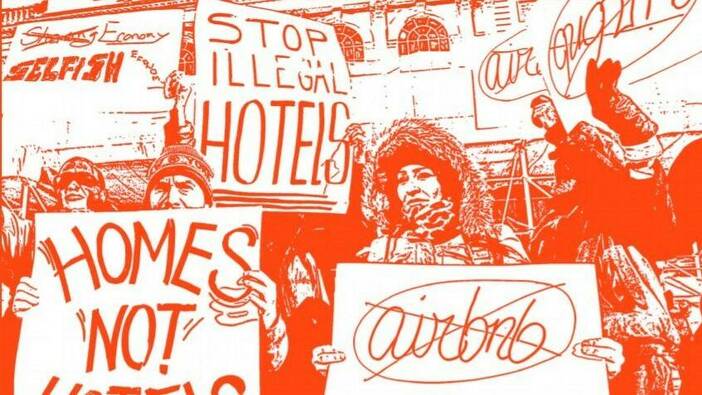

This report is about citizen participation that is funded and coordinated by businesses. The case study is Airbnb, one of the biggest companies in the “platform economy”, which resources and mobilizes its landlords to lobby for its preferred forms of regulation. Since 2008, numbers of short-term rentals, many of which might otherwise house permanent residents, have expanded dramatically all over the world. Problems around housing shortages, tourism, taxation, and urban conviviality have led to social movement opposition and local attempts to regulate in San Francisco, New York, Berlin, Barcelona, Paris, and dozens of other cities worldwide.[1]

Luke Yates is a Lecturer in Sociology at the University of Manchester whose research focuses on collective action and socio-economic change. He is currently working on political struggles around the platform economy, corporate-funded civil society initiatives, and social movements’ conceptions of “everyday politics” and “strategies”.

Since 2014, a key part of Airbnb’s political response has been the use of grassroots lobbying, a phenomenon where businesses influence societies by creating apparently independent social movements to act on their behalf. Airbnb presents carefully curated and intensively coordinated groups of landlords who have a single room or property as “people power”, an Airbnb “community” or “movement”. This offers the company legitimacy and additional political influence to protect a business model that is increasingly dominated by professional accommodation providers, not “home-sharers”.

Platform-sponsored grassroots lobbying is a public form of corporate lobbying, yet little is known about it and there is generally no regulation of the practices involved. It is becoming widely used across the new digital “platform” economy, including ride-hailing companies such as Uber and Lyft, to delivery companies such as Doordash, to electric scooter companies GetAround, Lime, Scoot, Spin, Bird and Lyft Scooters. Grassroots lobbying is now a key tactic for disruptive new businesses facing regulation, but its current scale, how it works, and its social and political impacts have received little attention.

The claims posed here are based on the first in-depth investigation of platform-sponsored grassroots lobbying. [1] In this work, we analysed documents and interviews with twenty-one former Airbnb public policy staff who worked across fourteen countries in North America and Europe, including Germany, Austria, and the UK. The report focuses on the campaigning practices of the groups Airbnb creates and coordinates that it calls “host clubs” or “home sharing clubs”.

Home sharing clubs are associations of selected Airbnb landlords who are resourced, mobilized, and coordinated by Airbnb public policy teams to advocate for favourable regulation. These associations are made up of an unrepresentative segment of Airbnb landlords—mainly those that share their own homes or rent them short-term. They are created predominately and in disproportionate numbers in cities where the effects of Airbnb are leading to calls for stricter regulation. Like more traditional lobbying and PR practices, they target public officials and public opinion. They have been deployed in hundreds of towns and cities globally, through the hiring of hundreds of “community organizers” whose main role is to create host campaigns that are politically useful to the company. The Airbnb case is still the most intensive and sustained platform-sponsored grassroots lobbying strategy in the world to date.

This report provides evidence of how digital platforms are governed through the case study of Airbnb’s home sharing clubs. It is divided into six parts:

- First, an introduction to the debates and struggles that circulate around the sharing economy and short-term rentals, the context for Airbnb’s grassroots lobbying campaigns.

- Second, a description of the home sharing club model. This part highlights the purposes, aims, and main practices of host clubs.

- Third, an explanation of who participates in corporate campaigns and how participants are recruited.

- Fourth, a review of the various forms of support offered by the company to participants in Airbnb campaigns.

