Picture: Sergiy Movchan

The debate on the “Ukrainian issue” has been going on for at least five years, but as of yet, no clear answer as to whether or not there is fascism in Ukraine has been found. [1] Is it merely a creation of Putin's propaganda machine, or does the “junta” really exist? The answer you get will usually depend on to whom the question is addressed. These responses can drastically vary even among people who, in theory, adhere to similar political views.

This is hardly surprising. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Ukrainian society has been finding it hard to demarcate or recognize ideological markers. Given the ongoing battles of propagandists, its political compass has by now gone completely askew. This confusion is also characteristic of civil society, which is seen to be prospering after the “Revolution of Dignity”, and which should normally be the first to sound the alarm.

Sergiy Movchan works as a journalist for Political Critique Ukraine and produced this text in cooperation with the RLS Regional Office in Kiev. Translated by Aleksandra Renoire Alekseeva

As one may have guessed, the conversation about fascism in Ukraine did not start in 2014. The tussle between nationalist and "anti-fascist" narratives had been in full swing for 10 years prior, starting during the 2004 presidential campaign. After Viktor Yushchenko’s “orange” movement was elected to government, the first wave of reconciliation and lionization of OUN-UPA [2] figures took place. Nationalist ideas, heroes, and discourses, which for some time had only been in use among members of marginalized right-wing organizations, have become fundamental to mainstream politics because of their capacity to mobilize the electorate far more efficiently than socio-economic issues would do. Soon, the counter-establishment groups from the Party of Regions [3] realized the benefits of using "anti-fascist" arguments. One of their politicians who went on to become prime minister, Mykola Azarov, even created the "Anti-Fascist Forum of Ukraine". To intimidate their East Ukrainian voters with banderivtsі (Banderites) from the country’s West, the Party of Regions secretly funded nationalists from the Svoboda organization and gave its speakers plenty of screen time on TV channels it controlled. The cooperation was beneficial for both parties. In 2012, Svoboda first entered government with a reputation for being “guys who will kick the butts of ‘those regionalists’”. The presence of the far right in mainstream politics was fully legitimized.

By 2014, there had already been many cases of far-right violence. Back then, though, the Right had to compete with anarchists and true anti-fascists for the right to control the streets. The nationalists’ successes during the violent confrontation at Maidan and their involvement in hostilities in eastern Ukraine have changed the situation dramatically. Far-right groups now hold a monopoly on street violence. This has become one of the prominent issues in the country’s political life.

How should we name these new political realities? This is a tricky question, to say the least.

Junta. Fascism. Putin.

“After the putsch of 2014 and the overthrow of legitimate power by Nazi militants for US money, the Fascist Junta came to power in Ukraine.” To put it bluntly, this sort of narrative was first promoted by Russian pro-government media immediately after the Maidan events. Through the lens of Russian propaganda, a political party such as Right Sector has grown to be the size of Marvel’s Hydra. It was reported to be responsible for all that was wrong in the world. Such discourse on “fascism in Ukraine” was even typical of top Russian officials, in particular President Putin. “Anti-fascism” came to be a convenient ideological framework that explained the essence of the Donbass war.

This explanation fits well into one of Russia’s key historical myths about the “Great Victory” over fascism in 1945 (the narrative promoted by Putin’s regime), and has led to a consolidation of Russian society. Some Western political forces also supported the "anti-fascist uprising" in Eastern Ukraine. Even today, at international conferences one may sometimes hear about “mass reprisals against the ‘people of Donbass’” and the “official ban on speaking Russian”, which has supposedly been in force since 2014.

The presence of the far right in both the Maidan militia and the national army was obvious due to the numerous photographs being regularly uploaded to social media and printed in newspapers. The inept efforts of Ukrainian government spokespersons to deny this were to the benefit of Russian propagandists. The attempt to deny the evidence has failed the people twice: for critics of Maidan it served as a justification of their views, and for Maidan’s proponents, the very idea of fascists existing in Ukraine was deemed to be both dangerous and a kind of betrayal. Mentioning “fascism in Ukraine” came to be seen as simply parroting Kremlin propaganda, radical actions by the far right were perceived as provocations arranged by the Russian security apparatus, and Putin was denoted as the only fascist (or as even worse than fascists). This pattern of interpreting fascism in Ukraine is still prevalent today.

