At the headquarters of the Comintern in Moscow in the summer of 1936, an argument unfolded between Najati Sidqi, a Palestinian Arab and member of the Palestine Communist Party, and Khalid Bakdash, the secretary general of the Communist Party of Syria and Lebanon.[1] Bakdash and Sidqi were debating the usefulness of nationalism in the Communist struggle. Sidqi argued that nationalism, and particularly a united Arab movement, could lead to freedom from foreign and imperial domination by uniting Arab toiling masses. Bakdash, on the other hand, believed that nationalism was a backward concept that hindered class consciousness and a Communist revolution in the Arab region.

In the Comintern debate about the issue of nationalism, which had been prominent since the early 1920s, Mao Zedong sympathized with Sidqi’s claim, citing nationalism as an important weapon against colonialism. Georgi Dimitrov, however, disagreed with Sidqi. He decided to send the young Arab communist on an “educational” trip to Tashkent to cure him of his nationalist tendencies by showing him how the Soviet Union has dealt with national identities.[2]

This debate itself—Bakdash and Sidqi arguing over nationalism and Arab unity; Mao and Dimitrov disagreeing over the issue of nationalism and anticolonialism; and Dimitrov using the opportunity to “educate” the young Arab Communist—brings to the fore various contradictions that characterized the Communist International in its short lifespan.

One hundred years after its inception, we are commemorating the Communist International, an organization that promised to “unite the human race”, as the Internationale goes, through the “global idea of the Communist Party”.[3] Yet that humanity collided with certain realities and divisions of the human race, not only along class lines, but also by constructs such as race, gender, and national identity. The Communist International was an experiment whose whole premise was built on forging solidarities that aimed to transcend differences. Yet should the fact that it failed to do so, that it dissolved a few years after its inception, that various schisms occurred within its ranks in its short lifespan, dictate our examination and evaluation of it 100 years after its inception? Should the binaries that the Comintern struggled with throughout its existence—some of which are nationalism/internationalism, East/West, colonizer/colonized, organic or local/borrowed or foreign, success/failure—define its memory and its legacy? More importantly, if we question these distinctions, what lessons can we learn for the current world we live in?

This reflection on the Third International and its relationship with the Levant[4] is in no way a comprehensive account of this history. What I am suggesting, however, is to question these binaries that made up the Comintern experience and to interrogate their “oppositional” nature. Perhaps the only way to escape these binaries is to examine the interaction between these supposed opposites and to problematize that line seeming to separate them. At least for some of those who adhered to this project, these lines were not so clearly drawn.[5] Communists, such as Sidqi and Bakdash, continuously challenged the borders these lines appeared to demarcate.

“The Peoples of the East”: An Entangled Encounter with Capitalism and Imperialism

The age of high imperialism of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries had pushed the semi-peripheral regions of the world, including the Levant, into the modern capitalist order. The Levant’s experience with modernity was therefore an entangled encounter with capitalism and imperialism. Realizing the potential of the colonial question and its intersection with capitalism, the Communist International turned its gaze to the “East” by the early 1920s, particularly following the failure of revolution in Europe. Therefore, from its onset, the Communist International’s encounter with the Levant, and likely with the rest of the colonized world, went beyond the classical framework of historical materialism. Vladimir Lenin spoke not only about the necessity but also about the responsibility of “awakening the East” and the “peoples of the East”.[6] This responsibility, in all its civilizational patronizing tone, positioned the Communist International as the frontier between “the West and the East”. It also placed the Comintern at a higher ground than the “East” within that civilizational hierarchy.

To most inhabitants of the Levant, the nascent Soviet Union was not a part of the “West”, inasmuch as that the West represented imperialism and the colonization of native lands. Rather, it represented a success story of the “East”, an East that could modernize, and most importantly, one that could stand against a viscous Western army threatening its borders and the rest of the world.[7] Therefore, inherent in that binary of East/West was that of colonizer/colonized and oppressor/oppressed. The Comintern prioritized the need to support anticolonial struggles in ‘the backward and colonial countries’ of the East. The internationalism of the Comintern thus became entangled with the fight against imperialism. This explains why the Comintern organized the Baku Congress for the People of the East in 1920 and established an eastern section of the Comintern. It is the reason the Comintern supported and eventually took over the League Against Imperialism, established in 1927 in Berlin as a response to the “other” League, the League of Nations.[8] One of the major pillars of the “Eastern infrastructure” that the Comintern built was the Communist University of the Toilers of the East (KUTV).[9]

Najati Sidqi and Khaled Bakdash were both graduates of KUTV. They both must have taken the same classes in Marxism-Leninism and historical materialism among other topics offered at KUTV. They might have even rubbed shoulders in the hallways of KUTV with Nazim Hikmet, Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit, and others who similarly attended the university. Yet their divergent views on the national question was evident of two things: first, the inability of KUTV (and the Comintern for that matter) to create a uniform mindset about these issues, ultimately proof of the heterogeneity of these categories within the Communist leadership itself; and second, of the different backgrounds and experiences of the two communists coming from Palestine and Syria.

