Climate activism has risen to the forefront of the global conversation in the last few years, with activists like Greta Thunberg and the FridaysForFuture mobilizations she inspired fundamentally shifting how global warming is talked and thought about in the public sphere. In the US and UK, demands for a “Green New Deal” dominate progressive political discourse, while in the European Union even conservatives are getting on board, with EU Commission President Ursula van der Leyen promising to deliver an infrastructural “Green Deal” to the continent in the years to come. We are still a long way from the kind of paradigm shift we would need to mitigate the catastrophic impacts of climate change, but the pace of change in the discourse is nevertheless remarkable.

But what about the Global South? For the most part, conversations around climate change remain dominated by voices from Europe and North America. Chinese pledges to reduce emissions sometimes make headlines, but the situation facing the hundreds of millions of people living in Africa—one of the regions that threatens to lose the most as the world heats up—remains conspicuously absent.

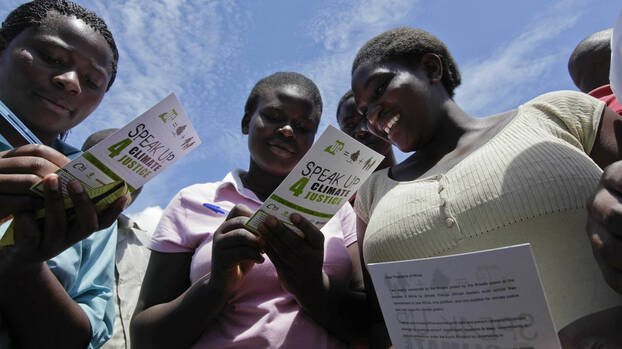

This is unfortunate and counterproductive, as Africa is home to many vibrant mobilizations for climate action and social justice that too often go unheard on the stage of global public opinion. Franza Drechsel spoke with Roland Ngam, a climate activist and programme manager at the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung’s Southern Africa Office, to learn more about the struggle for climate justice in Africa and his new project, ClimateJusticeCentral.

FD: The German media gives the impression that the climate crisis has severe effects on African countries, but that neither the governments nor the people of Africa are particularly concerned about climate policy. Does the climate crisis not mobilize activism on the African continent?

RN: This perception is erroneous. Since most African countries are mostly agrarian, the continent is intimately aware of climate change due to the effects people experience on a daily basis.

Then what kind of social movements exist?

There are plenty, mostly not self-identifying as “climate justice movements”, such as trade unions and community organizations fighting against mining or the effects of the encroaching oceans. More concretely, in Southern Africa there is a strong landless people’s movement with one million members.

Roland Ngam works as a Programme Manager of Climate Justice at the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung’s Office in Johannesburg, where he coordinates the climate blog ClimateJusticeCentral.

Franza Drechsel works as a Project Manager and Advisor for West Africa at the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung in Berlin. This interview originally appeared in maldekstra #10.

What is the link to climate justice?

Where agriculture is the main source of income, as in most African countries, land is essential for survival. People lose their subsistence due to droughts, changes in rainfall, coastal erosion, or other climate effects. They might also lose it due to land grabs as well as pollution from agribusiness and mining companies. Or they lack access because of the unequal land distribution which has persisted since colonialism.

It sounds like the biggest climate justice movements are located in rural areas.

That’s right. Encroaching oceans in Mauritius or Senegal, desertification in Burkina or Nigeria, industrial mining in South Africa or Morocco—all this mostly affects rural populations, often the poorest of the poor, who organize with little help from outside.

Are there no links with urban movements?

There are very few sustained mass urban-rural movements. In Cameroon, we have seen strong impromptu collaboration between urban and rural populations recently, which forced the government to revoke the forest exploitation rights it had granted to international logging companies. Similarly, after the oil spill in Mauritius in July 2020, the Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung’s partner organization CARES was quick to mobilize the biggest protest action in the country’s modern history with 100,000 people.

Are the few urban-based movements then the reason why Western media do not report on activism?

Yes. One reason is that the active populations are fairly rural. Secondly, unusual actors such as the Catholic Church are very relevant in some places. Thirdly, agitation has to happen differently than in democratic societies, as governments repress all sorts of power-contesting movements, and environmental mobilisations are perceived as precisely this: a challenge to governments.

Can you give an example?

When the Ogoni people in Nigeria started to fight for justice and resist oil pollution by Royal Dutch Shell and British Petroleum in the Niger Delta in 1970, the Nigerian government reacted very harshly. Public servants, government officials, and military personnel have close ties to the staff of the oil companies, since oil means money. Therefore, any movement that threatens these networks and informal agreements is resolutely repressed. The peak of state reaction was in 1995, when nine activists from the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People were executed after an unjust trial.

Can state repression also lead to growing support for movements?

I am an optimist. Hence, I would say that, in the long run, activism leads to the election of local parliamentarians and civil society expanding its power bit by bit, as is the case in the Niger Delta. There are mass movements based around climate issues, too.

What do you mean?

One example is the government under Thomas Sankara, which mobilized to plant more than one million trees in Burkina Faso as a way to prevent desertification following the severe Sahelian droughts, which occurred between 1965 and 1974 and lasted all the way into the mid-1980s. Other presidents followed. The idea of a “Great Green Wall” along the Sahara was taken up again in 2001, supported by many African political institutions. Unfortunately, nothing much has happened since because the political class has not involved the wider citizenry or private sector in the project.

How do you see the relationship between climate justice movements in Africa and in the Global North?

There is room for improvement, I would say. So far, African priorities such as drought, desertification, mining, malaria, disappearing rainforests, etc. have not yet played a key role. Concepts like the Green New Deal do not refer to them.

Are there examples of fruitful collaboration?

The Pacific Island Nations were only successful in making states sign the Paris Agreement because they built partnerships with Europe and the Americas. Similarly, many of the rural movements in African countries would not have been successful if they hadn’t cooperated with groups from the Global North. Again, I take the example of the Ogoni: only because they partnered with pro bono lawyers and CSOs in the Global North were they capable of winning a recent court case against Royal Dutch Shell. Collaboration is necessary—for governments as well as for movements.

You coordinate ClimateJusticeCentral, a new blog covering climate issues with a distinctly African focus. Could you outline why such a project is necessary?

This brings us back to the start of our conversation. Far too little is published on the raw daily impacts of the climate crisis. ClimateJusticeCentral not only portrays these, but also features the voices of people from across the Global South. I hope that the blog contributes to a better understanding of the climate crisis and that it will lead to more collaboration to increasing steps for climate justice.