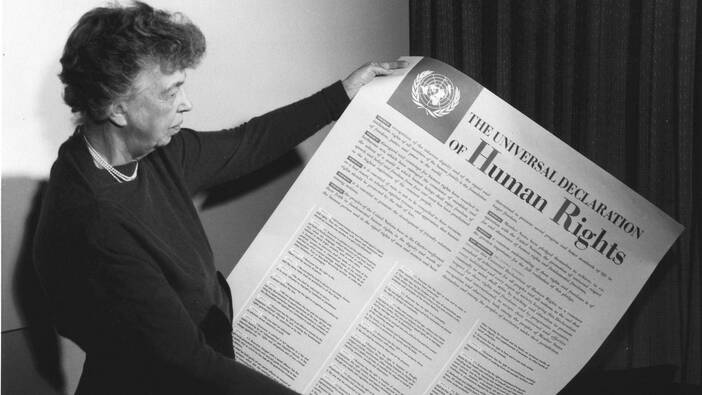

In December 1948, modern Kyrgyzstan was not yet on the map. In its transformation from a Soviet republic to an independent country, Kyrgyzstan set out on its democratic journey, which has included the commitment to respect human rights. This December marks the seventy-fifth anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. After 30 years of independence and on the anniversary of this important document, what is the state of human rights in Kyrgyzstan?

Medet Tiulegenov is a Senior Researcher at the Civil Society Initiative, University of Central Asia.

Kyrgyzstan signed the main human rights treaties at the very beginning of its independence and the country actively participates in the UN’s Universal Periodic Review of its human rights obligations. It is currently also a member of the UN Human Rights Council. For many years, it was this situation that led to Kyrgyzstan being called an “island of democracy” — in comparison with the low level of respect for human rights in neighbouring countries. However, the current human rights situation in the country is particularly dismal.

For the third year in a row, Kyrgyzstan was given “not free” country status by the international NGO Freedom House in its annual Freedom in the World report. On the V-Dem Institute’s Liberal Democracy Index, it received the lowest score in a dozen years. For roughly the same period, the latest Bertelsmann Transformation Index report shows the country’s lowest scores regarding the rights to peaceful assembly, freedom of expression, and civil liberties in general. In 2023, Kyrgyzstan fell 50 places to 122 in the World Press Freedom Index by Reporters Without Borders, down from 72.

How did Kyrgyzstan get to this point and what currently determines the dynamics of the human rights situation? These questions can be answered both from a long-term perspective — through the way the political environment for the exercise of human rights has been shaped — as well as by more closely examining the last three years, when the current drastic backslide began.

An “Island of Democracy” Submerged

In its first years of independence, Kyrgyzstan ratified key international documents — in 1994, the international treaties on civil and political rights, and on economic, social, and cultural rights, as well as the convention on the rights of the child. In 1997, it ratified the conventions on combating racial discrimination, discrimination against women, and torture. One of the last documents to be ratified in 2019 was the convention on the rights of people with disabilities.

Acquiring its image as a country that was quite free took place against the backdrop of the initial liberalization of the early 1990s, which promoted democratization and respect for human rights. However, this was interrupted by the authoritarian tendencies of the first presidents — ultimately, the country’s first two leaders had to flee popular uprisings in 2005 and 2010. After a brief return to democratization, there was a renewed decline. The most recent efforts to consolidate rights and freedoms, with the adoption in 2010 of a constitution that would de-monopolize power, were ultimately unsuccessful due to the events of three years ago.

For most of the post-Soviet period, the country was called an “island of democracy” not only because of its rights and freedoms, which were generally not at such a low level in its first decades of independence, but also in comparison with neighbouring, rather more authoritarian countries. While most other Central Asian countries have only changed president once, and even then in most cases due to the natural death of unremovable predecessors, Kyrgyzstan now has its sixth president.

Threats and more targeted crackdowns on journalists, bloggers, and activists have intensified in recent years.

The country appears to have gone through multiple shifts where yesterday’s political prisoners came to power, while media and civil activists gained more freedom and, according to this, the pursuit of freedom and respect for rights should have stabilized. However, over the last three years there has been a backlash against rights and freedoms.

The Backslide

The current situation began to take shape in October 2020. At that time, a political crisis occurred due to protests over the results of parliamentary elections that were not recognized. After the president resigned, the current leadership of the country came to power. The current backslide since then has occurred in two forms — through selective and targeted attacks on those who criticize the actions of the authorities, and through more systematic changes that shrink the political space for critical voices.

The last three years have been characterized by targeted and occasionally mass repression of activists and the media, as well as by systematic changes in the regulatory environment that shrink civic space.

Targeted repression is a common tactic of authoritarian regimes to eliminate an immediate threat while simultaneously intimidating others who are dissatisfied with the government. Threats and more targeted crackdowns on journalists, bloggers, and activists have intensified in recent years. Newspaper websites have been blocked, media outlets closed, criminal cases have been opened against journalists, their homes and offices searched, and bloggers summoned to law enforcement agencies for their social media posts.

