The terror attacks by Hamas on 7 October 2023 and the ensuing war in Gaza have raised tensions in the Middle East — not just in Lebanon and around the Red Sea, but also in neighbouring Syria. Where does the country, ravaged by thirteen years of civil war, stand in relation to this conflict? Is it a geopolitical actor or merely the playground of regional and international powers? And what effect is the war in Gaza having on the conditions faced by people in Syria?

Syria is a key country in the Middle East. It lies between the spheres of influence of significant regional powers: Turkey to the north, Iran to the east, Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states to the south, and Israel to the south-west. Syria is officially at war with Israel, which has occupied Syria’s Golan Heights since 1967. Negotiations on a return of the land and a peace agreement most recently failed in 2000. Consequently, there is no national border between the countries, but rather a ceasefire line controlled by UN peacekeepers. For decades, the region has been considered stable and safe, for whenever the Syrian regime wanted to increase pressure on Israel, it did so using its nearby allies, the Hezbollah militias in southern Lebanon.

Kristin Helberg works as an author, Middle East expert and presenter in Berlin. Her most recent books are Verzerrte Sichtweisen - Syrer bei uns. Von Ängsten, Missverständnissen und einem veränderten Land (Herder, 2016) and Der Syrien-Krieg. Lösung eines Weltkonflikts (Herder, 2018).

After 13 years of civil war, Syria lies in ruins. Beginning in 2011, a peaceful attempt at revolution turned into a brutal struggle for survival by president Bashar al-Assad’s regime and an armed Islamist resistance, which ultimately mutated into a proxy war. Four countries have a military presence in Syria: Russia and Iran on the side of the regime, Turkey in the north along the Syria–Turkey border, and the United States, allied with Kurdish-led troops in the struggle against Islamic State (IS) in the north-east. Syria is thus the theatre of various regional and international conflicts, waged by both state and non-state actors.

People in Syria have been reduced to living in a state of misery with a lack of prospects for years. More than half of the population has been displaced — 7.2 million within Syria, and 6.5 million abroad. Ninety percent of the population is living in poverty, and as of 2024, 16.7 million are dependent on humanitarian aid — more than ever before. This has only been exacerbated by the impacts of the February 2023 earthquake, a cholera epidemic, and the impacts of climate change in the form of water shortages and drought.

Since February 2020, the conflict appeared to have reached a stalemate, even if violence continued in many places. The war in Gaza has introduced a new dynamic into the complex crisis in Syria and could lead to long-term changes in power relations in the country — to the benefit of the regime and at the population’s expense.