“There Is No Fascism in Ukraine”

This phrase can be regarded as a blanket response of Ukrainian journalism to hostile positions held by the Russian media. It is the perfect narrative to circulate, both domestically and exported to a wider audience internationally. Its main thesis is a hodgepodge of lionization, silencing, whitewashing, whataboutism, and conspiracy theories (ingredients mixed in different proportions depending on the context).

Ukrainian media outlets [4] were sincerely committed to fighting for the country’s interests on the media front, therefore they simply refused to see neo-Nazi symbols on the standards of volunteer battalions, or to recognize swastikas on clothing beloved by the Ukrainian patriots’ Svastone brand, or to pick out anti-Semitic lyrics from the bands performing gigs for veterans. Every media article where nationalists were portrayed in a negative light was counteracted by an enthusiastic rebuttal from the local community of journalists.

When the US Congress announced plans to include the Azov Battalion in its list of terrorist organizations in late 2019, they were met with vigorous pushback from Ukrainian experts, politicians, and officials, who opted against objectively considering the evidence outlined by the congressmen because it could potentially harm the “image of the country”. Bellingcat, a group of international investigators, was also affected by this. During the period when the group was investigating Russia’s involvement in the shooting down of Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 that had flown through Donbass airspace in 2014, it was well-cited by Ukrainian media. But immediately after the group started to focus on Ukrainian far-right activities and published a text about what was definitely an occupation of the Ministry of Veterans Affairs by nationalists, the “Russian trace” was “found” among the Bellingcat activists themselves. The Russian element was “tracked down” by a former head of the ministry, Irina Fries, who is now a deputy from the European Solidarity Party. She said the group was “infiltrated by people from the Federal Security Service of Russia”.

Members of Ukrainian civil society do not have a problem with the attacks of the ultra-right on the “politically wrong” journalists either. For example, in the report by ZMINA Centre for Human Rights, the physical attacks on journalists working for the opposition 112 TV channel and for the Shariy.net and Strana.ua websites, or indeed the rocket-propelled grenade attack on the channel 112 building were not mentioned. In the media community, there is no tradition of expressing solidarity with journalists from opposition channels, or even of recognizing them as journalists.

Media experts took part in active denial of the fascists’ existence in Ukraine. Founded in 2014 and designed to combat the lies of “Kremlin propaganda in all its aspects and manifestations”, the StopFake website has been actively engaged in “exposing fake news” about fascism and Nazism in Ukraine. "StopFake has repeatedly pointed out that ‘fascist Ukraine’ is one of Russian propaganda’s favourite topics. According to these “media experts”, there have been no reliable facts, either now or in the past, to back up the bold statements about the “return of fascism” to Ukraine.

