On 5 December 2023, South Africa will mark a decade since the passing of national hero and international icon Nelson Mandela. Mandela was a lifelong political activist and leader of the struggle against apartheid, the institutionalized system of total social, political, and economic racial segregation in force from 1948 to the early 1990s. He later became President of both his political party, the African National Congress (ANC), and of the Republic of South Africa after apartheid was abolished and multi-racial democracy introduced in 1994.

Dale T. McKinley is an independent writer, researcher, lecturer, and long-time political activist. He is presently the Research and Education Officer at the International Labour, Research and Information Group in Johannesburg.

The anniversary of his passing provides a fitting opportunity to assess the legacy of a man whose life was — and remains — a source of fulsome praise and inspiration as well as trenchant criticism. But before entering into that contested terrain, it is important to remind ourselves of the key markers that constituted Mandela’s life journey and which together shaped his personality, socio-political views, and overall ideological framework.

A Life in the Struggle

Born on 18 July 1918 into the Madiba clan in the village of Mvezo in South Africa’s Eastern Cape Province, Rolihlahla Mandela was the son of the main counsellor to the Acting King of the Thembu people. The Thembu are a Xhosa-speaking people who emerged as a unified ethnic group during the early nineteenth century, later becoming an independent kingdom until their conquest by the British in the late 1880s. After his father died when he was 12, Mandela became a ward of the King.

The young Mandela successfully completed his primary and secondary schooling at church-affiliated institutions in the province, but was then expelled from the University College of Fort Hare, where he met his life-long friend and comrade Oliver Tambo, in 1940 for taking part in student protests against the quality of food and interference in student elections. He subsequently moved to Johannesburg where, after a stint as a security guard in a mine, Mandela completed his internship at a legal firm and finished his Bachelor’s degree at the University of South Africa

In 1944 he married Evelyn Mase, the cousin of Walter Sisulu — another close friend and comrade — and proceeded to join South Africa’s oldest and largest black nationalist organization, the ANC. Alongside Tambo and Sisulu, he was instrumental in forming the ANC Youth League (ANCYL), through which he soon ascended to become a leader of the Defiance Campaign, a movement of mass civil disobedience against racial segregation launched in 1952.

After a short stint running South Africa’s first black-owned law firm with Tambo in the early to mid-1950s, Mandela was arrested along with many other leaders of the ANC and allied organizations as part of the infamous five-year Treason Trial, charged with plotting to overthrow the apartheid state. During the trial, Mandela divorced his first wife and married social worker Winnie Madikizela.

During the last few years of his imprisonment, the campaign for his release turned Mandela into the public face of the ANC and the international anti-apartheid movement.

Mandela’s life took a decidedly different turn after his 1961 acquittal. He joined the ANC’s underground wing and, after a planned national strike was called off, became one of the first leaders of the ANC’s newly formed military wing, Umkhonto weSizwe, or “Spear of the Nation”. After spending a few months abroad receiving military training and raising support for the armed struggle, Mandela was arrested in August 1962. He was eventually charged with sabotage along with other ANC colleagues in the Rivonia Trial. Specific charges included engaging in “violent revolution” and “furthering the objects of communism”. In June 1964, they were all convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Mandela spent the next 26 years in various prisons. Eighteen were spent on Robben Island, South Africa’s first-ever political prison dating back to the 1700s, when it was used to incarcerate opponents of colonial rule. During the last few years of his imprisonment, the campaign for his release turned Mandela into the public face of the ANC and the international anti-apartheid movement. This newfound celebrity opened the door for him to engage in various “behind the scenes” negotiations with representatives of the apartheid state about dismantling the apartheid system, making him the primary conduit between the white ruling class and the ANC.