- Fifth, a discussion of the implications of platform-sponsored grassroots lobbying, drawing on interviewees’ anxieties highlighting reflections and critiques from former staff.

- Sixth, an exploration of the influence of Airbnb on the wider practices of platform-sponsored grassroots lobbying with Uber, Lyft, e-scooter companies and vaping giant Juul, and a consideration of the future of corporate grassroots lobbying.

These sections also correspond to some central claims that were made by Airbnb in their public-facing materials about their home sharing clubs: 1) that fighting against regulation is only one of their many purposes; 2) that clubs are “independent” of the corporation; 3) that clubs are made up of a diverse constituency of stakeholders of landlords, guests, small business owners, and local civil society leaders; and 4) that their impact is chiefly the empowerment of ordinary people and the education of society and law-makers.[3] The report finishes by drawing out some recommendations for how government, civil society, and business might deal with platform-sponsored grassroots lobbying and in particular the case of Airbnb.

The “Sharing Economy” Discourse: Promise and Disappointment

“I’d define the sharing economy as a way for companies to offload costs and risks associated with training, developing, creating products to ‘entrepreneurs’ so that they can maximize the level of profit.” (Brianna, West Coast US)

“It’s no more a home share than somebody who owns a boutique hotel or a bed & breakfast.” (Sam, West Coast US)

Airbnb, like the “Sharing” or “Collaborative Economy”, was initially promoted for its potential to create new sources of income, employment, strengthen community, and save resources. By 2016, the European Commission had declared the collaborative economy to hold “significant potential to contribute to competitiveness and growth … to promote new employment opportunities, flexible working arrangements and new sources of income”.[4] But it is now widely recognized that these benefits are not materializing.

In the case of Airbnb, business has grown rapidly, with tens of thousands of listings in many cities. This appears to affect availability of housing for permanent residents, contributing towards gentrification. The majority (59 percent) of Airbnb listings have become “professional accommodation offers”, only 8 percent of listings are one room of a single home.[5] High availability throughout the year for many listings removes them from the residential market.[6] An industry of property management companies now allows landlords to play little role in “hosting”.

Above are quotations from former community organizers, staff who are employed to create and coordinate host clubs. Airbnb continues to actively propagate the Sharing Economy discourse, but even the former Airbnb staff interviewed tended to see it as marketing spin that was hiding the problems in the sector.

Airbnb’s public narratives continue to highlight a minority of cases on the platform, misleadingly suggesting they are representative of the business. The ‘sharing’ and ‘collaborative economy’ is now widely regarded as a misleading concept—the only actors promoting it now are companies such as Airbnb.

What Are Home Sharing Clubs For? Airbnb’s Response to Regulatory Pressure

“I was an organizer, so my aim was to turn out people for this campaign that we were working on.” (Kate, West Coast US)

In contrast to the early campaigns where Airbnb boasted openly about their political successes, the most recent public facing materials available downplayed their political function. Airbnb’s FAQ page for home sharing clubs, for example, mentioned this as the second among five other purposes:

Home Sharing Clubs are independent, host-led local organizations that drive initiatives to better their neighbourhoods. Clubs advocate for fair and clear home sharing regulations in their city, share best practices around hosting and hospitality, organize community service activities, and can serve as a forum to connect those who share a passion for home sharing.[7]

In some other pages and “news items” for home sharing clubs, and strikingly in their S-1 report released prior to the company going public, the political aim of the clubs is not mentioned at all.

Airbnb’s mobilization tactics and the home sharing club originated in heavily resourced key regulatory struggles in San Francisco, Barcelona, and New York. The clubs are associations of selected Airbnb landlords that are resourced, mobilized, and coordinated to advocate for favourable regulation. Since then, the number of clubs has grown to 350–400 globally, 40 percent of which are outside of the US, and they have employed hundreds of community organizers.[8]

Interviews with former staff, job descriptions, and public speeches from key Airbnb staff show that clubs and their paid organizers are evaluated in terms of their success in building campaigns and mobilizing users for favourable regulation. Clubs hold meetings, attend and give evidence in legislative hearings, lobby officials by phone-banking, letter-writing, in-person or by open petitions, liaise with media, and convene protests.

Public-facing materials from the company downplay their political function despite extensive evidence that this has been their main purpose.

Who Joins Airbnb’s Home Sharing Clubs? Recruitment, Selection, and Exclusion

Did you recruit people with more than one listing?