Arab Communist Parties and the National Question

Najati Sidqi was recruited into the Palestine Communist Party (PCP) in 1924 while the party was undergoing a Comintern-mandated “Arabization” process. The PCP had emerged in 1923 out of the fragments of socialist-Zionist groups, particularly the Socialist Workers Party (MPS).[10] The Comintern, fearful to appear in support of the Balfour Declaration and the Zionist project in Palestine, reluctantly admitted the PCP in 1924. The admittance into the Third International was also conditioned upon the party’s denouncement of its Zionist legacy and its recognition of the Arab “national” question. The Comintern continuously demanded that the PCP transform itself into a territorial party that represented the native Arab population and defended the Arab proletariat against Zionism and British occupation. For Arab Communists such as Najati Sidqi, who joined the ranks of the PCP during the period of “Arabization”, the “national” remained a salient framework through which they sought liberation from colonial and capitalist oppression manifested through the Zionist project in Palestine. This in turn explains the PCP’s difficulties in dealing with several important moments in Palestinian history, particularly for that period the incidents in 1929, the Arab revolt in 1936, and the partition of Palestine in 1948.

The national and colonial questions were as important to the history of the Communist Party of Syria and Lebanon. Perhaps the sentiments of one of the party’s main founders regarding Communism and the Soviet Union is most telling of this dynamic. In an interview he gave in 1981, Yusuf Yazbik explained his fascination with Communism at the time as the doctrine that he thought would eliminate “all the evil conditions of the world—poverty, ignorance, exploitation, corruption”.[11] He also argued that the attraction towards the Soviet Union “must be understood against the background of the early 1920s with the West in occupation of the Arab lands and the Soviet Union a revolutionary state extending its hand to the rest of the oppressed world. As young intellectuals disillusioned with the conditions of our society, we enthusiastically grasped the extended hand.”[12]

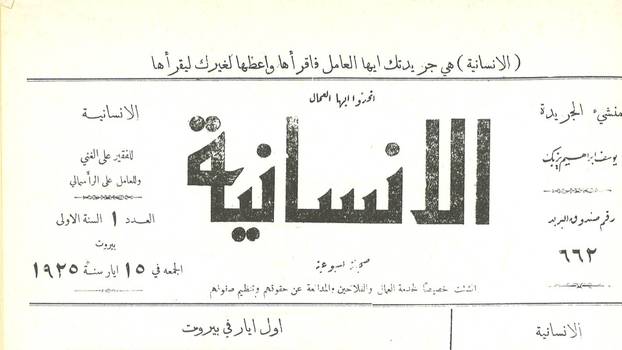

The founding of the Communist Party of Syria and Lebanon (CPSL) coincided with the Great Syrian Revolt in 1925, one of the greatest threats launched against Western occupation of Arab lands during the Mandate period. Supporting the Syrian revolt became the first public campaign launched by Lebanese and Syrian Communists, and the first public announcement of the party came in the form of a declaration demanding Syrian, and ultimately Lebanese, independence.[13] The Syrian Revolt and the national liberation struggle also became a point of cooperation between the Lebanese and Syrian Communists and the Palestine Communist Party, as well as between Communists and non-Communist revolutionaries.[14] The involvement of Communists in the Syrian Revolt begot them similar treatment by French authorities to the Syrian revolutionaries. Beirut prisons swarmed with the main cadre of the CPSL and the PCP, and writings on the prison walls read, “workers of the world unite” and “long live Syrian independence”. Communist cadres and nationalists remained in prison until 1928.

One could argue that these collaborations and overlaps echoed the Comintern’s “united front” line. However, it is important to note that, first, the CPSL was not admitted into the Comintern until 1928. And second, that the blurring of lines between various leftist affiliations and an adherence to a nationalist framework within an internationalist ideology continued to occur throughout the post-1928 period within these Communist parties. This last point is particularly significant since the CPSL witnessed a change in leadership in the early 1930s, when Khaled Bakdash ousted Fuad al-Shamali in 1932 and took the helm of the Communist Party of Syria and Lebanon. He remained secretary general of the CPSL, and later the Communist Party of Syria,[15] until his death in 1995. Yet even Bakdash did not always toe the line as one would expect from the Comintern-trained Communist who had argued against the usefulness of the national framework in 1936. He spent the first few years as secretary general attempting to engage the party and himself with the rising National Bloc in Syria.

