In recent years, cultural diplomacy has become an integral component of China-Africa relations. This development has to a large extent been a result of China’s — as opposed to Africa’s — attempts to promote its culture beyond its borders. It comes at a time when Beijing is aspiring to become not just an active participant in global affairs but also a shaper of international norms. In this endeavour, Chinese traditional culture has been streamlined in both domestic and foreign policies. Since 2013, when the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) was adopted by the Chinese government, Beijing has continued to deepen cultural exchanges with Africa.

Muhidin Shangwe is Lecturer of International Relations in the Department of Political Science and Public Administration at the University of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

Despite a lack of clarity on what exactly constitutes the BRI, which has led to contested interpretations, it is generally understood as an infrastructure project spanning Asia, Europe, Africa, and Latin America through the construction of roads, bridges, ports, airports, transmission lines, and communication networks. Yet the promotion of BRI takes into account elements of Chinese traditional culture for the sole purpose of promoting a “true image” of China and boosting mutual understanding with other cultures. The BRI is thus not just an infrastructure development initiative. In reality, it cannot be discussed outside Beijing’s grand strategies of national rejuvenation (otherwise known as the Chinese Dream), and President Xi Jinping’s idea of building a “community of common destiny”.

Since the adoption of BRI, China has implemented diverse forms of cultural exchanges. Consequently, the promotion of culture has been dominated by activities such as hosting arts, film, and music festivals, cultural exhibitions, book fairs, radio, film, and television programmes. Recently, these activities have been more institutionalized through platforms such as the Silk Road International League of Theatres (2016), the Silk Road International Museum Alliance (2017), the Network of Silk Road Arts Festivals (2017), and the Silk Road International Library Alliance.

This development has resulted in more cultural aid. The construction of the Museum of Black Civilizations and the National Wrestling Arena in Dakar, Senegal are good examples. Elsewhere, the Algiers Opera House in Algeria and the Culture Palace in the Ivory Coast’s capital Abidjan add to the list of China-funded projects. We have also witnessed increasing number of Confucius Institutes (CI) in Africa, totalling 54 in 2018. In comparison, there were only 25 CIs on the continent in 2010.

In countries such as Tanzania, the CI was built along a mega-library at the University of Dar es Salaam at the cost of 41 million US dollars. Media cooperation has seen increased training of African journalists. State-owned media Xinhua, the China Daily, China Radio International and the China Global Television Network (CGTN) have also gained a conspicuous presence in the continent by maintaining bureaus and journalists on the ground.

Education exchanges are also happening at an unprecedented pace, at least before the COVID-19 pandemic. Such exchanges usually happen through Chinese government scholarships to African students and collaborations with local think tanks. In addition, we have witnessed Chinese television dramas being dubbed into African languages such as Kiswahili and Hausa. StarTimes, a private Chinese pay television company has in particular made significant incursions in this area. Most of the dubbing is done in China, all paid for by the company.

Internal Cohesion, External Radiation

To understand China’s cultural diplomacy in Africa, one needs to look at the idea of soft power and how it is understood, adopted, and applied by the Chinese government. But even more importantly, one also must understand China’s “Comprehensive National Power” (CNP) strategy, which, unlike in the West, pays great attention to soft power in general and culture in particular.

The political scientist Joseph Nye identified three soft power resources: a country’s culture, political system/values, and foreign policy. The Chinese, however, define soft power to include the application of a country’s full power resources except the use of military force. From the onset of the soft power debate among Chinese intellectuals and politicians, culture took centre stage. This should be understood in the context of China’s limitations in other soft power resources. For many in China, culture is synonymous with soft power.

The centrality of soft power, and culture for that matter, is premised on its potential to cater to domestic as well as external purposes. Internally, soft power is seen as useful in building and sustaining internal cohesion in a vast country of 56 ethnic groups. Externally, soft power intends to project a positive image of China and strengthening Beijing’s international standing.

This adoption of cultural soft power for different domestic and foreign purposes is referred to as “internal cohesion, external radiation”. The external radiation of culture, which is the idea of spreading Chinese culture, partly but significantly explains Beijing’s inroad into Africa since the turn of the new millennium. Many observers attribute this to China’s quest for raw materials and access to Africa’s market of more than one billion people.

