Various years in general beat in the one which is just being counted and prevails. Nor do they flourish in obscurity as in the past, but contradict the Now; very strangely, crookedly, from behind.

Ernst Bloch, The Heritage of Our Times

Contrary to many expectations, interest in the Second World War in Poland has not diminished since joining the European Union in May 2004; on the contrary, the opposite has been the case—no other topic dominates the debates on the politics of memory as much as the period from 1939 to 1945. What’s more, since 2015 the national-conservative government camp has been using the politicization of memory as a welcome means for keeping the electorate in line as part of its efforts to strengthen national identity against the alleged perils of continuing unchecked EU integration.

Basically, leading ideologues of the government camp persistently claim that the country found itself in a hopeless situation after the end of the Second World War because it had been abandoned by the Western victorious powers, as if it had fought on the side of Hitler’s Germany after 1939. When Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki said in 2018 that in the period from 1944/45 to 1989 Poland didn’t even exist, or when the state historical institute IPN (Institute of National Remembrance) is able to officially spread the view that the Second World War first came to an end in Poland in 1989, this indicates the bias with which the current government camp is directing the politicizing of history in Poland.

Holger Politt directs the RLS Regional Office for Eastern Central Europe in Warsaw. Translation by Soliman Lawrence.

And one contradiction stands out: in the course of the quite complicated process of founding the economic community in the 1950s, that later morphed into today’s European Union, great care was initially taken to make sure that the integration was conceived as a solution to the problems that led to the catastrophe of the Second World War; and yet today Poland, who joined the EU in 2004, perceives their membership as a kind of atonement for the “communist era”, which, by no fault of their own, came upon the country as a direct result of the Second World War as a milder form of foreign domination, so that as a result there is now a greater responsibility for the preservation of national identity and the maintenance of national sovereignty. At present, that aims directly at the feared influence of Brussels, which for domestic political reasons are represented as an imposition on the country and as a threat to national identity and sovereignty. Only recently, Poland’s unacknowledged head of state, Jarosław Kaczyński, put it in a nutshell: “When it comes to values, Poland is in a completely different place than many other European countries.” The Minister of Justice Zbigniew Ziobro broke it down even more brazenly: Germany—whose strong influence in the EU is often enough a thorn in the side of today’s official Warsaw—should on account of the Nuremberg Laws and the terror laws in occupied Poland during the Second World War now be the very last country in the world that is allowed to dictate to Poland their judicial culture.

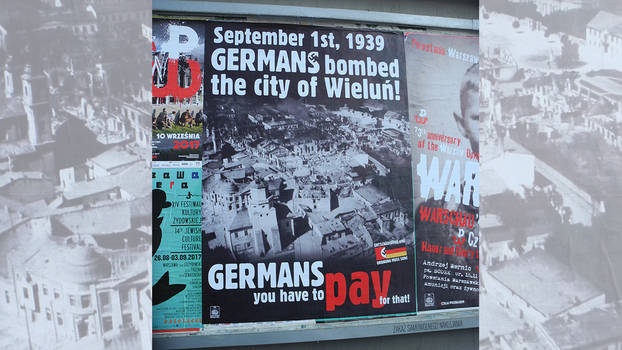

In the EU member countries of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia the period between 1939 and the collapse of Soviet socialism is also used as an argument to rescind certain standards otherwise common in the EU community. A significant example are the monolingual street signs in these countries, even in those particular areas where national minorities make up well over 20 percent of the population. But, for one thing, this concerns an unresolved question in their respective bilateral relations to Russia, because these three republics insist that their existence as a state be recognized since 1918, which Russia refuses to do despite existing diplomatic relationships, instead recognizing the political existence of the republics as of 1991. In this respect, any comparison to the situation with Poland falls short, immediately becoming skewed, that is, unless the current government in Warsaw would like weigh the question of the country’s territorial shape, i.e., call into question the decision by the victorious powers to “shift” Poland about 300 kilometres to the west after the end of the Second World War. This, however, won’t be done for obvious reasons; instead the national conservatives are working diligently to demand high reparations against Germany for the destruction caused and the crimes committed, which they see as still unsettled. When the German side refers to decisions made by the Polish People’s Republic, with which the question of reparations was closed, the argument just cited above is invoked—that at that time Poland didn’t exist and thus couldn’t have been recognized as a legal entity.

Secondly, however, it is apparent that the Baltic republics would merely like to claim specific exceptional conditions for themselves, that is, they don’t want to push their own views on others or enforce them as binding. EU membership is seen in all three countries as a decisive factor in national security, territorial integrity, and thus national sovereignty, and is thus far too crucial to encumber with the complicated specifics of their own particular situations or to be used to play off against one another. Now things are quite different with Poland, for the leaders in Warsaw feel more and more compelled to also prescribe their own understanding of national identity and national sovereignty to the rest of the union, because since the Brexit referendum in June 2016 Poland's national conservatives have been firmly convinced that only a community of sovereign nation states will survive and that the previous path aimed at deepening the integration of the member states has failed.

