“Get your eggs here!” shouts the man walking briskly through Parque Céspedes, the main square in Santiago de Cuba. Two women approach him, others soon follow.

“How much?”

Federico Mastrogiovanni is an Italian journalist who has lived in Mexico since 2009. He was honoured with the Mexican PEN Association award for his book Ni vivos ni muertos (Penguin Random House, 2016).

Translated by Michael Dorrity and Joseph Keady for Gegensatz Translation Collective.

“1,800 pesos, mima.” That’s a little more than 10 US dollars on the street, where you might get 170 pesos for a dollar. Three eggs for a dollar. In a country where 30 dollars per month is very good salary, a carton of eggs costs ten.

The man holds a carton of 30 eggs in his left hand and a mobile phone in his right. Barely a minute passes before the eggs are all sold. One of the most widely consumed foods in the world (given its high protein content and low cost) is a luxury that the average Cuban cannot afford, and the presence of which on a breakfast plate is a sign of serious purchasing power.

In Cuba, it seems, any old hen lays golden eggs.

Culinary Wizardry

Shortages are an extremely important and highly relevant issue on the Caribbean island. The reasons for the high price of eggs in Cuba are part of a series of events that impact the diets and daily lives of the people who live there.

For starters, industrial chicken feed is in extremely short supply in Cuba. It is too expensive, because it has to be imported. In 2022, Cuban hens did not have enough feed to produce eggs, while their chicks did not have enough feed to survive. Many chicks died, fewer hens were born, and as a result, those that were born did not produce enough eggs to meet the population’s needs. The few eggs that exist have become a rare commodity — and as we know, scarcity drives up prices.

While a carton of eggs costs 1,800 pesos in Santiago de Cuba in the east of the island, the price in the capital, Havana, can reach 2,200 in the run-up to Christmas — almost 13 dollars.

Carlos runs a bar where he serves breakfast on Calle Heredia in Santiago de Cuba. Every day, he has to come up with some sort of substitute for eggs so customers don’t notice that the most important part is missing. Some days, he makes sausage sandwiches, on other days it’s fruit salad and banana, and when there actually are eggs, he performs magic with them.

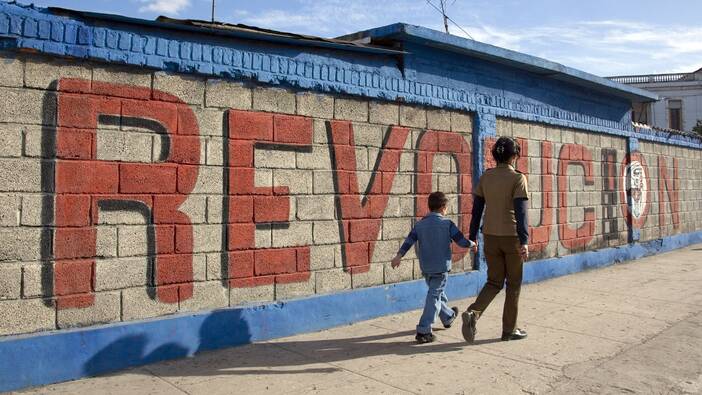

Waiting in line is part of everyday life in Cuba.

“You’ll see how far I can make an egg go.” You can beat an egg with a little onion to fill it out and make the plate look full, or you can make very thin tortillas that take up the whole plate.

In Cuban homes, recipes change according to the shortages. No one has seen a potato in months, so people use other tubers like malanga instead. People also drop carrots or fresh milk from their diets. The croquettes aren’t made with béchamel anymore, because there’s no milk, butter, or flour. “The flour you get often tastes like cockroaches”, is Carlos’s pointed opinion. It appears to have come from a warehouse, but it is old.

Complicated Causality

There are degrees of scarcity in Cuba: some products do not exist at all, and others are hard to find. The absence of products is very clear. You need only go into the stores to find out that you cannot buy them in either the local or the freely convertible currencies that Cubans acquire through the parallel foreign currency circuit.

There is a lack of basic everyday commodities like soap, toilet paper, and shampoo, as well as foodstuffs like oil, chicken, and sausages. But there’s also a lack of other types of basic goods, like raw materials to produce medicine, paper to make books and educational materials, and basic medical supplies like gauze, gloves, and syringes. Even supplies for teaching art and music are in short supply, including musical instruments or oil for painting, and there is little fuel for certain basic services.

According to Ernesto Teuma, professor of political theory at the Instituto Superior de Arte in Havana, the reasons are multi-faceted:

The first aspect, in the broad scheme of things, has to do with Cuba’s specific place in the global economy. It’s a small island state in the Caribbean, a medium-sized economy, underdeveloped, dependent, and its main sources of income — services, certain natural resources, and tourism — are all very fragile in terms of their volatility on the international market.

The tourist industry was completely paralyzed during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. In an initial sign of recovery, the country welcomed some 400,000 tourists in 2022, mostly from Russia. However, that is still a long way from the 4 million who visited in 2019:

Added to that are the difficulties people have accessing food, as prices have increased globally, or difficulties accessing fuel, and inflation, something every country in the world is dealing with one way or another right now. But in Cuba’s case, there is another layer of difficulty on top of that: the effects of the US embargo, which prevents the country from easily and cheaply accessing countless products in what ought to be its natural markets in Latin America and the US itself.

Professor Teuma mentions food, medical supplies, and raw materials for medicine. Access to all these goods has become very difficult due to the laws and regulations behind the embargo (in Cuba, it’s called el bloqueo, “the blockade”) that the Trump administration put in place and the Biden administration has continued:

For an economy that has been hit by the effects of a global recession and therefore has a fairly small economic margin for error, the knock-on effects of the sanctions mean that any shortage whatsoever causes a maximum degree of difficulty. For example, products that would be available on the North American market have to be purchased much further afield, such as in Asia. Obviously, this multiplies the costs in terms of time, freight, and even the quality of the products, which cannot be top of the line and are instead second or third rate.