“My mission was actually to keep them away.” (Cassandra, Southern Europe)

“I mean not really just because they’re the whole reason why the city wants to legislate and by that person buying up a bunch of properties, especially maybe in low income neighbourhoods where the housing is necessary… I felt uncomfortable with them there.” (Frankie, Latin America)

“So I guess that meant if you did find people who didn’t fit that profile you wouldn’t follow up with them.” (Kati, Central Europe)

Participation in Airbnb’s political campaigns and composition of home sharing clubs is carefully curated.

Professional landlords on the platform, the most controversial, and accounting for a majority of listings, are excluded. This is apparently done in order to present a benign impression of the company.

After an extensive search for appropriate recruits, Airbnb staff hold an intensive series of meetings and meet-ups with those who have “good stories”, building trust and increasing their “asks”, which become increasingly political and involve increasing responsibility. Specific landlords’ personal biographies or curated “stories” are subsequently used in marketing and for court hearings and campaigns to lobby key decision makers.

These findings contrast with Airbnb’s public account of the composition of Airbnb’s campaigns, which suggests that they are made up of an organic and highly diverse “community” movement of Airbnb stakeholders.

How Is Airbnb Affiliated with Home Sharing Clubs?

You talked a bit about the training of the people who would give their stories. What preparation was involved for the court hearing?

“We had a run through [rehearsal]. We had other teams actually fly in to come and help us, because we would have done the same thing if any other legislation had come up in their cities as well. We had the people who were speaking, just making sure their stories were in order … We had a run of show.” (Participant fully anonymized for confidentiality).

And did you have to charter your own buses [to attend the state capital to protest] or was it just getting people on to Greyhounds, or something?

“Chartered our own buses. They tried to make it as convenient as possible, because it’s easy for people to be like, ‘Yes, I’ll get involved’, and then they find out that they’ve got to spend $12 on the bus. They’re like, ‘No’. So we have to make sure we pay for that for them.” (Taylor, East Coast US)

“We made some signs actually, as a team, just to give out to people that wanted to hold them.” (Anthony, Mid-West US)

The support, resources, and influence offered by Airbnb to home sharing clubs is extensive. Airbnb former staff describe many forms of support and influence, including protesting alongside landlords, organizing many aspects of protests, political education and training, editing and rehearsing of curated “stories”, and suggesting policy that the company wanted.

There are examples of clubs disagreeing with Airbnb or highlighting the problem of business hosts, suggesting that sometimes campaigns did demonstrate independence. Yet these examples are presented as failures of the public policy team. The aims of clubs and the aim that they are “independent” are contradictory priorities which staff struggle to negotiate.

Airbnb, contrary to this evidence, continue to claim that its home sharing clubs are independent of the company.[9]

What Are the Effects of Airbnb’s Home Sharing Clubs and Grassroots Lobbying?

“Well of course we were successful!” (Kate)

How did politicians and the public treat these campaigns? Do you think they mistake them for organic campaigns?

“I absolutely think so.” (Manny, UK and Ireland)

“I think there is a lot of power that users of platforms have if they organise together, and if they demand certain things [of the client company].”

OK, were there examples of things that they did achieve in that role?

“I don’t think so, actually.” (Sarah, Central Europe)

Some interviewees think that grassroots lobbying is an improvement on standard lobbying, or is justified by the benign nature of the selected landlords supported. Some former staff consider the tactic positive because it empowered and educated landlords and increased participation in absolute terms in certain public political processes.

Yet many former employees also see Airbnb’s grassroots lobbying strategy as problematic because the ethos of community organizing is at odds with the company’s corporate goals. There are also concerns about insufficient public transparency about the support offered by the company; and fears that Airbnb’s tactics give them further unfair political advantages over local citizen campaigns and governments.

Former Airbnb employees voice a range of views and some significant concerns about the implications of home sharing clubs.

The Airbnb Model? Current Practices and Future Prospects of Corporate Grassroots Lobbying

“Who knows, maybe in three or four years you’re going to have people protesting GDPR and it turns out that it’s Amazon astroturfing or Google astroturfing. … Anybody that needs favourable regulation and has enough money to hire organizers, I think in the next five to ten years they’ll start doing that.” (Taylor, East Coast US)

Subsequent career paths of some former members of its mobilization teams suggested strong demand for their experiences and skills in other businesses, including Uber, Lyft, Doordash, GetAround, Lime, Scoot, Spin, Bird and Lyft Scooters, and JUUL, the world’s biggest vaping company (albeit not a platform), which has recently also faced regulatory challenges. This suggests further potential growth in the practices developed in Airbnb. Corporate grassroots lobbying practices involve a range of different techniques from short-term “user mobilization” to “front groups” and “curated stories”, many of which have commonalities with strategies by tobacco companies or fossil fuel companies funding climate change denial.[10] There is evidence to suggest that platform economy businesses have innovated around existing corporate political organizing techniques and are rejuvenating and inspiring corporate “grassroots” campaigns elsewhere.