“I Have Come to Defend Arab Freedom on the Front of Madrid”

At the dissolution of the Communist International in 1943, Bakdash celebrated the decision and announced, “they said we are associated with an international centre and that we receive our instructions from a foreign power! But now the Communist International has been dissolved and our party has become independent, practically and formally, from any international connection.”[16] He went on to explain that the CPSL was one of the first parties to welcome the decision of dissolution, adding that the independence of the party from the Comintern was in line with its policies to support national liberation and unity throughout its existence. This announcement by Bakdash, shared by the leadership of the Communist Party, coincided with the party’s first engagement in parliamentary elections taking place in Lebanon and Syria in the summer of 1943. The 1943 elections brought sweeping victories to the nationalist elite in both Syria and Lebanon. None of the candidates supported by the Communists won any parliamentary seats; however, the Communists made a surprising showing. Was Bakdash’s take on the dissolution of the Comintern genuine or a crowd-pleasing tactic in the midst of his first electoral bid? While the answer to this question requires more inquiry into this history, what we can ascertain is that the party was indeed facing accusations of foreign affiliation and loyalty that Bakdash sought to refute and hopefully silence.

The conceptualization of Communism as “foreign” and/or “borrowed” was in fact a common trope that evidently even Communists adhered to. If Bakdash had described the Comintern as evidence of dependence on a foreign power, Najati Sidqi questioned the “originality” of Communism in an Arab context. When describing his first encounter with Communism in Jerusalem, Sidqi coined it as “imported principles” linked to Jewish immigration to Palestine from Eastern Europe. This trope and the binary that it creates, foreign/local or borrowed/organic, cannot be understood without the historical context of the Levant’s experience with modernity. It does in fact belong to nahdawi[17] debates and modern Arab intellectual currents that emerged in conjunction with Western imperialism and economic capitalist encroachment. Those who sought to resist the modern world order, in this case through Communism and the international solidarity of the working classes, had to contend with these debates as well. They often straddled different positions and spaces while remaining true to their belief in universal social justice and international solidarities. The same Sidqi who described Communism as “borrowed” willingly stood at the frontlines in Spain and fought in the International Brigades on behalf of the Communist International. In Barcelona in 1936 he declared, “I am an Arab volunteer, I have come to defend Arab freedom on the front of Madrid … I have come to defend Damascus in the Valley of Rocks (Valdepeñas), and Jerusalem in the fields of Cordoba, and Baghdad in Talitala (Toledo), and Cairo in Andalusia, and Tétouan in Burgos.”[18]

The Legacy of the Comintern and Implications for the History of the Left

If we seek to commemorate the Comintern today, we need to commemorate the individuals who made up that organization and believed in it. We need to be willing to recognize the permeability of boundaries that these individuals crossed. We also need to come to terms with the contradictions that the Comintern project presented for the Arab region and the world for that matter, the hopes and possibility of a new world based on social and political justice for all versus the inequalities and hierarchical structures this new world contained.

We have to be able to accept the Comintern as a space that made possible such an exchange by Sidqi, Bakdash, Mao, and Dimitrov, while acknowledging the unequal power relationships that the Comintern carried these individuals into. Perhaps the Communist International could not transcend these differences and its built-in binaries, or perhaps it did. The people who made up this experiment attempted to do so in various ways. The fact that they stood on those boundaries or lines and were witnesses to their absurdity in itself is proof of the possibility of this “new world”. The Communist International, as an idea, an experiment, an organization, and a pedagogical space, should be commemorated not despite of, but because of these contradictions and binaries.

A reflection on the history of the Comintern complicates the history of the Left by breaking the illusion of the uniformity of the Left, its tactics, and its organizations, including the Comintern. This brief reflection on the Third International, which has been mostly remembered as dogmatic and homogenous, reveals that the Left has always flirted with a certain degree of fluidity in defining its parameters and its binaries. This perspective could be useful at a time when the Left, and particularly the Arab Left, is seeking answers to questions of identity, the contemporary practicality of classical frameworks such as historical materialism, and the range of methods available for dissent and resistance.

Dr. Sana Tannoury-Karam is an intellectual and social historian of the modern Middle East. Most recently, she was a post-doctoral fellow in Middle East history at Rice University. She will be joining the Lebanese American University as a lecturer in history in fall 2019.