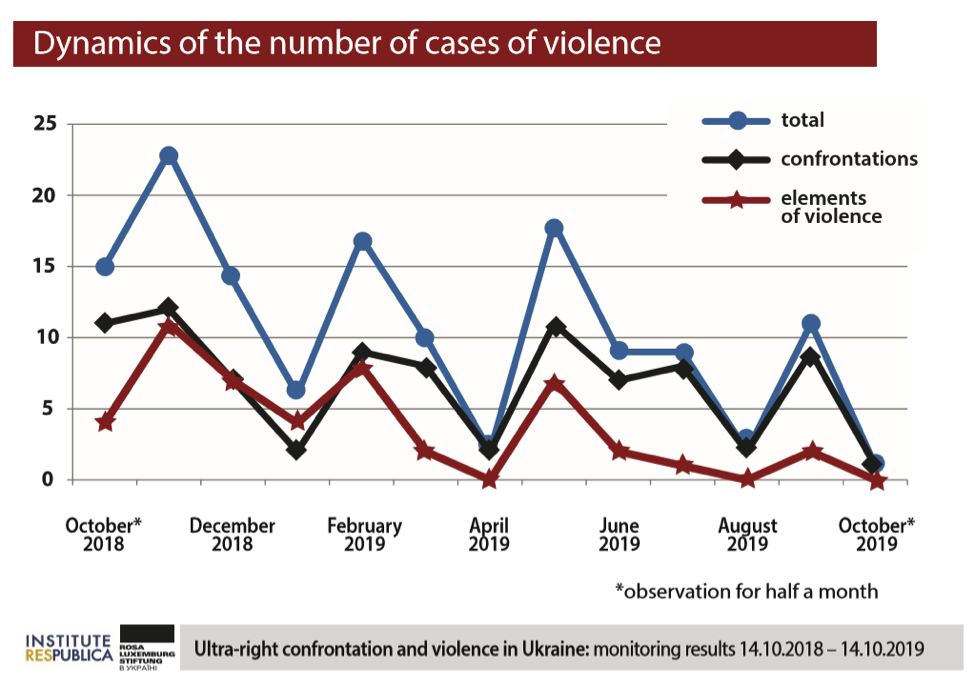

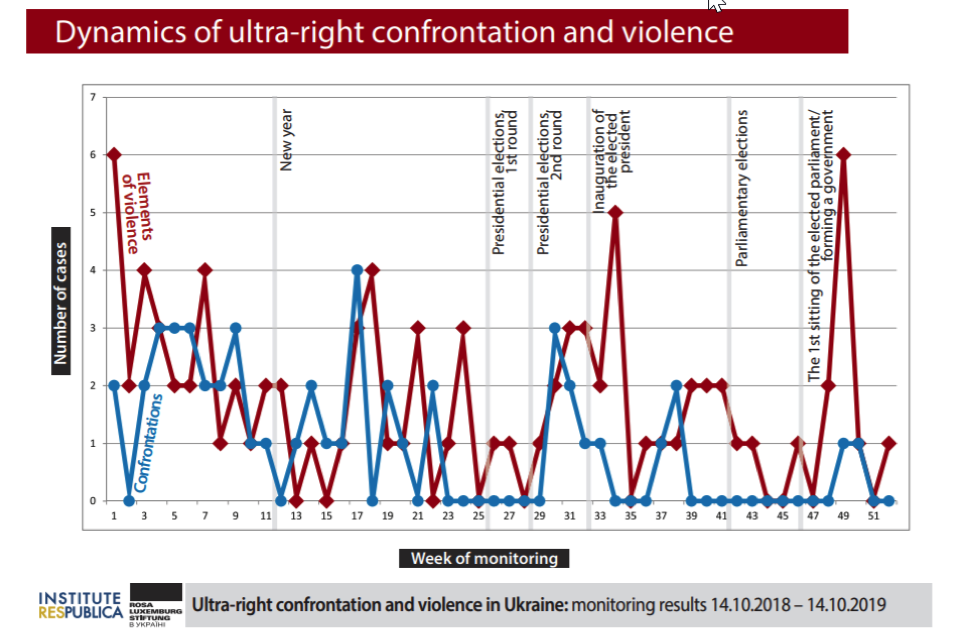

Even more important is the blindness of much of civil society to street violence, despite the fact that it should be almost impossible to ignore. The team was monitoring far-right violence from 14 October 2018 to 14 October 2019, and recorded 137 cases, 89 of which were violent. Attacks on political opponents, left-wing activists, art exhibitions, journalists, feminists, representatives of the LGBTQ community, and ethnic and religious minorities have become commonplace in the last five years. Nevertheless, media outlets prefer to see the perpetrators of such attacks as some sort of “Kremlin provocateurs” who “paint a colourful picture for Russian television”, or instead they are called “activists and patriots”. This is especially true if the victims of such attacks lack significant public support due to political circumstances or public prejudice.