One senior lobbyist and former Airbnb public policy head said that corporate-funded citizen lobbying was increasingly recognized by professionals as more effective and, he argued, as having greater legitimacy, than traditional closed-door lobbying. While grassroots lobbying had a longer history in the US, where there is a mandatory lobby register, civic mobilization by companies is relatively new to the rest of the world, where lobbying regulation also tends to be lax.[11]

Corporate grassroots lobbying is becoming a viable career. The professionalization of techniques such as community organizing in the third sector and electoral campaigning, and the higher salaries available in the private sector, is driving the increase in the use of these practices.

Corporate grassroots lobbying practices are developing rapidly in the platform economy and becoming increasingly important in corporate public affairs, yet they currently operate without regulation or public awareness.

Proud or Ashamed? Airbnb’s Response

In March 2021, in response to the findings of the research, Airbnb’s official response was “We announced the creation of Host Clubs at a press conference in 2015. Host Clubs have always worked closely with our teams to advocate on behalf of the Airbnb community and we are incredibly proud of this work.”

Yet recently, Airbnb have deleted many of their pages dedicated to Home Sharing Clubs, including their misleading FAQ document and the site where it was hosted, airbnbcitizen.com. The pages that remain are news items or they ask hosts to join or start a Facebook group instead. It remains Airbnb who chooses these “community leaders” who volunteer to moderate the Facebook pages, and Airbnb appear as sole admins on most Facebook host groups.

Airbnb’s public facing information seems to fluctuate between offering materials that shown to be misleading, or hiding the policy from view altogether.

Why Does Grassroots Lobbying Matter?

Platform-sponsored grassroots lobbying is receiving significant investment and playing an increasing role in the fierce regulatory struggles around new digital businesses all over the world. The methods are modelled on civil society, including petitions, protests, media stunts, and community organizing traditions that involve leveraging the “curated stories” of users, one-to-one meetings, and other civil society practices recognizable to activists.

Corporate-sponsored grassroots lobbying also involves using public consultations and legislative hearings designed for citizen participation by businesses who professionally train and prepare activists for these encounters. Practices and forums which have historically been used by citizens or organic grassroots groups with few resources and little power to influence elites and change society have become part of the public policy repertoire for multinational companies in the new digital economy.

Community organizers,[12] often trained by political parties or NGOs, are being employed to carry out this work for businesses. It is imaginable that similar to sponsorship and philanthropy, companies might in some cases sponsor independent civil society organizations in a way that appears to support democratic institutions. Yet there is no evidence for this potential benefit yet.

The companies analysed here risk undermining democratic institutions in the longer term by deploying these practices to lobby for specific favourable legislation, often to neutralize concerns from organic grassroots movements, with little transparency about the companies’ purposes, the nature or extent of their groups’ funding, their membership model, or their implications. As such, they appear to entrench the political power of corporations, and may further undermine trust in democratic processes.

Recommendations and Demands: Transparency and Regulation

The findings feed into six recommendations or demands which could be put to governments by citizens. They circulate around ensuring transparency, safeguarding democratic institutions, and protecting and strengthening civil society. The report suggests:

- Statutory lobbying registers that include grassroots lobbying. It is widely recognized as important that corporate political influence over democratically elected elites needs to be more transparent.[13] Therefore, we follow campaigners in recommending a statutory (mandatory) register of lobbying, as is used in the US and a few other contexts. Funds spent on grassroots lobbying or what is sometimes called “indirect communication” must represent a distinct category, with a spending threshold or a size of business threshold set to exclude citizen campaigns; companies must reveal their civil society “clients”; and the register would need to include in-house as well as consultant lobbyists. It is also crucial that the register includes categories that oblige third party entities (such as home sharing clubs) who get involved in public hearings, consultations, and other processes associated with democratic institutions to list information that show their origins and sponsors.