[1] The author would like to thank Samer Frangie for his constructive feedback on this essay.

[2] See the memoirs of Najati Sidqi that describe this episode and his experience with communism, Najati Sidqi and Hanna Abu Hanna, Mudhakkirat: Najati Sidqi [Memoirs: Najati Sidqi] (Beirut: Mu’assasat al-Dirasat al-Filastiniyya, 2001).

[3] See A. James MacAdams, Vanguard of the Revolution: The Global Idea of the Communist Party, 2017. For a critical history of the Third International, see C.L.R James’s book originally published in 1937, C.L.R. James and Christian Høgsbjerg, World Revolution, 1917-1936: the rise of fall of the Communist International (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017).

[4] I am using here the term Levant (al-mashriq) in its post-World War I context to signify Lebanon, Syria, and Palestine.

[5] For a history of the Arab left that problematizes these boundaries and refutes the homogeneity of the communist movement in the Levant see Sana Tannoury-Karam, “The Making of a Leftist Milieu: Anti-Colonialism, Anti-Fascism, and the Political Engagement of Intellectuals in Mandate Lebanon, 1920-1948”. (PhD diss., Northeastern University, 2017).

[6] Vladimir Ilʹich Lenin, Address to the Second All-Russian Congress of Communist Organization of the Peoples of the East, November 22, 1919 (Moscow: Foreign Languages Pub. House, 1954).

[7] For more on antifascism and Arab Communism, see Sana Tannoury-Karam, “This War is Our War: Antifascism Among Lebanese Leftist Intellectuals”, Journal of World History, vol. 30, no. 3 (September 2019).

[8] For more on the League Against Imperialism, see the forthcoming volume with Leiden University Press,The League Against Imperialism: Lives and Afterlives.

[9] For more on this see Masha Kirasirova, “The ‘East’ as a Category of Bolshevik Ideology and Comintern Administration: The Arab Section of the Communist University of the Toilers of the East,” Kritika 18, No. 1 (2017), pp. 7-34.

[10] For a history of the Palestine Communist Party, see Musa Budeiri, The Palestine Communist Party 1919-1948: Arab and Jew in the Struggle for Internationalism (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2010); see also Zachary Lockman, Comrades and Enemies: Arab and Jewish Workers in Palestine, 1906-1948 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996).

[11] Tareq Y Ismael and Jacqueline S Ismael, The Communist Movement in Syria and Lebanon (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1998), p. 12.

[12] Ibid. For Yazbik’s autobiography on that period see Yusuf Ibrahim Yazbik, Hikayat Awwal Nawwar fi al-ʻAlam wa fi Lubnan: Dhikrayat wa-Tariikh wa-Nusus [The Story of May 1st in the World and in Lebanon: Memoirs, History, and Documents](Beirut: Dar al-Farabi, 1974).

[13] The history of the Communist Party of Lebanon and Syria was first written by the late communist Muhammad Dakrub in Muhammad Dakrub, Judhur al-Sindiyana al-Hamraʼ: Hikayat Nushuʼ al-Hizb al-Shuyuʻi al-Lubnani, 1924-1931 [The Roots of the Red Oak: The Story of the Foundation of the Communist Party of Lebanon] (Beirut: Dar al-Farabi, 1974).

[14] For a first-hand account on this period, see also Fuad al-Shamali, Asas al-Harakat al-Shuyu‘iyya fi al-Bilad al-Suriyya al-Lubnaniyya [The Foundation of the Communist Movements in Syria and Lebanon] (Beirut: Matba‘at al-Fawa’id, 1935).

[15] The Communist Party of Syria and Lebanon became two separate parties in 1943, the Communist Party of Lebanon and the Communist Party of Syria.

[16] A speech by Khaled Bakdash, published in the party newspaper Sawt al-Sha‘b on June 12, 1943.

[17] In reference to the Arabic nahda, or renaissance, of the 19th and 20th centuries. For more on the nahda and these debates see for instance Ilham Khuri-Makdisi, The Eastern Mediterranean and the Making of Global Radicalism, 1860-1914 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010); Dyala Hamzah, ed., The Making of the Arab Intellectual (1880-1960): Empire, Public Sphere and the Colonial Coordinates of Selfhood (New York: Routledge, 2012); Albert Hourani, Arabic Thought in the Liberal Age, 1798-1939, 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983); Christoph Schumann, ed., Liberal Thought in the Eastern Mediterranean: Late 19th Century until the 1960s (Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2008).

[18] Sidqi and Abu Hanna, Mudhakkirāt, 127.