The Chinese digital economy plays a key role in China’s “digital prosperity” (see Article 1). Originally created as a copy of the Californian model, it has since developed into an independent pillar of modern Chinese society. When it comes to user numbers, market dominance, or the amount of data generated, it can now more than hold its own against the originals from Silicon Valley.

Timo Daum is an author and social theorist whose research focuses on digital capitalism.

Translated by Marty Hiatt and Joel Scott for Gegensatz Translation Collective.

Attracting comparable amounts of venture capital to their US counterparts, Chinese digital corporations “are rewriting the rules in China, changing the country in the process, and creating a market that will, over time, have an enormous impact in the rest of the world”, writes Edward Tse, a renowned expert on Chinese economic development.

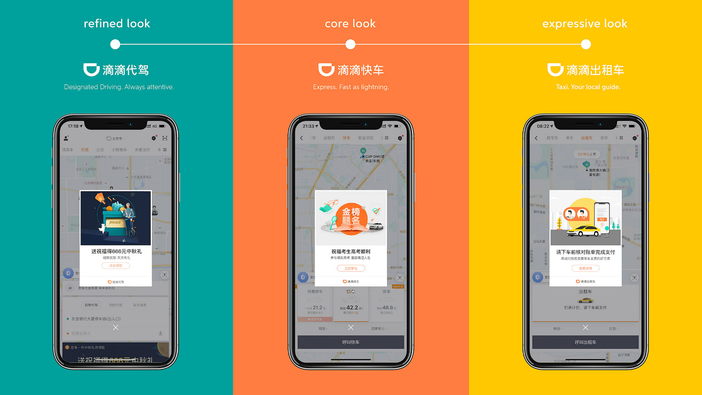

The big three are Alibaba, Baidu, and Tencent (the A–B–T of the China’s digital economy), but ByteDance (TikTok) and many others like Didi Chuxing, which arranges private taxi rides, have also become mega-corporations that shape China’s digital society. At the same time, the Chinese digital economy is much more dependent on, and intertwined with, the country’s official digital policy and the goals of the party leadership.

Chinese digital corporations have become independent centres of power in Chinese society and their bosses immeasurably rich. In what is still “the world’s largest developing country” according to president Xi Jinping, this is increasingly seen as a problem. The party leadership has even declared the mitigation of “uneven development” to be the central contradiction for Chinese society to tackle.

How Did It Start?

Shortly after the internet age began in China, the first Internet companies emerged. In 1998, Tencent was founded in Shanghai. Shortly thereafter, in February 1999, Tencent’s QQ app was launched. It was the first widely used messaging app in China, replacing SMS as the standard mobile messaging service, which involved messages being handled by telephone providers for a fee. QQ is still widely popular today, with around 1.3 billion monthly active users (MAU). Tencent is also the company behind for WeChat, which was launched in 2011 and is perhaps the most important everyday app in China.

Also in 1999, Jack Ma founded Alibaba, a wholesale e-commerce company, which has become a trade and finance giant, currently boasting 939 million MAU. In 2003, Alibaba launched Taobao, a trading platform that provides an online marketplace for private individuals and small traders and producers. That same year, with its services proving better tailored to the specificities of the Chinese market, Alibaba outperformed US competitor eBay, which eventually exited the Chinese market. Alibaba’s Alipay was launched in 2004 and triggered a boom in online payments. The clincher: the platform manages payments in trust until the customer is satisfied with the product.

Baidu was founded in 2000. Its core business is the operation of the world’s second-largest search engine after Google, with a domestic market share of 76 percent. Google withdrew from China in 2010. The founders, software developer Robin Li Yanhong and biologist Eric Xu Yong, became multi-billionaire internet entrepreneurs.

The Chinese digital economy has matured and its apps are well-established. Although the applications were often initially created as copies of Californian originals, they nevertheless managed to achieve a dominant market position in China.

Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent make up the “big three” digital corporations in China.

In 2009, Sina Weibo from Shanghai launched Weibo (“microblog”), now the largest microblogging site in China and often referred to as China’s Twitter. After Twitter was banned in China, Weibo took up the slack. It currently has 426 million MAU.

In September 2016, Douyin, a short-form video app by Beijing-based company ByteDance, first appeared under the name A.me. With 613 million MAU, it is the most successful Chinese video app. Just one year later, a variant for the international market was launched: it goes by the name of TikTok.

The beginning was quite rocky for ByteDance and its founder Zhang Yiming. As late as 2018, the company’s first successful app, Neihan Duanzi (“implied joke”), was banned for hosting content critical of the regime.