Leading the Way to the (Com)promised Land

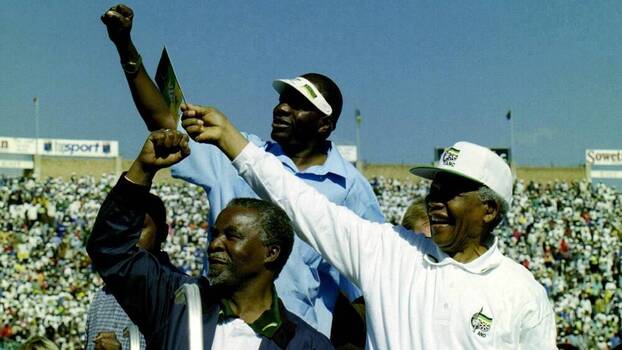

By the time Mandela was released from prison on 11 February 1990, he had effectively assumed the mantle of leadership in the ANC once more and been moulded into the physical incarnation of the organization and its struggle for freedom — hastened by Oliver Tambo’s debilitating stroke in August 1989. Both politically and organizationally, Mandela emerged as a moral beacon and symbol of hope for the majority of black South Africans and millions more across the globe.

The first formal talks between the ANC and the apartheid state began in the weeks that followed Mandela’s release, taking the form of a series of personal meetings between South African President Frederik Willem de Klerk and Mandela. This sent a clear signal that much of the early negotiations would be dominated by personalized engagement between the two “big men”, as opposed to a more democratic, collective process — a trend that continued until a final political agreement was reached over three years later.

Even if it did not appear as such at the time, the personalized nature of the negotiations was hugely important for two reasons: it cemented Mandela’s almost supernatural status outside and beyond the democratic collective of the ANC and its allies, the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) and the Communist Party (SACP), and laid the foundations for what were later to become a series of secret negotiations around post-apartheid economic policy involving a select group of ANC leaders and representatives of domestic and foreign capital.

The most glaring contradiction in Mandela’s legacy is the historic trade-off that he played such a central role in introducing and institutionally managing: namely, the gaining of democratic legitimacy alongside political control of the state without a corresponding transformation of the socio-economic base.

Around the same time, Mandela set off on the first of many foreign trips, during which, as the political and moral symbol of South African’s liberation struggle, he was feted as a hero wherever he went and fawned over by heads of state. While this was to be expected given Mandela’s personal sacrifices and disarming humility, it opened up organizational and ideological space for him to walk back long-held and popular ANC policies such as nationalizing the mines, the financial institutions, and the commanding heights of the economy. It also facilitated his hypocritical and unapologetic acceptance of large amounts of funding for the ANC from the likes of the Suharto military dictatorship in Indonesia and the autocratic monarchy of Saudi Arabia.

These moves were not widely reported on in South Africa, but even if they had been, they would have been overshadowed by the ongoing killing of thousands of ANC activists, workers, and civilians by the apartheid state and its proxies in the early 1990s. Mandela remained hugely popular and virtually immune from criticism at home. For the majority of black South Africans, he continued to represent hope and the possibility of a better political and socio-economic future following lifetimes of suffering and repression at the hands of the white minority government.

These loaded expectations often trumped the conflicting realities established by decisions Mandela and the ANC leadership made. Some examples of these include the 1993 agreement with the International Monetary Fund to accept a massive loan of 850 million US dollars in exchange for committing any future government to a range of corporate-friendly macroeconomic policies, along with the ANC’s highly contested decision to honour the massive and illegitimate debt incurred by the apartheid state.

After a decades-long journey from a revolutionary life as a youthful activist, mass organizer, armed underground operative, and imprisoned liberation movement leader, Mandela’s re-emergence was framed by the embrace of a decidedly reformist politics — even if Mandela (and a majority of the ANC leadership) no doubt considered such a transition to be a pragmatic choice dictated by the prevailing circumstances.

Power to Whom?

By the time the April 1994 elections rolled around, the ANC, thanks in no small part to Nelson Mandela, had managed to exert overall political and ideological authority over what were popularly referred to as the “liberation forces” and the majority of the population supporting them. The ANC’s subsequent overwhelming electoral victory and Mandela’s election as the first democratically elected President of South Africa confirmed this dominance.

Understandably, South Africa witnessed an outpouring of genuine celebration, joy, and optimism, with Mandela occupying centre stage. However, despite this electoral success and the subsequent adoption of a highly progressive constitution, Mandela’s ANC was already well on its way from a party of mass democratic resistance supported by the broad majority to a party of government, increasingly interwoven with the state and economic elite.