The series of attacks on Roma communities that swept through Ukrainian cities in 2018 is quite illustrative. The burning down of the temporary settlement of Roma in Kiev’s Holosiivskyi Park and the immense positive media boost it gave the far-right C14 organization [5] have demonstrated to other far-right groups a “recipe for success”. The attackers continued to appear on television and give interviews up until the most recent incident of racist violence in July 2018, when an attack on a settlement near Lviv resulted in one dead and several others left with stab wounds (a 10-year-old child among them). After the murder, the situation has somewhat changed. The Lviv attackers were arrested and the attacks stopped. [6]

The same tactics are being used by the ultra-right in attacks on left-wing activists, LGBTQ pride parades, trans marches, and feminist rallies. For the media, such attacks are touted as a conflict between outraged patriots on one side and anti-Ukrainian forces, or “perverts” on the other, and the media has eagerly promoted this point of view on the matter.

It works the other way around, too. Public anti-Semitic statements, not to mention physical attacks rooted in anti-Semitism, are mostly condemned in society. The reputational risks from such actions are also understood by right-wing radicals, so blatant anti-Semitism has been excluded from their PR strategy. Ukrainian human rights activists, therefore, felt legitimized to state that the attacks on Jews had virtually ceased,[7] and street-level anti-Semitism, as a phenomenon, had virtually disappeared after the Euromaidan

New Human Rights Defenders

Immediately after the Maidan events, the public sector in Ukraine exploded in size. Numerous initiatives have tried to promote change in the state. However, mentioning the problem of far-right violence perpetrated by combatants in the war and by those who had been allies at the barricades was somewhat unpatriotic. Nationalists, even if they committed crimes, could count on legal advice and support. After a while, members of far-right groups even joined the human rights movement which ceased to regard them as foreign to its interests.

One of the latest, and most resonant assassinations—of Kherson activist Kateryna Gandzyuk in autumn 2018—became an important topic during the presidential race. And although the murder was committed by youths with a far-right background, various far-right organizations later joined the campaign to protect civic activists. “Surprisingly”, victims of violent acts of C14, National Corps, and other nationalist organizations were not included in the list of persecuted people. All of the reminders that this should be carried out were rejected. At the event commemorating Gandzyuk (where members of the far right were present), representatives from liberal NGOs tried to prevent such victims from taking part—to “avoid provocation”.

Sergiy Sternenko, a well-known Odessa Right Sector activist, joined the campaign against the persecution of activists as well. It would seem that due to his criminal history (among other cases, he stabbed one person, he claims in self-defence, during an alleged attack by two men), we might expect him to be awaiting the court decision in a pre-trial detention centre. But thanks to the “magical” power given to this “activist” and “patriot”, the murder suspect became a victim, and would go on to become a prominent public figure who gives speeches at human rights discussions,[9] and regularly meets with well-known public figures and leaders within society.

The ranks of Ukrainian civil society were “replenished” with members of Honor, a far-right chapter of football hooligans. They have been recorded as attacking black fans, some are known to be activists within the Azov Civilian Corps, and they have also demanded investigations into the murder of Gandzyuk, gone to protests in Hong Kong and Paris, and like Sternenko enjoy the full support of the Ukrainian human rights sector.

C14 members are gradually finding their place in the (human rights) sun. As the right-leaning journalist Valeria Burlakova reports, the aforementioned Ministry of Veterans Affairs has set up a working group to monitor the rights and freedoms of veterans convicted of crimes or taken into custody. The group includes the following: Denis Polishchuk and Andriy Medvedko—both key suspects in the murder of writer Oles Buzina—as well as another member of the C14, Alexander Voitko, who is the coordinator of the Union of Veterans of the War with Russia. Even before that, C14 leader Yevhen Karas became a member of the National Public Control Council’s Anti-Corruption Board through questionable online voting, and Polishchuk heads the C14-affiliated National Centre for Human Rights.