WeChat: Popular and Insecure

WeChat, or Weixin, as it is known in China, is the country’s undisputed number one everyday app. Ninety percent of all Chinese internet users access this central app by Shenzhen company Tencent every day. WeChat started out as a bare-bones messaging app, and to this day does not provide read receipts.

WeChat is similar to WhatsApp in many ways, but goes beyond it in terms of functionality. Zak Dychtwald writes: “without quitting WeChat, you can use [features like those of] Facebook, Instagram, Skype, WhatsApp, Yelp, Venmo, ApplePay, Groupon, Uber, parts of Amazon, and a whole host of other apps”. These range from reservations and concert tickets to bitcoin deliveries and transport services.

WeChat “moments” are very similar to stories on Instagram, while “channels” deliver short videos like TikTok. An important feature are the mini-programmes introduced in 2017, which run within the app and allow users to interact with other services. These mini-apps load quickly, as they don’t need to be installed through the App Store, turning WeChat itself into an app platform.

With 1.5 billion messages sent daily, 1.26 billion MAU, and 3 million companies using WeChat for business, WeChat is currently the world’s number-one instant messaging application. It now serves as a social media platform combined with numerous applications for services such as e-commerce and payments. WeChat Pay processes over one billion transfers every day.

Unlike WhatsApp, WeChat messages are not end-to-end encrypted. User data is made available to the Chinese authorities upon request, who can in principle read not only the metadata (who, when, to whom, etc.) but also message content. In terms of data protection, one of the most popular apps in the world has serious issues. The Mozilla Foundation even advises against using it altogether, which is presumably out of the question for Chinese people. The Mozilla Foundation lists incidents such as leaks of hundreds of millions of private chat logs, recently reported bans on LGBTQ-friendly and feminist accounts, and alleged surveillance by Chinese government agencies as “deal breakers”.

