sequence rather weakened. A political cycle seems to have closed.

Looking at the recent history of the Spanish radical Left, several cycles can be identified. The first cycle (2011–2013) was marked by the consolidation of citizens’ “tides” and the advent of the 15-M movement in 2011, which called for “real democracy now!” This cycle of “collective effervescence” was followed by a cycle of attempts to institutionalize the movement of the squares with the creation of Podemos in 2014, the aim of which was to “transform indignation into political change”.

The early years of Podemos and its electoral successes were marked by the hope that an alternative left could emerge in Spain on a permanent basis. This second cycle was once described as the “populist moment” given that it seemed at the time as if the left-right axis was being replaced by a people-elite axis with “those at the bottom” facing off against “those at the top”. Indeed, this led to the establishment of a coalition government in 2019 between Unidas Podemos and the PSOE.

Today, social democracy is once again hegemonic on the Left in Spain. The various leaders of the radical Left are adopting a much more defensive stance. Their electoral results have steadily declined, and they no longer have the 2015 “mayorships of change” — such as those won in Madrid and Barcelona — which had been laboratories for the radical Left.

The dominant feeling today is that the future of Spain’s radical Left is highly uncertain. Sumar is a very heterogeneous electoral coalition. Of the 31 Sumar MPs elected behind the candidacy of Yolanda Díaz, ten come from the Sumar movement, five from Podemos, five from the Catalan non-independent radical Left, five from the IU, two from Más País/Más Madrid, two from Compromís, one from the Aragonese Union (CHA), and one from the More for Majorca party (MÉS). It is interesting to note that the Catalan radical Left plays an important role in Sumar, with five deputies from the Comuns.

The 2023 general elections were marked by a major divide between progressives and conservatives, and the government bloc stood as the guarantor of the progress made in the face of a reactionary bloc.

Above all, however, it should be noted that there is no hegemonic party within the coalition and this makes it difficult to imagine what will happen next. In any case, it is likely that there will be a shift in the centre of gravity of the radical left with a clear loss of hegemony for Podemos. The party is losing influence on the national scene and has to deal with its modest place within Sumar as well as the organizational and financial consequences of the debacle it suffered in the local elections. With regard to the latter, Podemos recently launched a major redundancy programme, dismissed more than half of its staff, and closed nine federations.

A look at the history of Podemos may help us to imagine what the future holds in terms of the sustainability of the Sumar movement. While Podemos was criticized for having “betrayed” the spirit of the 15-M movement, Díaz hoped to give power (once again) to “ordinary citizens” by creating Sumar. At the same time, she reused certain “recipes” from the first instance of Podemos, such as a desire for transversality, horizontalism, and, movementism.

Sumar first presented itself as a “citizens’ movement” and it remains to be seen whether the movement will become a traditional political party. In June 2023, Sumar was registered as a political party in order to be able to stand in the elections. Over the medium and long term, Sumar runs the risk of becoming just another party on the political scene, and it would then probably be difficult to continue developing a movementist narrative as Podemos did in its early days.

It is also worth pointing out that while the radical Left managed to achieve some damage limitation in the 2023 general elections, the situation was also very frustrating for Sumar as it is conceivable that the electoral coalition would probably have been able to secure more votes in a less polarized context. Díaz’s stance differs significantly from that of Pablo Iglesias insofar as she adopts a more institutional profile as compared to Iglesias’s more anti-oligarchical attitude. Although Díaz’s profile could appeal to both socialist and radical left-wing voters, she was unable to capitalize on this potential given how polarized the election campaign became. Moreover, the formation of Sumar was so hasty that there simply was not time enough to give due consideration to the intricacies of building a union.

Yolanda Díaz is a political leader with a proven track record in government who could continue to represent the alternative left in the future. Pierre Martin distinguishes, as of 2015, three blocs in European party systems: a democratic eco-socialist left, a liberal-globalizing centre, and a conservative-identitarian right. In Spain today, the democratic-eco-socialist left is largely represented by Pedro Sánchez. Thanks to her profile as a negotiator, the low level of intra-left polarization, and the popularity she enjoys among the electorates of other radical left-wing formations, Yolanda Díaz could certainly hope to replace him.

First, she could attempt to present Pedro Sánchez as the representative of the liberal-globalizing centre. She could, for instance, point out the resistance shown by the PSOE since 2020 in implementing the various economic and social reforms proposed by UP. She could also remind people that the radical Left was initially behind most of the measures that have received so much acclaim at the European level. Second, she could brand the PP and Vox as constituting the resurgence of an authoritarian heritage, a strategy that she used all too well in her impressive election campaign against Vox.

In Europe today, strong are the temptations of various left-wing leaders and activists to develop a discourse of hierarchization of struggles, a narrative defending the “national” worker in the face of globalization, and immigration and “woke” demands of the bourgeois Left. This is the case for such factions as that represented by Sahra Wagenknecht within Die Linke in Germany, or formerly by Djordje Kuzmanovic within La France Insoumise in France.

One of the interesting results of the 2023 Spanish general elections — and one which could be a lesson for the future — is that the PSOE and Sumar chose to fully assume their advances in cultural and “societal” policies during the electoral campaign. The 2023 general elections were marked by a major divide between progressives and conservatives, and the government bloc stood as the guarantor of the progress made in the face of a reactionary bloc.

The PSOE and Sumar have not developed a discourse whereby the “societal” issues of the left-wing urban bourgeoisie are set against the social issues of the working classes. On the contrary, they have taken responsibility for their choices in the face of the right-wing offensive. They have continued to defend progressive values while stressing the importance of putting in place ambitious social measures, and this has in no way affected their electoral results among the working classes for whom — as can be seen above — the PSOE remains the leading party.Looking to the future, it is possible to imagine that Díaz could represent an interesting synthesis of different demands as she is a political leader who is respected by the unions and who can assert her role in the concrete improvement of working conditions for employees, while taking on clearly feminist, LGBTQI, and environmentalist positions.