For their part, representatives of far-right groups have also put in a lot of effort: they have meticulously learned the specifics of the “third sector” language. Now we can hear from them about “far-left terror”, the sexist conduct of “foreigners” towards Ukrainian women, or about the “racism” of Roma human rights activists. “We are not racists! We don’t care what colour those who violate the rights of Ukrainians are, black or yellow”, said Yevgen Strokan, a member of the Unknown Patriot, when his gang disrupted the press conference commemorating the attacks on the Roma community.

Politically “Marginalized”

Of course, the world is not black and white, and it is impossible to reduce the issue of right-wing radicalism to the question of “who is a real fascist, Poroshenko or Putin”. From a certain point in time, many experts have begun to turn their attention to the activities of far-right organizations in Ukraine. Freedom House mentioned the far-right attacks in its 2018 annual report. However, some experts were reluctant to “repeat Russian propaganda”, preferring to distinguish between “ours” versus “theirs” based on the criterion of the attitude to “the Ukrainian issue”.

The main point of divergence here is the extent and origin of far-right activism, not the question of “whether there is fascism in Ukraine” (the answer is obviously yes). In the wake of Russia talking about the “fascist junta”, they felt pressure to reassure their Western partners that the scale of far-right extremism was clearly exaggerated and that these were the deeds of political outsiders, on the margins, unable to influence public policy. And they have somewhat succeeded in proving this—as electoral data would indicate.

Indeed, even during its strongest period, in the 2012 elections Svoboda received a modest 10 percent of the vote. And in the 2019 parliamentary elections, nationalists united and formed a coalition which received only 2.15 percent of the vote. For the most part, their candidates failed to be elected.[9] In comparison to European countries where the local far-right parties are well represented in parliament, or even formed part of a governing coalition as in Austria, it might seem like far-right political prospects in Ukraine are bleak. There are, however, some fundamental differences.

Firstly, Ukrainian politics has never been based on ideology. It is no secret that virtually since the moment of independence (or at least since the beginning of Kuchma’s presidency in 1994), the struggle for power between financial and industrial groups has been ongoing in Ukraine. They use ideological messages only as a means of legitimizing their own existence and mobilizing the electorate. Politicians’ reputations and the circumstances of the moment carry more weight than policy statements. To illustrate this point, in the recent parliamentary elections, voters cast their ballots for people both unknown to them and completely lacking in political experience, just because they represented the pro-presidential party “Servant of the People”. Therefore, the perspectives of right-wing parties are indeed somewhat invisible within parliament. They are, however, just as invisible as any other political force rooted in ideology (e.g. liberals) unless such a force joins a broader coalition containing eminent politicians. But does this result in a fundamental inability for the far right to get into parliament, or even to form part of a victorious coalition? Of course not!

What gives power to the far right and allows them to influence public policy (sometimes even more effectively than parliamentary factions) without being represented in parliament is their level of integration into the civil service and military and law enforcement agencies, their access to weapons, their having built up infrastructure over many years, access to sources of funding (including from state and city budgets), total street-level control, and the hegemony of nationalist discourse in a country that legitimizes their violent actions. It is rare that a Western European country could boast of such riches belonging to a “marginalized” far right. Is that why Ukraine has become a tourist mecca for Nazis from all over the world?

The fact that ultra-right violence is not a one-off event can be indirectly shown by statistics. After all, during the period 2018–19, the number of attacks can be seen to peak when important political events take place, such as presidential or parliamentary elections. They fall sharply immediately after.

Another way to diminish the ultra-right’s weight in society is to deprive them of their agency. The media and NGOs claim that the far right borrowed their ideas straight from Russia, or that they comply with Russian State Security Service orders. From a rhetorical point of view, this discursive strategy makes sense (who in Ukraine would even love Russia?). However, even before Maidan, the far right actively cooperated with both the Russian far-right movement and with like-minded Europeans: the Jobbik and Fidesz parties in Hungary, Marine Le Pen’s Front National, and others. But despite the obvious ideological intersections, most ideas of the Ukrainian far right originate in the classics of European conservatism, and consist of either international white racism or Ukrainian nationalism.