Mobile Payments Replace Cash

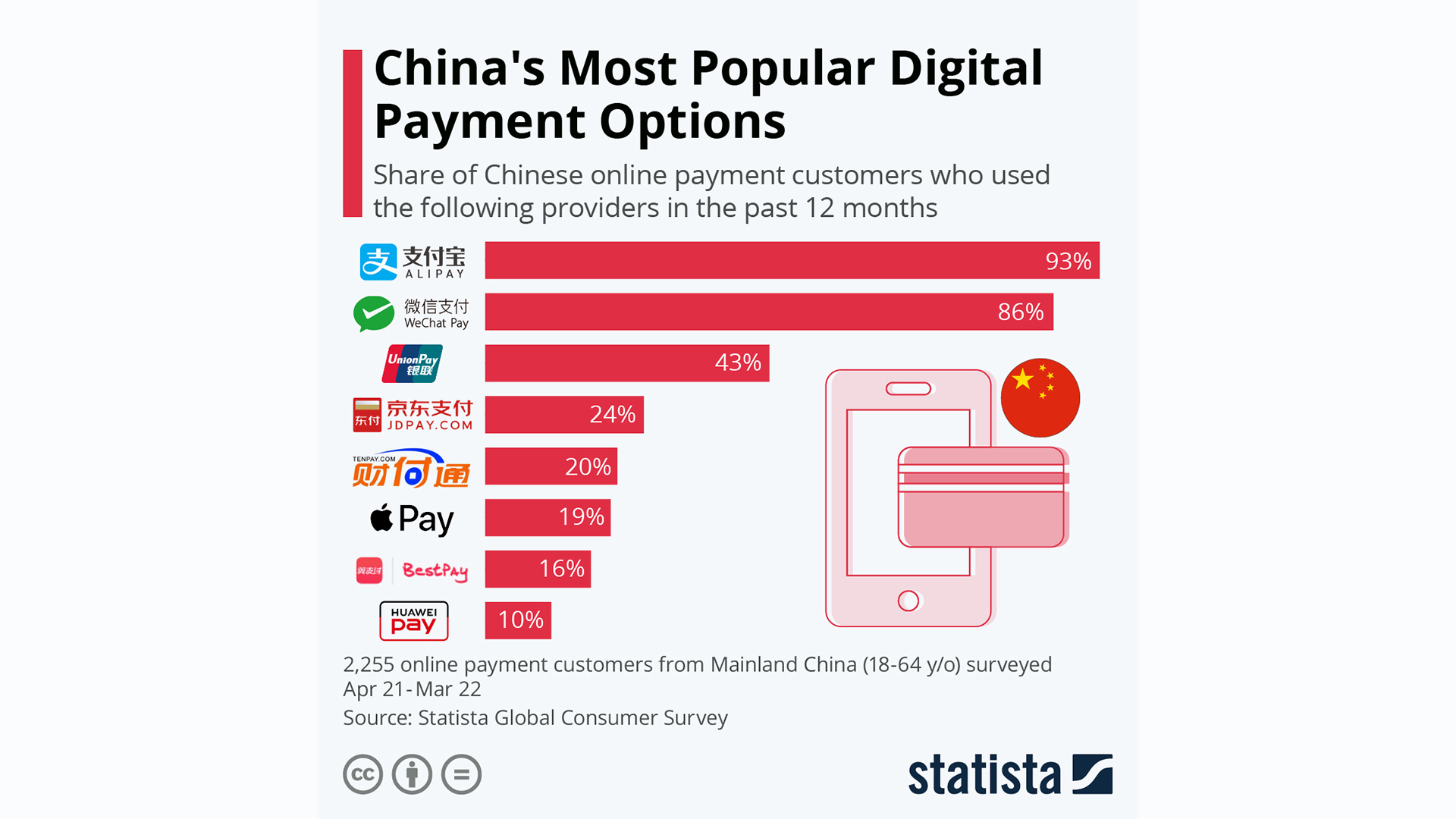

The standard question when paying for all kinds of goods and services, including at street stands and in taxis, is: “Alipay or WeChat?” Chinese payment apps are extremely popular. As of December 2020, there were around 852.5 million unique users of mobile payment apps in China. In 2020, the number of mobile payment transactions in China grew to around 123.22 billion. Alipay and WeChat Pay have largely replaced cash.

Contactless payment using QR codes is standard in China. It is completely normal to use your smartphone to pay for event tickets, train tickets, or hotel rooms, whether booking online or off. Splitting bills between friends and sending “red packets” (via WeChat), a Chinese tradition of sending small gifts of money on certain occasions, is also part of everyday life. Alipay, by Hangzhou-based Alibaba, is the most popular payment app, with currently 640 million MAU.

Google’s open-source Android operating system is dominant in China, being used on 80 percent of all smartphones — a figure similar to the rest of the world. Since the Google Play store is not available in China, a large number of other app stores fill the gap. The leading app store is the Huawei AppGallery, which currently has 530 MAU.

Developments during the Pandemic

China became the first country in the world to release a nationwide contact-tracing app in February 2020. The Health Code app was developed by Alibaba and Tencent. Users access it via Alipay or WeChat, and it registers their full name, phone number, and an ID card. It stores personal data such as travel history, address, and medical records. The application documents the person’s health status in real time and generates a QR code that identifies their risk level as red, yellow, or green.