However, Africa’s potential is beyond Beijing’s economic motives, as it includes the political capital bestowed on its 54 countries. Africa’s political support has immensely contributed to Beijing’s international standing, starting with the restoration of China’s seat in the United Nations in 1971. Today, China can, on the whole, count on African countries for support, including refuting allegations of human rights abuse.

China-Defined Cultural Exchanges

On the whole, the cultural exchanges between China and Africa are driven by Beijing. The scope of exchanges therefore depends on China’s capacity and willingness to finance cultural activities, weakening African agency in the process. According to one source, China spends 10 billion US dollars on soft power every year, therefore it is only right that a good part of that sum will be directed to Africa. The implication of this massive investment is that China has managed to leave its cultural imprint on the continent.

One of these imprints is the presence of the Confucius Institutes. Yet the teaching of Chinese language is moving beyond these Institutes. In Tanzania, Chinese language has been introduced in selected schools. Similar development is happening in Uganda, Kenya, and South Africa where efforts to integrate Chinese language in school curricula have taken place. Although there are no “Chinatowns” in Africa, Chinese restaurants have in the last few years become conspicuous almost in all African urban centres.

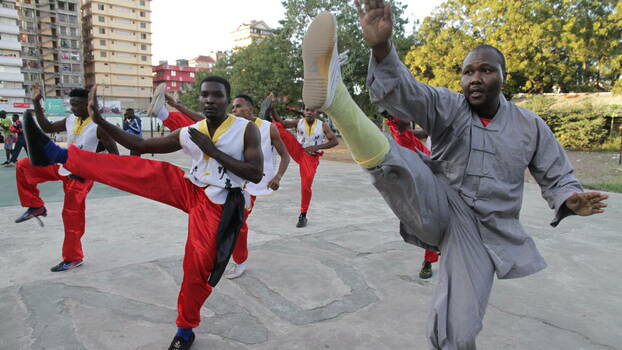

In what has been described as “kung fu” soft power, Chinese martial arts is also gaining appeal across the continent. The once little-known Chinese New Year has gradually been adopted into the national calendars of many African countries, where it is now marked with colourful celebrations. Meanwhile, Africans who study in China and beneficiaries of Chinese government scholarships are returning home with a better understanding of the country, its people, and its culture. They are important in establishing entry points for China now and in the future through guanxi (personal connections), itself a key concept in Chinese culture.

Furthermore, Chinese culture is being showcased in Africa much more frequently than African cultures are being featured in China. This is despite efforts, again by China, to balance the exchanges. The “African Cultures in Focus” series is one of those efforts that showcases African cultures inside China. Over the years, African cultures have registered into Chinese space in the form of performing arts, museums and language. African artefacts can be seen in museums such as one at the Zhejiang Normal University’s African Study Centre. In 2015, the Shanghai Natural History Museum opened its African history section which featured Tingatinga paintings from Tanzania. Meanwhile, Kiswahili and Hausa language courses are offered at Peking University’s African Studies Centre. Moreover, the Jianhua Qiubin Primary School in Zhejiang Province has been implementing special programmes focusing on African culture since 2015.

These efforts are commendable but they in no way match Chinese cultural incursions in Africa. Above all, they are not initiated by African countries themselves. This tendency underscores the fact that cultural exchanges between Africa and China are taking place in an asymmetrical power relation. There is no African equivalent of, say, the Confucius Institute inside China. The proposed setting up of Mandela Institutes has not come to fruition.

But all is not lost for Africa. China’s cultural push means that Beijing is also catering to Africa’s own cultural aspirations. African countries have programmes of their own to support their own cultures, but a weak economic base means that most of them cannot finance such programs. Chinese funding thus offers great opportunity for Africa to meet their own demands while at the same time boosting Beijing’s soft power. The China-funded Museum of Black Civilizations in Dakar, for instance, is consistent with the aspirations of not just Senegal but the global African community.

Likewise, the dubbing of Chinese dramas promotes Chinese culture in Africa, but it also breaks communication barriers — a critical step in establishing mutual understanding between Africans and Chinese. It is in the best interests of Africa to build capacity to engage China. Therefore, any Beijing-driven effort that contributes to that task is welcomed. The weakness of this “strategy” is that these exchanges can only happen within China-defined cultural exchanges. This can be counterproductive for both parties, but more so for Africa and its diasporic populations.