As to whether there is direct collaboration with the Russian Federal Secret Services (FSB), there are indeed several cases where such links could be found. For example, there is the case of Polish neo-Nazis who set a Hungarian cultural centre in Uzhhorod on fire in February 2018, or the situation with former UNA-UNSO [10] breakaway chairman Edward Kovalenko, who was given back to Russia during the last prisoner of war exchange. In 2004, Kovalenko organized a march in support of Viktor Yushchenko, in which Nazi regalia could be seen and he made provocative xenophobic statements. [11] It is quite telling that journalists do not shy away from using words such as “fascism” or “neo-Nazism” in writing about them. But such cases seem relatively minor when shown against the backdrop of more than a hundred confrontational or violent actions committed by Ukrainian far-right parties over the course of a year. The evidence of the “Russian trace” is mostly reduced to the existence of Russian-speaking members among them (the presence of large numbers of Russian-speakers among nationalists is a well-known fact) or to grammatical misspellings in Ukrainian neo-Nazi graffiti (this, reportedly, indicates the FSB’s hand in the matter, rather than the level of education of “activists”).

…Über Alles!

It is unfortunate, but the responsibility for the success of the far right lies largely with representatives of civil society. Every time when people are outraged by another attack or act of vandalism, well-known public intellectuals boldly ask: “Who are these swastika monsters who painted the Sholem Aleichem monument?” “Who has beaten these guys and girls marching in the Kharkiv Pride?” And they find a universal answer: “Kremlin agents”.

This creates a paradoxical situation in Ukraine: the same people simultaneously defend human rights and legitimize those who regularly violate human rights. All the same experts and opinion leaders on the one hand strongly support the promotion of gender equality in society and the pursuit of LGBTQ pride, and on the other hand engage in patriotic activities with those who attack LBGTQ pride. They join the attackers in the anti-capitulation marches or demand to investigate the crimes against civic activists.

The slogan “Human Rights above all” (ponad use in Ukrainian), which is quite popular at human rights rallies, is an attempt to redefine the nationalist slogan “Ukraine above all” in a liberal way. But now it has returned to its original meaning. When it comes to nationalists, veterans, volunteers, or simply “pro-Ukrainian activists”, it is not human rights they are asking for, instead they are most concerned with ethno-nationalist discourse and those who fight for the “Ukrainian order”.

But the situation could be changed. If we want the far right to lose legitimacy, the first step could be for the representatives of Ukrainian civil society to refuse to cooperate with them. This would allow civil activists to objectively investigate the human rights violations and to reduce the risk of street attacks. If they only were to officially recognize the problem of fascism in Ukraine, even if still minimizing its prevalence, it would nevertheless be a positive step, because it would harm the Russian propaganda narrative. It would also have the potential to significantly improve Ukraine’s image in the world, turning it from the country where neo-Nazis come for their pilgrimage to a country that is struggling with this shameful phenomenon.

[1] The issue of terminology is often the cornerst one of discussions about right-wing radicalism in Ukraine. In extreme cases, it all boils down to the formula “fascism was in Italy. Learn history.” The author is aware that there are significant differences between the various radical-right ideologies, and that some representatives of the nationalist movement may condemn fascism and Nazism and oppose violent methods. But the very term “nationalist” has become a popular means of self-identification for almost all right-wing organizations in Ukraine, be they truly nationalist or overtly neo-Nazi. And in the ranks of initially nationalist organizations there may be a large number of radicals whose activities are in no way condemned. Given this, we felt it legitimate to use the words “nationalists”, “right”, and “far-right” as interchangeable. The word “fascism” is also used as a general framework to refer to the various ideological trends of right-wing radicalism: fascism, Nazism, neo-Nazism and other discriminatory ideologies, excluding more traditional nationalist organizations.