Although the interests in Warsaw and Budapest overlap to a large extent on this point, such that the governments in Poland and Hungary now agree to seek out and pursue a path of "illiberal democracy", nevertheless Viktor Orbán’s assistance in the great achievement to politicize history will be of little avail to the Polish national conservatives, as Hungary was on the other side of the barricade during the Second World War. In this respect, the primary addressee of the elaborate campaign to politicize history concerning the Second World War and the period of occupation from 1939 to 1945 continues to be their own population. In this way, younger voters in particular are expected to vigorously get behind the political positions of the national conservatives. And the verifiable results show that success is inevitable. Among voters under 30 years of age, the government camp has recently been the most popular of any party in Poland. An important source for this success lies in the politicized handling of the Second World War, with the German occupation, and with the Polish resistance to the occupiers.

«We do not beg for freedom, we fight for it»

One of the most important administrative measures that was implemented in the politics of memory after the national conservatives took office in autumn 2015 was the complete redesign of the permanent exhibition in the Museum of the Second World War in Gdańsk, which was officially opened in 2017. The original concept was based on ideas that originated from the time of the preceding government. This was scrapped in 2017 by Jarosław Kaczyński with the drastic words, that the previous concept of the museum was a personal gift from Donald Tusk to German Chancellor Angela Merkel. In this way, Kaczyński expressed that the museum's previous focus was, first of all, too much in line with how Germany conceives the politics of remembrance, and secondly, that the representation of Polish martyrdom and heroism was being marginalized. In order to achieve the desired restructuring, the Museum of the Second World War was merged with the Westerplatte Museum, which existed only on paper, a new museum director was appointed, in line with the ideas of the governing authorities, and finally the unpopular, albeit finished and internationally acclaimed, original exhibition was scrapped. Now the focus is on easy-to-understand messages that, from the point of view of the ruling national conservatives, leave nothing to be desired in terms of clarity: "We save the Jews", "We were betrayed", "The Pope offers hope for victory", "The Communists lose", "We win", "We do not beg for freedom, we fight for it". If the visitor takes a closer look at the exhibition, they will quickly notice similarities with the thematic approaches in the museums on occupation in Tallinn, Riga and Vilnius. The starting point are the two enemies—Hitler's Germany and the Soviet Union, the intractable struggle and resistance for one’s own national freedom which leads, albeit late, to victory—i.e., to independence and sovereignty.

Like the forest partisans in the Baltic republics, who after 1945 continued to fight militarily, or at least armed, against the Soviet authorities in the hopes that a Third World War would soon break out between the Allies, and who today are held in the greatest national honour, so is this also the case in Poland, as the so-called cursed soldiers have been identified as the real fighters for Poland's freedom and national sovereignty. What is meant by this are those mostly dispersed combat units, that in the autumn of 1944 refused to recognize the capitulation of the insurgent Armia Krajowa (Home Army) to the German occupiers, to lay down their arms, or to be taken into German captivity, but instead continued to fight—less and less, however, against the German occupying forces now retreating westwards, so that the Red Army, moving to Berlin in bloody battles, soon became their only target. And behind the frontline, a long-lasting, bloody civil war-like struggle was incited against the new Polish authorities, who, supported by the advance of the Red Army, had to establish new state relations.

Now the "cursed soldiers" are singled out at the very top of the hierarchy of honourable commemoration; they—as the national-conservative legend has it—fought valiantly and selflessly for what is understood in Poland as freedom and sovereignty and what is now finally being achieved under the national-conservative government. Jarosław Kaczyński regularly speaks of Poland as an island of freedom, which, absurdly enough, implies that there is no freedom around it or that freedom has a completely different character than the kind found on this island.

And the soldiers of the Polish People's Army, who alongside the Red Army liberated the country from the German occupiers and then continued on to Berlin, were the ones who were knocked off their pedestals. The national conservatives will stop at nothing to eradicate the public memory of the Polish army that once fought with the Red Army. This is why an avenue in Warsaw named after the People's Army was summarily renamed Lech-Kaczyński-Avenue on the order of the regional authority, installed by the government, but which was withdrawn this year due to the successful appeal of the city of Warsaw where the democratic opposition is in power. President Lech Kaczyński, who died in an airplane crash in April 2010, was the twin brother of probably the most powerful man in Poland today, who, quite understandably, now feels a special obligation to foster his brother’s public memory.