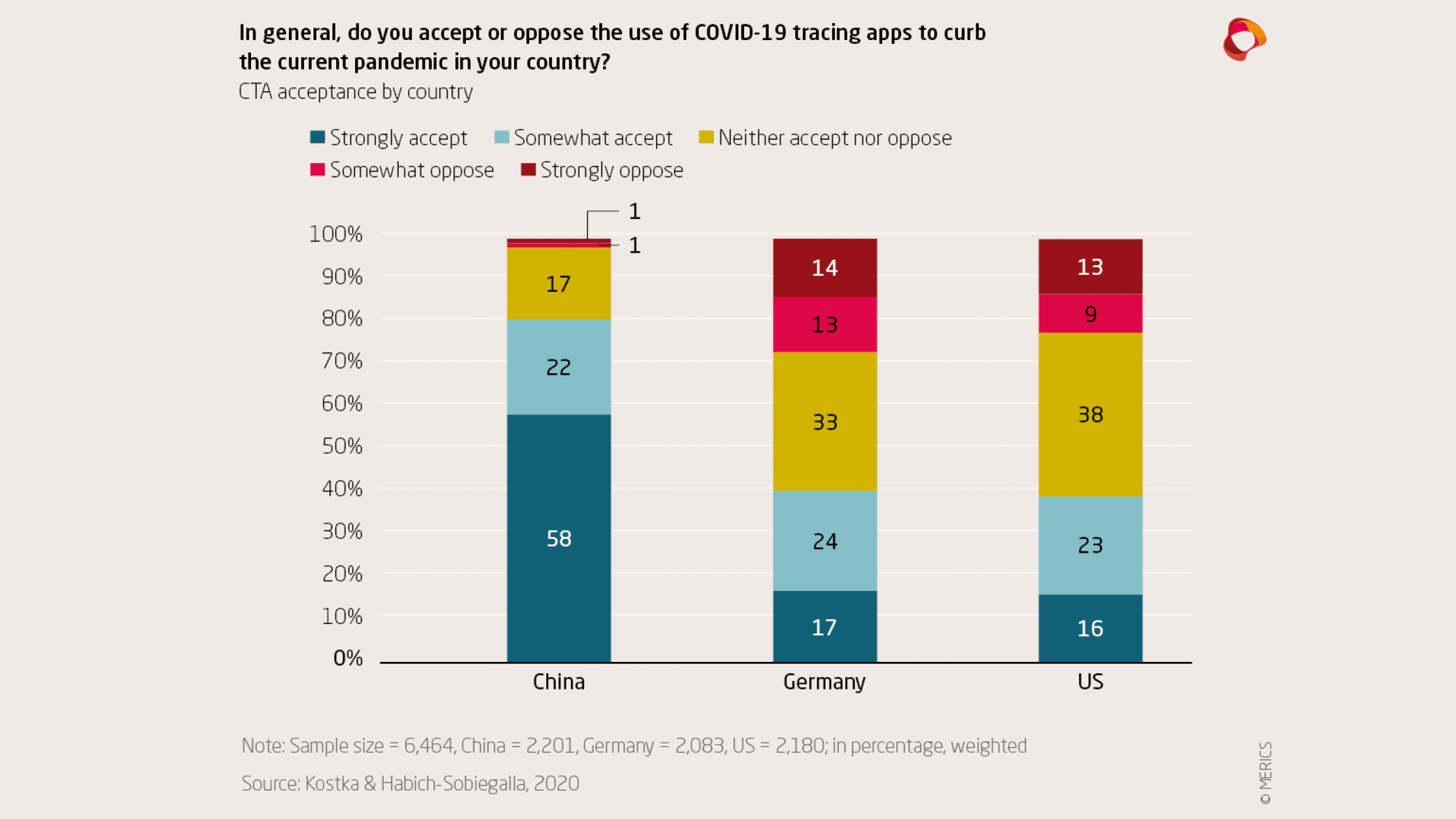

Yet the app is prone to abuse. Although it is against the law to change the app’s status on anything other than medical grounds, there have been reports of individuals or groups being forced to change their status for political reasons, leading to restrictions on their freedom of movement. Nevertheless, the apps enjoy a high level of acceptance in China, with 80 percent of people reporting feeling mostly positive toward them, whereas the figure is only 39 percent in the US and 41 percent in Germany.

Chinese app companies have now consolidated their position in the world’s largest domestic digital market.

By contrast, in Germany, COVID apps were only developed much later, and their design and handling of data was characterized by anonymity, being voluntary to use, and data protection considerations. Yet their acceptance and actual usage levels lagged far behind their Chinese counterparts.

This development illustrates the close dovetailing of national health policy with the services of private companies and, conversely, the willingness of the latter to act in service of, or subordinate themselves to, China’s official campaigns, activities, and socio-political objectives. This only intensified in the course of the pandemic.

That has become a significant economic factor. In Hangzhou, a joint venture between e-commerce group Alibaba and two state-owned companies was recently awarded a 12-month contract to operate the contact-tracing system, which is designed to handle 25,000 queries per second.

Conquering the Global Market

The Chinese digital economy has matured and its apps are well-established. Although the applications were often initially created as copies of Californian originals, they nevertheless managed to achieve a dominant market position in China — not least through its policy of isolation, which prompted the US competition to withdraw from the country at an early stage. They have now consolidated their position in the world’s largest domestic digital market. After a phase of copying and of isolating the domestic market, followed by a phase of domestic growth and consolidation, a third phase now follows: conquering the global digital market.

The most successful example of this internationalization to date is TikTok. ByteDance’s variant of DouYin aimed at the international market has been available in the Apple Store and Google Play since September 2017. Since then, TikTok has been downloaded a total of 3 billion times worldwide, and no other app has reached the one-billion-user mark as quickly as TikTok. Currently with around 1.4 billion MAU, it is one of the most successful apps of all time.

TikTok represents a third phase in the development of the Chinese digital economy. Alongside WeChat, TikTok is a world-renowned example of a Chinese app that has liberated itself from its predecessors and forerunners in Silicon Valley. The 37-year-old founder Zhang Yiming stressed in a recent interview: “we are not a copycat of a US company, neither in terms of the product nor in terms of technology”. Samm Sacks from the Center for Strategic and International Studies states: “[...] China’s internet companies are no longer mere ‘copycats’ or clones of western companies [and] Chinese internet companies are making a strong push to expand to global markets”.

Indeed, international companies are now trying to identify trends in China and take on ideas from Chinese start-ups.

![[Translate to en:] Grafik: Social-Media-Plattformen im Vergleich zu fast 4,66 Milliarden aktiven Internetnutzer*innen (59 Prozent der Weltbevölkerung) im Jahr 2020](/fileadmin/images/Ausland/China/Screenshot_from_2021-02-01_10-44-15.png)