Ten Conflict Zones in Syria

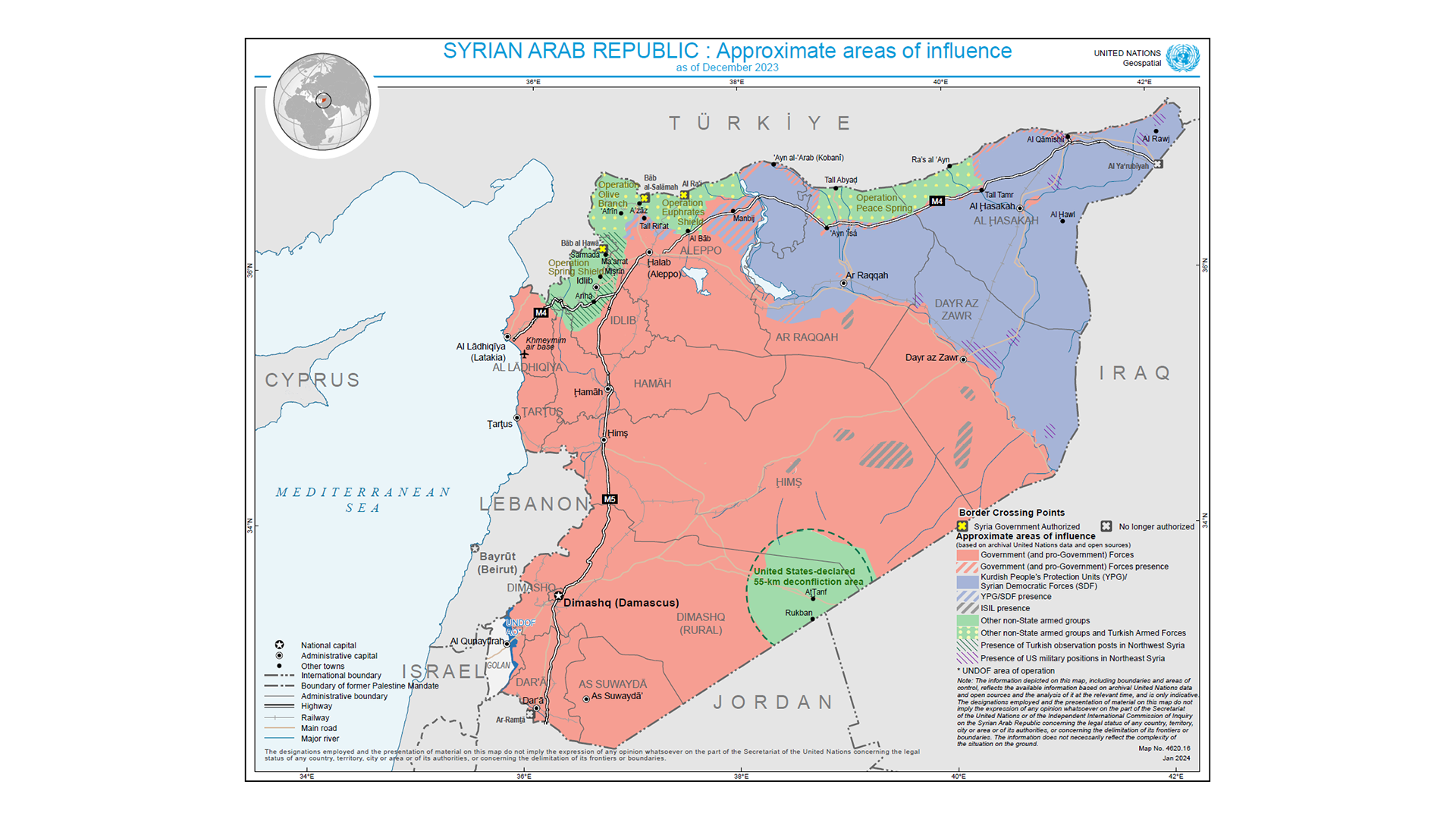

Syria is currently divided into zones of influence. Assad controls the heavily populated areas in the centre, along the coast, and in the south. The north-east — almost one third of the country’s landmass — is governed by the Kurdish-dominated Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES, or Rojava). The final region held by Assad opponents in the north-west province of Idlib is ruled by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), a coalition of extremist militias. Ankara secures the Turkish-occupied regions in the north between Afrin and Jarablus as well as between Tal Abyad (Girê Spî in Kurdish) and Ras al-Ain (Serê Kaniyê in Kurdish) with Syrian soldiers and opposition figures as governors.

Since October 2023, violence has increased significantly in all four parts of the country. The UN Commission of Inquiry for Syria accordingly titled its March 2024 report “Syria, too, desperately needs a ceasefire”. Ten conflict zones can be identified — six internal and four externally motivated.

The six internal conflicts are:

- ongoing government and Russian airstrikes on civil infrastructure in Idlib, with hundreds of civil casualties and 130,000 people displaced, set off by a drone strike on the military academy in Homs on 5 October 2023, causing dozens of casualties, for which no-one claimed responsibility;

- over 50 attacks by the Islamic State (IS) between July and December 2023 on military and civil targets in the centre of the country and in the eastern provinces of Deir ez-Zor and Al-Hasakah;

- confrontations triggered by the August 2023 arrest of a military commander between the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and Arab tribes in Deir ez-Zor, with at least 96 dead and 6,500 displaced families;

- the internal power struggles and human rights abuses of Turkish-controlled militias from the Syrian National Army (SNA) in Turkish-occupied zones, primarily in Afrin;

- the intimidation of civil-society figures and arbitrary arrests by HTS in Idlib province;

- the regime’s continued repression in the form of surveillance, persecution, disappearances, and torture, with the goal of subduing the protests that have been ongoing in the southern province of As-Suwayda since August 2023.