The third aspect has to do with the unequal impact of current shortages. The difference between the capital and the other inland provinces is significant. Havana is the largest city and enjoys some extra products, while provinces further inland receive fewer basic goods, including those that are subsidized and administered by the state. Products that make it to Havana do not make it to Cienfuegos, Holguín, or Guantánamo. What’s more, in the capital itself, there are differences in shortages between one district and the next.

Diverting Medicines

Hospital medication is sold on the street a few blocks from the centre of Santiago. You can buy boxes of ceftriaxone. The web page of the national pharmacopoeia classifies it as a “life-saving medicine”, while its distribution level is described as “for hospital use only”. It is the antibiotic of choice for very serious infections and for both pre- and post-operation antibiotic treatment. Used indiscriminately, it can cause problems. Moreover, it is administrated intravenously and is not available in pharmacies. How does it make its way onto the streets?

We have something called the basic table of medications, where you have anti-hypertensives, anti-diabetics — medicines that people need and are very important for their quality of life are always guaranteed and were always in the pharmacies. They’ve been in short supply recently, to the point where today, if you need to get a hold of certain medication, you get it on the street.

Leonardo is in his last year studying medicine at the Universidad de Oriente in Santiago de Cuba. In the last few years, he has noticed changes in public health administration in terms of shortages and medication.

The shortages have had troubling effects on the health care sector, which had been on the forefront of the fight against COVID-19, producing vaccines such as Abdala, Soberana 02, and Soberana Plus. According to the Cuban Ministry of Public Health, the vaccines were administered to a combined total of 43 million people by the beginning of 2023.

Global factors may not improve living standards and access to basic staple products and supplies. Thus, the plan to internally organize the Cuban economy is extremely important.

The island manufactures practically all the drugs included in the basic table of medications, including diuretics, anti-hypertensives, and many antibiotics. BioCubaFarma produces medicine both for national consumption and international sales. Yet in Cuban hospitals, medicines are starting to disappear.

Medicines are disappearing at various points along the supply chain. Not everything makes it to hospital shelves, and not all of what does arrive makes it into doctors’ hands, because it’s diverted onto the streets.

In other words, medicines are stolen by employees, carriers, nurses, and doctors, and sold on the black market, leaving the hospitals with shortages.

They’re selling medicines from other countries on the streets, from Russia — you can tell by the packaging. But you’ll find people selling medicine made in Cuba, and that can only have been taken from the hospital itself.

In Cuba, recently graduated doctors earn 4,200 pesos per month at the most, or just a little under 25 euro. For that, you can buy two-and-a-half cartons of eggs. A civilian doctor who has completed the most advanced studies possible earns 8,000 pesos a month, or four-and-a-half cartons of eggs. A doctor who wants to earn more has two options:

They can do business on their own or work abroad. There is no legal way for a doctor to earn more, to earn enough to live with dignity in this country. For example, when we buy chicken here, we buy a box of chicken, and a box of chicken costs more than a doctor’s salary. Right now, it costs 6,000 pesos and weighs about 20–25 kilograms. It might last you a month depending on the size of your family. A pair of shoes might cost you 7,000 pesos. If you think of it in dollars, we earn 30 dollars per month. It’s nothing.

Cuba Has a Plan

In light of this situation, significant measures are being taken.

The first is to stabilize the production of electricity. This will allow several industries to produce essentials in Cuba itself. Until now, many industries had been paralyzed in order to save energy and reduce the effects of energy shortages on the residential sector.

The second measure is to create incentives for foreign investment, especially in the Mariel Special Development Zone, so that these types of goods and services can be produced by way of international value chains. There has been a global call to condemn the embargo and, more recently, President Miguel Díaz went on an international tour in an effort to reduce Cuba’s debt to certain countries, secure investments, and strengthen cooperation.

A plan focusing more specifically on the domestic level has also been developed. These measures have mostly concerned what has been called the “confrontation” with economic crime and corruption, meaning the diversion of enormous quantities of merchandise from state-run companies and markets toward the private sector or informal sale. Rationing has also been better organized, both in the rationing system itself — namely in the bodegas and other state-run retail establishments — as well as in certain stores and certain fields, and for certain types of products, in the case of the market in the national currency.

Are these measures enough? Of course not, because they are being enacted against a backdrop of rampant inflation, which, as a global phenomenon, affects most people’s purchasing power and slows economic activity in general by reducing consumption. According to certain projections, 2023 will be a year of global economic recession and economic contraction in Latin America. Global factors may not improve living standards and access to basic staple products and supplies. Thus, the plan to internally organize the Cuban economy is extremely important.

Waiting for the Chickens to Roost

There is a line of almost 50 people standing outside the entrance to the store Panamericana on Avenida Francisco Vicente Aguilera. They are waiting for the staff of the state-run company to start letting customers in three by three.

Waiting in line is part of everyday life in Cuba. You wait in line at the Panamericana, you wait in line to buy a cut of pork (known as macho in Santiago), you wait in line to get on the bus or to eat at a restaurant. Nobody complains. It’s an intrinsic part of everyday life.

When you arrive, you ask who is last in line and accept that you will have to wait. There is very little on the shelves of the Panamericana: jars of Mexican beans, jars of Spanish canned fruit, 60-dollar bottles of wine, shampoo, seed oil. Today, however, people have gathered because word has spread that there is chicken and yogurt. Nobody knows when they will be available again, so people drop everything to get in line. Maybe tomorrow, a lot of people will have some good soup with a side of rice and beans and a nice juicy chicken leg.

It will have been worth the wait.