In order to try to justify — or, more accurately, conceal — this transformation, Mandela made the astonishing argument that the path to power they had chosen had nothing to do with ideology, since it “would split the organization from top to bottom”. This claim was patently absurd, a truth that was soon confirmed when Mandela and the ANC unveiled a clearly capitalist, neoliberal macro-economic policy framework, the Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) programme in 1996.

Driving home the point that they wielded ultimate state power, Finance Minister Trevor Manuel followed by President Mandela himself declared that GEAR was “non-negotiable”. Although the programme was loudly and publicly opposed by many progressive civil society organizations as well as the ANC’s key allies, Mandela and the ANC dismissed the criticism and in doing so buried the possibility of a different post-apartheid economic path.

This duality persisted throughout the remaining years of Mandela’s presidency. On the one hand, he oversaw some positive, albeit limited achievements. These included the ushering in of a constitutional, multi-racial parliamentary democracy and a range of civil, political, and socio-economic rights. It also included some progressive legislation that provided a legal framework for the realization, protection, and advancement of certain rights over the next two decades, along with the expansion of certain basic services such as electricity, household access to water and sanitation, tertiary education, and primary healthcare. By 2014, South Africa’s literacy rate had increased from 82 to 94 percent of the adult population, the percentage of people connected to the electricity grid increased from around 50 to 85 percent , and more than 1,600 clinics had been built or upgraded.

While socialists can justifiably be critical of significant aspects of Mandela’s legacy, they should be equally appreciative and respectful of his courage, humility, and life-long dedication to things greater than himself.

On the other hand, the rapid implementation of a wide range of neoliberal economic policies had devastating impacts on the majority of poor and working-class South Africans and narrowed the democratic space. These included the partial or full-scale privatization and corporatization of basic services such as urban transport, national highways, municipal water provision, and several state-owned enterprises such as South African Airways. This trend was exacerbated by the commodification of land redistribution as well as pension funds, a secretive and unnecessary arms deal involving the UK, Germany, and Sweden that opened the door to intensified corruption in the public sector, the institutionalization of patronage and the consolidation of a new economic elite, the weakening and absorption of working-class movements, and a general crackdown on critical thinking and political dissent.

Of course, not all that has happened since the fall of apartheid can be laid at the feet of Nelson Mandela. However, the painful paradox of his legacy is that contemporary South African society is one in which “world-class” salaries, housing, landed estates, educational institutions, recreational facilities, and wealth accumulation for the few exist side-by-side with “world-class” joblessness, shantytowns, landlessness, environmental degradation, poverty, and inequality for the many.

Mandela’s Many Facets

The contradictory nature of Mandela’s post-1994 political and ideological journey parallels the first few years of South Africa’s democratic transition. Arguably, the most glaring contradiction in Mandela’s legacy is the historic trade-off that he played such a central role in introducing and institutionally managing: namely, the gaining of democratic legitimacy alongside political control of the state without a corresponding transformation of the socio-economic base.

What emerged from this fundamental contradiction was (and remains) an approach to liberation oriented towards the existing political and economic structures (i.e., the state and capital) as opposed to the contingent power of the majority of people (i.e., workers and the poor). Where the ANC once spoke of fundamentally transforming the economy and ensuring socio-economic equality and redistribution of wealth and opportunity, it now preaches fiscal austerity, adopts corporate friendly policies, and presides over historically high levels of inequality.

For some, Mandela was a tactical genius, adapting his approach to meet the changed circumstances of the period, whether applied to armed conflict, peaceful negotiation, or democratic governance. For others, his tactical nous was secondary to the strategic and ideological continuity in pursuit of a deracialized accession and incorporation into existing power structures.

While socialists and those who continue to struggle to radically transform South Africa’s political, economic, and social order can justifiably be critical of significant aspects of Mandela’s legacy, they should be equally appreciative and respectful of his courage, humility, and life-long dedication to things greater than himself.

Regardless of where we are and on which side of the proverbial “fence” we might sit, there is certainly one thing we can all agree on: Nelson Mandela’s multi-faceted legacy will continue to have equally multi-faceted relevance for many decades to come.