A further four conflicts are driven by the interests of non-Syrian actors:

- Turkish drone strikes in the north-east, which target not only SDF members, AANES politicians, and military bases, but also destroy water works and power plants, oil and gas facilities, and medical infrastructure;

- regular Israeli airstrikes on Iran’s Revolutionary Guards and Syrian military installations in regime-held areas, repeatedly shutting down the Damascus and Aleppo airports;

- rocket attacks on Israel by pro-Iranian militias in the south-west and their more than 100 attacks on US military bases in the north-east, which have led to US airstrikes on pro-Iranian militias;

- Jordan’s military campaign against drug- and people-smuggling networks near the Syria–Jordan border, during which civilians have repeatedly been killed.

This itemization — a kind of chaos list of terror — shows how increasing tensions in the area are fuelling internal power struggles as well as escalating the conflict between the United States and Israel against Iran on Syrian soil.

The Impacts of the War in Gaza on Syria

The war in Gaza is changing perceptions, alliances, and the balance of forces in West Asia, and for people in Syria this has primarily negative consequences.

First, there is a lack of international attention. With the West preoccupied with the wars in Ukraine and Gaza, it is paying scant attention to what is going on in Syria. The Assad regime and Russia and Turkey are using this lack of attention as a licence to pursue their military campaigns in the north-west and north-east of the country.

In light of the suffering in Gaza, people in West Asia are showing solidarity not only with Palestinians, but also with those presenting themselves as their champions: Hezbollah in Lebanon, the Houthis in Yemen, and Iran-led militias in Iraq and Syria. Iran and its anti-Israeli “Axis of Resistance” have thus become more popular, while the United States and Europe, which are considered to be one-sidedly pro-Israel, have lost credibility and influence.

This is helping the regime in Syria, as Assad’s close relationship with Tehran means he is seen to be standing on the “right” side of the conflict. The harsh criticism of Iranian influence on politics, the economy, and society in Syria evident in recent years has significantly waned. In times when Iran’s proxies are standing up to Israel and the US, no one wants to stab them in the back — even if people in Syria don’t want to be dragged into the conflict between Israel and Iran and have little sympathy for Tehran’s Shiite regime.

Russian president Vladimir Putin, Assad’s most important ally, is also benefitting from the escalation in Israel and Palestine. In comparison to the US, Russia, like China, appears to be a more credible mediator between Israelis and Palestinians. By inviting representatives from Fatah and Hamas to Moscow at the end of February 2024, Putin also contributed to inter-Palestinian dialogue, which is essential to resolving the conflict.

Even Turkey, which has been active in power struggles in Syria since 2011, albeit on the side of the opposition, and which has called for the fall of the regime for years, is drawing closer to Assad and his supporters through president Recep Tayyep Erdoğan’s critical stance toward Israel. Regarding Gaza, then, all intervening forces in Syria are in unison — apart from the US, which is thereby increasingly isolated and under mounting pressure.

The Consequences of a Possible US Withdrawal from North-East Syria

With 900 soldiers, the US is protecting the Kurdish-led self-government zone in the north-east from a possible takeover by the Syrian regime and from further ground offences by Turkey. Its actual mission is the containment of IS, which was territorially defeated in 2019 but has seen a resurgence in recent years. Thousands of underground fighters are working toward a restoration of the caliphate, recruiting former fighters in prisons and mobilizing their wives and children in the al-Hawl refugee camp, where 43,000 primarily Iraqi and Syrian IS members are still being held in catastrophic conditions. Of the 6,600 people from other countries in al-Hawl, two-thirds are children and young people, and they are from a total of 47 different countries.

The armed forces of AANES, the SDF, are the most important ally of the United States and its international anti-IS coalition. The Kurdish People’s Defence Units (YPG) constitute the SDF’s largest fraction. Due to their ideological and organizational links to the PKK, Turkey considers them “terrorists”.

The Syrian regime, Russia, and Iran all want to convince the US to withdraw — since July 2023, they have been strengthening their military presence in the east of the country and are using propaganda to create a hostile environment designed to signal to Washington that its troops are in danger. Since October, ongoing drone strikes by Iranian militias on US bases in the region, which in February led to the death of three US soldiers (the first such fatalities), have reignited debate about withdrawing troops from north-east Syria and neighbouring Iraq (where 2,500 US soldiers are stationed). If Donald Trump is elected the next US president in November 2024, a US withdrawal is likely.

The strengthening of the Syrian regime stabilizes a mafia-like network, managed by the Assads, the elements of which cooperate effectively to secure its own survival.