More recently, bloggers have also been arrested and made to stand trial for such posts, on multiple occasions. One of the unprecedented attacks was the closing, albeit temporary, of Radio Azattyk (the national bureau of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty) in 2022. Another instance of freedom of expression coming under pressure was when the office of the independent investigative journalist Bolot Temirov was searched by police on suspicion of drug possession. Shortly before, Temirov and his team had published an investigation into corruption allegedly involving family members of the head of the State Committee for National Security (UKMK), Kamchybek Tashiev. Although Temirov was acquitted, he was soon expelled from the country following a court decision in another case.

At a certain point, selective prosecution in one case turned into a broad crackdown on activists and opposition politicians. In the autumn of 2022, during negotiations regarding the Kyrgyz–Uzbek border, the lands of the Kempir–Abad reservoir were transferred to Uzbekistan, which caused discontent among local residents. A number of activists and politicians formed a committee to protect the reservoir — their arrests began just a day after its creation.

Since October 2022, almost 30 people have been held on charges of inciting mass riots. The case, which has been classified for over a year, has yet to go to trial and, although a number of the defendants have been released under house arrest, many are still in detention pending the investigation.

Shrinking Civic Spaces

All these events took place and continue to take place against the backdrop of systematic changes to strengthen authoritarian rule in Kyrgyzstan. The first and main step in this direction was a radical change to the constitution, adopted by referendum in April 2021. The main amendments were that the president would now preside over and give instructions to the cabinet, and in addition, the chairman of the cabinet would also be the head of the presidential administration. The presidential term was shortened from six to five years, but the president can be elected twice (previously he could be elected once).

The new constitution strengthened the president’s individual power, but discussion of this process was far from transparent. The highly respected Venice Commission questioned the legitimacy of the process, stating that it was conducted too quickly and did not allow for a thorough discussion of the draft constitution. Following these constitutional changes, a large number of laws began to be changed to bring them in line with the new document. Many of these changes, due to the strict centralization of power, affected the rights of the country’s citizens.

The crackdown on dissidents and the institutionalization of the government’s dramatically increased powers allowed it to quickly build a political regime that ignored human rights.

The amendments to the constitution have strengthened the president’s powers in appointing judges. One of the rare positive steps (noted, in fact, in the Venice Commission’s opinion) to re-establish the Constitutional Court as a separate body was reversed by a recent draft law giving not only the head of the court the ability to review its decisions, but also the president. Among the justifications that can be used to call for a review is if a judgement contradicts “moral and ethical values and public conscience”.

The draft law was put forward immediately after the head of the UKMK, Tashiev, publicly criticized the Constitutional Court’s decision on the possibility to change a patronymic to a matronymic upon reaching adulthood. [1] This led to the initiation and rapid adoption of a law stipulating that decisions by the Constitutional Court can be reviewed on the recommendation of the court’s head or the president on a number of grounds, including if the decision “contradicts moral and ethical values and public conscience of the people of the Kyrgyz Republic”. Under this law, the Constitutional Court reviewed and overturned its own decision.

Many previous institutional gains, which represent years of negotiations and the combined efforts of many people, are now being rolled back to their starting positions. This was the case with local self-governance, the reforms to which were effectively wiped out due to the rigidly vertical power structure that has also been enshrined in the constitution. Attempts to close the National Center on Prevention of Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment in 2022 and assign it to the office of the Ombudsman are in the same vein.

Sporadically applied temporary bans on peaceful marches and demonstrations in the centre of the capital are now gradually becoming permanent. In March 2022, a temporary ban on protests on the central square in front of government buildings was extended by a court ruling and expanded to the Russian Embassy building and other locations in the centre of Bishkek. In December 2023, a planned motorcade to protest against the change to the state flag (which had been initiated by a number of deputies and supported by the president) was banned.

In the summer of this year, a settlement was reached in the case mentioned above between the Ministry of Culture and Azattyk. This case revealed a new method of placing pressure on journalists, which systematizes ways of putting pressure on free speech in a new form. While previously the prosecutor’s office and other law enforcement agencies pursued media cases to protect the honour and dignity of the president, as was the case with Atambayev’s widespread lawsuits against journalists in 2017, the use of a non-law enforcement state agency to systematically exert pressure on free speech is a new phenomenon, and apparently one that is gradually intensifying. Recently, the Ministry of Culture has not only filed complaints against media outlets but has also attempted to shut down TikTok and issued warnings to media outlets regarding their publications.

Windows of Opportunity

There are, of course, key driving forces and accompanying factors that contextualize the deterioration of rights in Kyrgyzstan. In general, a decline in human rights can be observed around the world. Many reports have the expression “democratic backsliding” in their title and the drivers of increasing authoritarianism are similar across different national contexts. Three aspects can be focused on that are most pronounced in Kyrgyzstan — a window of opportunity that is favourable to anti-democratic forces, conservative populism, and the weakened international order.