- Sufficient resources for municipal governments to enforce regulation around new businesses. Local governments often have insufficient resources to enforce regulation that relates to platform businesses. In the case of short-term lettings platforms this means protecting housing stocks from uncontrolled continued expansion of short-term lettings, many of which might otherwise be homes for longer-term residents. Even where housing campaigners have raised their concerns, policy-makers may feel they have little choice but to adopt regulatory options proposed directly by Airbnb’s “Policy Tool Chest”, made specifically for politicians, which may not be in the best interests of their constituents. A growing body of research highlights to city councils the strategies urban platforms are using to secure their legislative interests, and the alternatives that are available.[14]

- Records of meetings between policy-makers and corporate grassroots lobbyists. Thirdly, we call for public records of meetings between politicians and grassroots lobbyists whose participation depended on a funded campaign drive, such as that of Airbnb. Individuals and associations must disclose this private funding and resources in the process of accessing public officials or politicians and records of the frequency and purpose of meetings should be published in order to help identify and differentiate corporate organizing drives from the proper use of these institutions.

- Reviews of public consultations and other democratic institutions being used by private sector grassroots lobbying initiatives in the most affected countries that focus on how democratic and judicial institutions can be better safeguarded against undue influence by corporate interests.

- Analysis of the legality and ethics of the political use of platform data. We recommend the review of the (mis)use of data used for political campaigning gathered by platform economy companies in the course of offering services. Airbnb, Uber, Lyft and JUUL all rely on their access to customer data for their grassroots efforts—data which was initially provided by users for different purposes. According to interviewees, Airbnb subsequently collects significant data about users’ personal lives in the process of “collecting stories”. Questions need to be asked about this collection of personal data and subsequent use beyond its initial purposes, in Europe using GDPR regulations, but of similar ethical significance elsewhere.

- Education, training and campaigns to publicize and problematize corporate grassroots lobbying. Lastly, more work is needed across civil society to further identify and publicise corporate and PR strategies that are being used to neutralize genuine citizen participation and social movements, and to show the contradictions and risks involved for societies.

References and Further Reading

Adamiak, C. (2019). Current state and development of Airbnb accommodation offer in 167 countries. Current Issues in Tourism, 0(0), 1–19.

Airbnb (2018) Salteño pride: Salta Hosts create their first club. Airbnb News (April 13) news.airbnb.com/salteno-pride-salta-hosts-create-their-first-club/ (last accessed 2/21)

Airbnb (2020b). Form S-1/A Airbnb, Inc: IPO Investment Prospectus. sec.report/Document/0001193125-20-306257/ (last accessed 6/2/21)

Airbnb Citizen (2021a). Learn More about Home Sharing Clubs (FAQ document). www.airbnbcitizen.com/clubs/faq (last accessed 15/6/21)

Botsman, R., & Rogers, R. (2010). What’s Mine is Yours: How Collaborative Consumption is Changing the Way We Live. New York: Harper Business.

Chari, Raj; Hogan, John; Murphy, Gary; Crepaz, Michele. (2019). Regulating Lobbying: A Global Comparison (2nd ed). Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Cócola-Gant, A., & Gago, A. (2019). Airbnb, buy-to-let investment and tourism-driven displacement: A case study in Lisbon. Environment and Planning A, 0(0), 1–18. doi.org/10.1177/0308518X19869012

Collier, R. B., Dubal, V. B. and Carter, C. L. (2018) ‘Disrupting regulation, regulating disruption: The politics of Uber in the United States’, American Political Science Association, 16(4). doi: 10.1017/S1537592718001093.

Colomb, C. and de Souza, TM (2021). Platform-based property rentals in European cities: the policy debates. Property Research Trust. www.propertyresearchtrust.org/uploads/1/3/4/8/134819607/short_term_rentals.pdf (last accessed 9/21)

Community Organisers (2020). ‘Community Organising Compared’, available at www.corganisers.org.uk/what-is-community-organising/the-book/ (last accessed 12/20)

Corporate Europe Observatory (2018). UnFairbnb: How online rental platforms use the EU to defeat cities’ affordable housing measures. Available at: corporateeurope.org/power-lobbies/2018/05/unfairbnb (last accessed 12/2020)

Cox, M and Haar, K. (2020). How short-term rental platforms like Airbnb fail to cooperate with cities and the need for strong regulations to protect housing. Study commissioned by members of the IMCO committee of the GUE/NGL group in the European Parliament left.eu/content/uploads/2020/12/Platform-Failures-Airbnb-1.pdf (last accessed 9/21)

European Commission (2016) A European Agenda for the Collaborative Economy. Brussels.