The consequences of a withdrawal for north-east Syria would be dramatic. AANES would collapse, and there seems to be no prospects for an agreement with the regime, as for years Assad has shown no willingness to negotiate a federal structure for Syria. His intelligence services would take control and persecute engaged citizens, journalists, and civil society actors — and thousands would flee into Iraq. IS would use the upheaval to win over supporters. Iran would expand its influence around the Syria–Iraq border and thus open up further supply lines to Hezbollah in Lebanon.

Turkey could come to an agreement with the regime over shared control of the border in return for pulling its troops out of Idlib, which would open the door for the regime to take back the last remaining opposition-held territory. Hundreds of thousands of internally displaced people, which Assad doesn’t want in the country because they’re opposed to the regime, would presumably be corralled into a Turkish-controlled zone on the Syrian side of the border, left to languish without any prospects — a kind of Gaza strip, only without beaches or UNRWA.

The victors would be all those who helped keep Assad in power, securing themselves long-term influence in Syria — Russia, Iran, and Hezbollah — as well as Turkey, which has always pursued its interests in Syria flexibly and decisively.

The biggest losers, meanwhile, would be the Syrian people. The strengthening of the Syrian regime stabilizes a mafia-like network, managed by the Assads, of businesspeople, militia leaders, intelligence services, and the military, the elements of which cooperate effectively to secure its own survival, containing domestic unrest and securing international support. Power is concentrated in the hands of the presidential couple. First Lady Asma al-Assad — a banker who grew up in the UK — secures the economic interests of the regime and her family through a web of businesses, foundations, investment funds, real estate, and land. She has successfully integrated former warlords into the system, thus fending off domestic threats.

The Assad Regime: Stable, but Discredited Domestically and Hamstrung Internationally

Frustration with the extremely corrupt and criminal system is growing among the population, including among supporters of the regime. In the Assad strongholds along the coast, criticism is primarily expressed on social media, while in the southern city of As-Suwayda, thousands of people have been demonstrating for the end of the regime and a political solution to the conflict since summer 2023.

The protests show that the regime’s propaganda is no longer convincing minority groups. The Druze in the south had remained neutral for years, while a majority of Alawites had supported Assad. Now they increasingly hold him responsible for the country’s poverty. For good reason: Assad’s power apparatus is shamelessly and structurally enriching itself from the Western-financed humanitarian aid that flows through the United Nations, its opaque clientelist structures are preventing foreign investment, and it is flooding the entire region with the synthetic drug Captagon. Domestically, the ruling apparatus of the Syrian regime is stable, but socially discredited.

The question remains how powerful Assad is internationally. At first glance, the Syrian ruler appears to be a recognized member of the regional international community once again: in May 2023, Syria rejoined the Arab League, and in November, Assad was among the guests of the its Gaza solidarity summit organized by Saudi Arabia and of the Organisation for Islamic Cooperation in Riyadh. Yet Assad’s rehabilitation largely remains a formality, as hardly any concrete steps toward cooperation have followed from this diplomatic symbolism. This is because Assad cannot give his neighbours what they demand of him: an end to the drug trade and the return of Syrian refugees.

Geopolitically, the Syrian ruler’s hands are tied: he does what Iran and Russia expect him to do.

The Captagon glut is leading to increasing problems in the region, such as drug addiction, smuggling networks, and criminality. Countries like Lebanon and Jordan, which are experiencing their own economic crises, are overwhelmed by hundreds of thousands of Syrian refugees. But the drug trade has meanwhile grown to become the regime’s biggest source of income, and Assad generally considers Syrian refugees to be traitors and enemies. Any real concession vis-a-vis the international community would accordingly threaten his own rule.

There is also the fact that Assad actually has little influence over decisions regarding military and security strategy. When rockets are fired from the Golan into Israeli territory, it is not Assad who decides, but Iran’s Revolutionary Guards. And without Russian anti-aircraft defences, he would be unable to counter Israeli fire on military bases and airports.

Geopolitically, the Syrian ruler’s hands are tied: he does what Iran and Russia expect him to do. In terms of foreign policy, he has ruined his own room for manoeuvre, as his survival depends on Captagon production, embezzling humanitarian aid, and displacing people.

Domestically entrenched and hamstrung internationally, “Assad’s Syria” will further destabilize the region and preoccupy the world as a long-term humanitarian crisis. The war in Gaza will not change the course of such developments, but only strengthen them.

Translated by Marty Hiatt and Ryan Eyers for Gegensatz Translation Collective.