The Legend of the Warsaw Uprising

A poll on the most important event in the Second World War would in Poland have a clear winner: the Warsaw Uprising, which 75 years ago, began on 1 August 1944. Because the Red Army was within reach of the right bank of the Vistula in the summer of 1944, the Polish exile government in London and the leadership of the Armia Krajowa(Home Army), which was the military arm of the London-based exile government in occupied Poland, decided to liberate the Polish capital from the German occupiers by their own means before the arrival of Soviet troops, because, first off, they were counting on the element of surprise and, second, assumed that the German occupying forces would withdraw from Warsaw sooner or later due to the advancing Red Army. Freeing the capital through their own efforts was supposed to significantly improve Poland's position in the negotiations for the post-war European order, because naturally the exile government was well informed that the future of Poland’s eastern border was going to run according to Soviet wishes, i.e., compared to before the outbreak of the Second World War, it would be clearly shifted several hundred kilometres to the west. The Western Powers—the USA and Great Britain—could have at least convinced the Soviet Union that the composition of a Polish post-war government after the liberation of Warsaw from the German occupation had to be negotiated in earnest with all involved parties. On the contrary, they neither wanted nor could change anything about the route of the future Polish-Soviet border that had been dictated in Moscow. In this respect, the uprising in Warsaw, which was militarily directed exclusively against the German occupiers, was politically a highly controversial issue, since it sought to question the decision that had already been made or rather was foreseeable among the major powers that were fighting against Hitler’s Germany. Furthermore, the London exile camp in effect linked its entire political existence perilously to the success of the Warsaw Uprising. This is also why those in London and Warsaw who were politically responsible for the onset of the uprising hoped for the military support of the Western Allies - for example, through air strikes on German positions—because, as they reasoned, the most loyal ally in the eastern part of occupied Europe would not let down.

Historians have been pointing out for many years that the fate of the uprising was sealed from the start due to the unequal military balance of power. The German occupiers did not flee from Warsaw as expected, but rather quickly directed even more units into the city in order to crush the uprising with all available means. The harrowing numbers testify to the brutality of German advancement: in the weeks of fighting from August to October 1944, over 180,000 civilians died in Warsaw despite not being directly involved in the fighting. Over 20,000 insurgents were killed in the fighting, including above all young people who were often still children. During and after the suppression of the uprising, the German occupiers turned Warsaw’s city centre into a single pile of rubble. The surviving residents were deported from the city into camps. At the very least, the Armia Krajowa (Home Army) was able to ensure through the negotiations of surrender, that the insurgents were treated like a regular army unit, that is, they were subsequently taken prisoner of war by the German authorities and were not executed.

For a long time, the commemoration of the Warsaw Uprising has stuck to the formula that a very special chapter in the recent history of Poland was written by the self-sacrifice of the insurgents and the general bravery of Warsaw in a futile struggle against a brutal opponent with vastly superior military power. On the other hand, however, there was the London exile camp’s catastrophic political miscalculation and the recklessness of the military insurgency leaders in Warsaw, who from the very start knew that the insurgents’ military technology was hopelessly inferior, and for which no single excuse or argument can be given. And finally, military historians regularly point out that the uprising did nothing to alter the course of the war in terms of liberating occupied Europe, despite the enormous death toll. However, as a result, the London exile camp lost its military arm in occupied Poland, leaving the way open for Stalin to carry through his own political goals in liberated Poland.

Nevertheless, in the national-conservative discourse a different, closed narrative is pursued. The failed uprising is subsequently stylized into a victory that has only become apparent today. Without the moral stance of the insurgents and a rebellious Warsaw there would have never been a successful fight against the "communist" era, the Solidarność uprising would never have happened, and Poland and other countries of the former Soviet sphere of influence would not have become members of NATO and the EU. At the time, it was an uprising against the looming consequences of realpolitik, an uprising to fight for freedom on one’s own terms, so as not to have to desperately beg on one's knees before others. In so far as Jarosław Kaczyński understands the current reign of the national conservatives as a time in which Poland finally rises from its knees, and emphatically declares it as such, then the recourse to the Warsaw Uprising is obvious. In this respect, it should come as no surprise that young people in the Warsaw cityscape can be seen wearing T-shirts proclaiming it better to die upright than to live under someone else's thumb. The seeds that were scattered along with the national-conservative conception of national identity and sovereignty seem to grow particularly well in young people.

Thus, it should also be remembered that as late as 1995, Poland voted in an extremely important election campaign with the slogan "We Elect the Future", because the early announcement of admission into the EU offered younger voters in particular a kind of beacon with a fixed course. Aleksander Kwaśniewski, who had successfully led the fledgling Social Democrats out of the defunct state party PVAP into a new era, was surprisingly able to defeat the incumbent and "Solidarność" legend Lech Wałęsa in the runoff election with promises for the future. In Kwaśniewski's conception, history is to be understood as something that is in good hands with the historians' guild, but which can become disruptive to the development of the country as soon as politicians seek to take advantage of it for their own interests, exploiting it as they please, like it was a quarry. Twenty years later in Poland, it appears to be those politicians who voluntarily relinquished the sharp sword of historical politics that appear to be disgraced.