In October 2020, there was a window of opportunity that the current group of people in power took advantage of, before firmly closing it so that others would not take advantage of it. The situation at that time corresponded to the classic description of the political opportunity structure — open access to political processes for different actors, instability of usual political alliances, and intra-elite conflicts, arising from the post-election protests in 2020. Unlike the political upheavals in 2005 and 2010, three years ago the current government did not face any serious opposition and every effort was made to ensure that an opposition did not subsequently emerge.

In the absence of clear and serious opposition, the authorities were able to quickly consolidate their control of various resources and strengthen their powers through a hastily implemented constitutional reform. The crackdown on dissidents and the institutionalization of the government’s dramatically increased powers allowed it to quickly build a political regime that ignored human rights.

In Kyrgyzstan, populism plays a significant role in the formation of the current regime. It reflects to a certain extent the real public support for the current government — although opinion polls indicate that this support is declining over time — while at the same time it is also a deliberately fostered by the authorities to legitimize themselves.

There is democratic backsliding in many countries and, although there is no sign of the government directly borrowing from this, it clearly serves to justify the backsliding that is taking place in Kyrgyzstan.

For example, according to the 2023 UNDP report on the Gender Social Norms Index, Kyrgyzstan was among the five countries with the largest backslide (according to two waves of the World Values Survey from 2010–2014 and 2017–2020). In recent years, the close association of politicians and civil servants with conservative groups has become more pronounced. Examples include the censorship by the Ministry of Culture of the contemporary feminist art exhibition Femminale in late 2019 under pressure from conservative groups, or the arrest of the organizers of a peaceful march on 8 March 2020 when the demonstration was attacked by groups of conservative activists.

Conservatism is also layered on top of radical public sentiment and the expectation of a more authoritarian government. More than a third of respondents from Kyrgyzstan in the World Values Survey in early 2022 responded positively to the statement that “the entire way our society is organized must be radically changed by revolutionary action”, and almost two-thirds responded positively to “greater respect for authority”.

The conservatism in the politics of the current government has been clear from the very beginning. One of the first decrees after Sadyr Japarov was elected president was a decree on “spiritual and moral development” in January 2021. Similar provisions were introduced the same year as part of the constitutional reform.

In general, there is democratic backsliding in many countries and, although there is no sign of the government directly borrowing from this, it clearly serves to justify the backsliding that is taking place in Kyrgyzstan. There is, of course, also the effect of the war in Ukraine, which has called into question not only the norms of international humanitarian law and the rules of warfare, but the question of respect for rights in general.

In this context, it is also important to coordinate efforts to build a common human rights agenda with foreign actors. The importance and role of Western and international actors is declining. Due to poor economic management, Kyrgyzstan has been borrowing extensively from foreign donors for many years. At the beginning of 2023, its external debt amounted to 4.4 billion US dollars, of which almost 1.8 billion were owed to the Export-Import Bank of China. This reflects the changed situation over the last decade and a half, where the Kyrgyz government has begun to find donors who lend money without attaching political conditions such as improving the human rights situation, for example. In addition, much of the money previously allocated by Western donors was used to fund the budget and large infrastructure projects, rather than the development of modern political institutions that protect human rights.

Could Kyrgyzstan Bounce Back?

Is it possible for new democracies in decline to bounce back from the bottom? Occasionally it happens, and a report by the V-Dem Institute from 2023 shows that key elements in such cases are popular mobilization against the incumbent government, the judiciary’s opposition to the authoritarianism of the executive branch, an alliance of the political opposition with civil society, critical triggering events such as elections, and international democratic support.

None of these can currently be observed in Kyrgyzstan — there is no independent judiciary or political opposition, the public is not critical of the current government, and most international actors are chiefly preoccupied by the war in Ukraine. However, the country’s modern history shows that authoritarian tendencies can be replaced by instances of democratization.

The human rights situation around the world is far from positive. In Kyrgyzstan too, given the circumstances described here, the situation is rather problematic. Examples of other countries and Kyrgyzstan’s own experience suggest that it is possible to “bounce back from the bottom”, but many of the factors necessary for this are currently missing. Besides, there are many more examples from around the world of a gradual yet inexorable slide into authoritarianism.

Kyrgyzstan unfortunately appears to be at the beginning of such a slide and the key criteria for a possible bounce-back may not emerge soon. This makes the task of protecting human rights in the country not so much a matter of committing to their further advancement as to the preservation of what has already been achieved.

In the anniversary year of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, it will be a considerable achievement if it is possible not so much to bounce back, but rather to slow the uncontrollable downward slide.

Translated by Charlotte Bull and Samuel Langer for Gegensatz Translation Collective.

[1] For more than two years, the children’s writer and activist Altyn Kapalova fought in the courts to allow her children to take a matronymic, a name derived from the mother’s first name, as opposed to a patronymic, derived from the father’s first name. The Constitutional Court finally ruled in the summer of 2023 that upon reaching adult age, a child has the right to choose between a patronymic and a matronymic. In addition to Kamchybek Tashiev, the mufti of Kyrgyzstan also criticized the court’s decision.