[2] The Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists - Ukrainian Insurgent [Povstanska] Army (OUN-UPA) is a nationalist organization (OUN) that later formed the military organization of Ukrainian nationalists (UPA) and operated before, during, and after World War II, mainly in the lands of Galicia and Volhynia. In the Ukrainian national-patriotic discourse these are considered to be heroes who fought for independence against the Polish, German, and Soviet forces. In Soviet times, they were deemed to be collaborators with Nazi Germany.

[3] In September 2009, the then-Prime Minister Mykola Azarov created the Anti-Fascist Forum of Ukraine.

[4] According to a poll conducted by the Democratic Initiatives Fund in June 2019, 96 percent of journalists reported that there was censorship in the Ukrainian media. 23 percent felt it was necessary, and 26 percent were convinced that a number of topics should not be raised in the media. Among the topics not to be mentioned are: bad sides to the Ukrainian military, such as alcoholism, drug addiction, and looting among volunteers in Donbass; life in the occupied territories; the situation in the army; the Euromaidan events; the 2 May 2014 tragedy in Odessa; and texts depicting Russia in a positive light. The main enforcers of censorship are, according to journalists: owners of media organizations (according to 94 percent of respondents) and self-censoring journalists (48 percent).

[5] In 2019, the court upheld a C14 lawsuit against Hromadske. The TV channel was defending its right to call the group “neo-Nazi”. The court forced the media to publicly retract this term in reference to C14. Hromadske plans to appeal the decision in the Supreme Court. On 28 September 2019, C14 representatives announced the transformation of the organization into a political party, the Society of the Future.

[6] Here we refer to the attacks on Roma settlements. Despite the pogroms having ended, the Kiev City Guards organization, composed of C14 activists among others, continues to document its fight against Roma living close to the Kiev railway station. The press conference on the commemoration of the first attack was thwarted by representatives of the far-right group Unknown Patriot.

[7]The assessment of the level of anti-Semitism in Ukraine by different organizations varies greatly. The United Jewish Community of Ukraine (UJCU) report identifies 107 (90 direct) incidents of anti-Semitism in 2018. This data directly contradicts the Vaad Ukraine report. Those authors criticize the UJCU methodology and conclude that “in 2018, no cases of anti-Semitic violence were reported in Ukraine. Just like in 2017”, and that there is frankly no such thing in Ukraine. The UJCU report lists 66 cases of anti-Semitism for 2019 while Vaad reports only 10 (as of October 2019).

[8] The following people took part in the discussion with Sternenko: Lyudmyla Denisova (the human rights commissioner), Oleksandr Pavlichenko (the Executive Director of the Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union, or UHHRU), Matthew Shaaf (the Director of Freedom House in Ukraine), and other representatives of leading human rights organizations.

[9] One deputy from the Svoboda party, Oksana Savchuk, managed to get elected to parliament in the single-mandate district of Ivano-Frankivsk. Also, some nationalists could be found in the party list of Petro Poroshenko’s European Solidarity Party.

[10] The Ukrainian National Assembly – Ukrainian People’s Self-Defence (UNA-UNSO) is one of the most prominent nationalist organizations in Ukraine. Its activity peaked in the 90s. Members of the UNA-UNSO participated in the wars in Transnistria, Georgia, and Chechnya. There was a split in the organization following mass arrests of its members after they participated in radical anti-presidential protests in 2001.

[11] At the same time, the previous UNA-UNSO chairman, and now the leader of the Brotherhood (Bratstvo) organization, Dmytro Korchynsky, had joined the campaign to discredit Viktor Yushchenko and actively cooperated with openly reactionary pro-Russian forces: the “Progressive Socialists” led by Nataliya Vitrenko, and Alexandr Dugin’s Eurasian Youth Union. In 2013 the orientation of Brotherhood activities changed and they turned into prominent Ukrainian patriots and fighters against Russian aggression.