InsideAirbnb (2021) InsideAirbnb: Adding Data to the Debate. insideairbnb.com (last accessed 2/21)

Juul (2021) Juul Action Network. Available at www.juul.com/actionnetwork (last accessed 9/2021)

Lobbying Transparency (2015) International Standards for Lobbying Regulation: Towards greater transparency, integrity and participation. Transparency International, Access Info Europe, Sunlight Foundation and Open Knowledge International. lobbyingtransparency.net (last accessed 2/21)

Lyft Careers (2020a) Community Strategist [job advertisement]. Available at boards.greenhouse.io/lyft/jobs/4837326002 (last accessed 25/9/20)

OECD (2013) Principles for transparency and integrity in lobbying. OECD. www.oecd.org/gov/ethics/oecdprinciplesfortransparencyandintegrityinlobbying.htm (last accessed 2/21)

Rosenblat, A. (2018). Uberland: How Algorithms Are Rewriting the Rules of Work. Berkeley CA: University of California Press.

Slee, T. (2015) What’s Yours is Mine: Against the Sharing Economy. OR Books.

Thelen, K. (2018) ‘Regulating Uber: The politics of the platform economy in Europe and the United States’, Perspectives on Politics, 16(4), pp. 938–953.

Transparency International Ireland (2015) Responsible Lobbying: A Short Guide to Ethical Lobbying and Public Policy Engagement for Professionals, Executives and Activists. transparency.ie/resources/lobbying/responsible-lobbying (last accessed 2/21)

van Doorn, N. (2020). A new institution on the block: On platform urbanism and Airbnb citizenship. New Media and Society, 22(10), 1808–1826.

Wachsmuth, D., & Weisler, A. (2018). Airbnb and the rent gap: Gentrification through the sharing economy. Environment and Planning A, 0(October 2013), 1–24.

Wachsmuth, D., Combs, J., & Kerrigan, D. (2019). The Impact of New Short-term Rental Regulations on New York City: A report from the Urban Politics and Governance research group, McGill University, (January), 1–28.

Walker, E. T. (2014) Grassroots for Hire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Yates, L. (2020). Political struggles in the platform economy: Understanding platform legitimation tactics. In M. Hodson, J. Kasmire, A. McMeekin, J. G. Stehlin, & K. Ward (Eds.), Urban Platforms and the Future City: Transformations in Infrastructure, Governance, Knowledge and Everyday Life. London: Routledge.

Yates, L. (2021). The Airbnb ‘Movement’ for Deregulation: How Platform-Sponsored Grassroots Lobbying is Changing Politics. University of Manchester and Ethical Consumer Research Association. www.research.manchester.ac.uk/portal/files/192396608/Yates_2021_The_Airbnb_Movement_Corporate_Sponsored_Grassroots_Lobbying_in_the_Platform_Economy.pdf

Zuboff, S. (2019) The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. London: Profile Books.

[1] See Colomb et al 2021.

[2] See Yates 2021.

[3] Airbnb Citizen 2021a.

[4] European Commission 2016: 2.

[5] Adamiak 2019. Other data sources, e.g. Cox and Haar 2020, show that revenue from commercial operators outweighs that of home sharing by an even greater margin.

[6] e.g. Cox and Haar 2020, Wachsmuth and Weisler 2018.

[7] Airbnb Citizen 2021a.

[8] See Yates 2021.

[9] See Airbnb 2021a.

[10] See Yates 2021.

[11] See Chari et al 2020.

[12] Despite Airbnb using the same name for their practices, there are critical differences between corporate organizing and community organizing. This is illustrated by examining how “community organizing” is described by third sector organizations in their materials and comparing Airbnb’s practices (Community Organisers UK 2020). Corporate “grassroots” organizing practices are 1) not directed at injustices and inequality. There is 2) not a commitment to “challenge vested interests and unjust power”. The practices are 3) not inclusive—ignoring stakeholders who are concerned about business practices and carefully selecting certain representatives for campaigns, and 4) the practices potentially endanger rather than “uphold public trust and confidence”.

[13] e.g. OECD (2013) “Transparency and Integrity in Lobbying”.

[14] See especially Cox and Haar 2020, Colomb and de Souza 2021.