«Pedagogy of Shame»

Jarosław Kaczyński routinely stumbles into what he calls the "pedagogy of shame". As he sees it, this must be eradicated from Poland, for it is a reprehensible and malicious consequence of the far-reaching triumph of German history and memory politics. When it comes to the mass murder of the Jews of Europe in the Second World War, the whole world invariably speaks of the Nazis as perpetrators, of the National Socialists, and yet, he believes, when it comes to those in the occupied territories who participated in the crimes, it suddenly becomes the Lithuanians, Latvians, Ukrainians or even the Poles. This imbalance, as Jarosław Kaczyński announced immediately after the national conservatives came to power in late autumn 2015, must now be remedied by henceforth going on the offensive with Polish history and memory politics. As "pedagogy of shame" he thus understands all efforts to alleviate the role of German guilt in occupied Poland by exaggerating the issue of the guilt of individual Poles. This, he believes, must be categorically repudiated, if the Polish side is blamed for the crimes against humanity in connection with the period of the German occupation. One of the reasons for the fact that Poland now has to strive for its good reputation is, according to Kaczyński, that a politics of history had until now been missing, with which he, of course, means a systematically Polish history politics, for it was those from the previous government—as just stated—who played carelessly into the hands of the Germans.

Poland's national conservatives admit that there is no denying that horrible crimes were committed by Poles against their Jewish neighbours. But, they believe, that should not lead to exaggerating such individual cases, to make them into an absolute, and to pillory the Polish side as a whole. As an instructive example, Kaczyński invokes the discussion about Jedwabne, because at least since the publication of “Neighbors: The Destruction of the Jewish Community in Jedwabne, Poland”, in 2000 alarm bells have been ringing in the national-conservative camp. According to Kaczyński, the historian Jan Tomasz Gross has claimed that all the Polish inhabitants of Jedwabne gathered together at the beginning of July 1941, after German troops arrived, in order to murder all the Jewish inhabitants. But, according to Kaczyński, the truth is that isolated, degenerate Poles ganged up to kill several hundred Jewish neighbours, moreover under the terms of the German occupation. So, he argues, this crime cannot be laid entirely at the feet of the Poles. Already during the fierce debate about Jedwabne that followed the publication of the book in Poland, the strong man of the national conservatives warned unequivocally: "They are trying to discredit us, to make us into Hitler’s helpers."

Poland's persistent fighters for the country's irreproachable reputation also have a recent case that—like Gross's Jedwabne book—gives them no rest. Last year, the noteworthy book entitled “Dalej jest noc” [Night without End: The Fate of Jews in Selected Counties of Occupied Poland] was presented at the Warsaw Museum of the History of Polish Jews (Polin), which focuses on research into the relationship between Christian Poles and persecuted Jews in occupied Poland. The German regime of horror remains relatively relegated to the background, whereas priority is instead given to the study of the relationships between the two large population groups in Poland. It documents the conditions and events in eight select administrative districts in occupied Poland, in which a total of 140,000 Jewish people lived in the spring of 1942 before the “Reinhardt” extermination campaign began, making up five to ten percent of the total population of individual administrative districts. In the introduction, the editors Barbara Engelking and Jan Grabowski explicitly placed the book in the tradition of Jan T. Gross, arguing that the question of the attitude of Christian Poles to the persecuted Jews after the end of the "Reinhardt" campaign should be brought more into the spotlight of scholarly investigation. In the years 1942 to 1945, according to the editors, the mindset of the Polish environment had an enormous influence on whether Jews who were able to escape the immediate extermination campaign were also able to survive the war.

It did not take long for harsh reactions from the government camp. A high-ranking representative of the Institute of National Remembrance (IPN) immediately suggested investigating whether the book even met scientific criteria. For many years, the two editors have belonged to a world-renowned research community, which in Poland, as the Polish Center for Holocaust Research, draws attention to the latest research findings with regular publications. Since 2005, thirteen extensive volumes on the murder of Jews in Europe and especially in occupied Poland have been published to date. The book presentation in the Polin Museum in spring 2018 was promptly taken by the Ministry of Culture, which is also responsible for national heritage, as an opportunity to abruptly cease future allocation of state funds to this research community. Now, when the scientists of the research community look outside Poland for new ways to compensate for the missing funds, the national-conservative newspapers immediately treat them like nest polluters and traitors to the national cause.